Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five – The Message from the album ‘The Message’ (1982)

When No One Would Listen, This Exoneree Spoke Through Hip Hop

Huwe Burton was wrongly incarcerated, and as a teen from the Bronx, turned to music to express himself.

Special Feature 02.23.22 By Daniele Selby

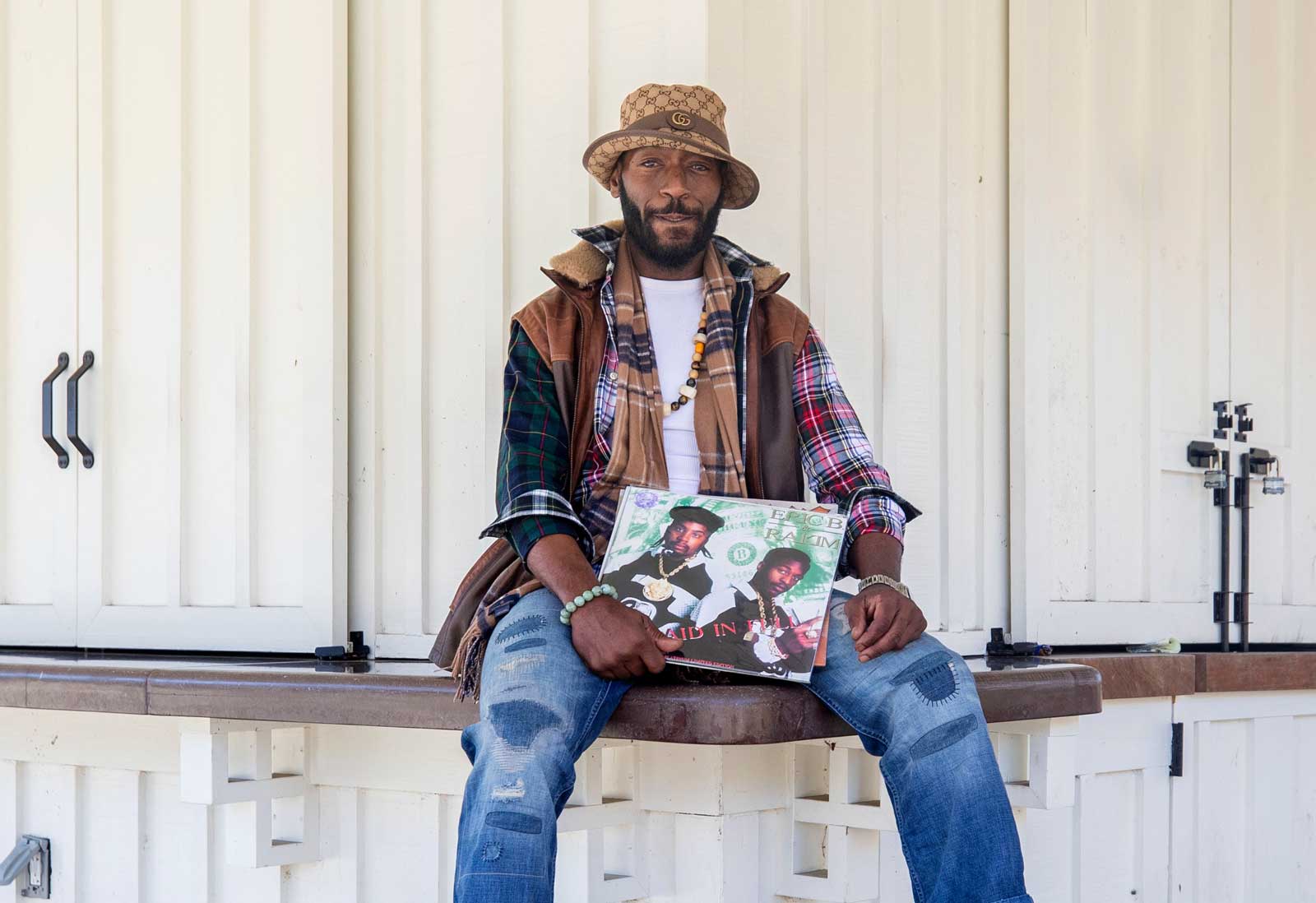

“I think it’s a disrespect to piano players everywhere to call myself a pianist. It really is. I’m simply a student of hip hop — not any of those other things,” said Huwe Burton.

Mr. Burton’s father played the saxophone, so their house was always filled with music, but it wasn’t until Mr. Burton started hearing hip hop that he knew he wanted to make music himself.“Until rap, there was no form of music that spoke directly to what we were seeing, what we were feeling, and experiencing,” said Mr. Burton, who is from the Bronx, which is widely considered the birthplace of hip hop. What initially drew Mr. Burton to hip hop was the genre’s unique lyricism, its capacity for storytelling, and the way it grew out of nothing and yet managed to capture his experience and his community.

“‘The Message’ — [by hip hop pioneers] Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five — painted such a clear picture of New York City, the Bronx in particular. It was so graphic, so detailed, and each of them in their verses took you on like this journey and walked you through their area of the neighborhood, and it was so on point,” he said, recalling the first song that really grabbed his attention.

He calls rappers Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, KRS-One, and Kool G Rap his “Mount Rushmore of hip hop.”

Hip hop music and culture emerged from block parties in New York City, where Mr. Burton recalled people would tap power from street lamps to light up an abandoned building for a party. And what he remembers most about those parties was the sense of community and resilience.

“So much had been taken from them [as a community]. Through music, they still pressed on through the poverty they experienced, they still said, ‘We’re going to have this party, we’re going to promote this music, we’re going to make money from it,’” he explained. “Same thing with me — with everything that was taken away from me, music assisted me, helped me move forward, and try to keep myself in a good headspace to have the strength to continue to fight.”

“Music assisted me, helped me move forward, and try to keep myself in a good headspace to have the strength to continue to fight.”

“Music assisted me, helped me move forward, and try to keep myself in a good headspace to have the strength to continue to fight.”

Huwe Burton

Huwe Burton on Feb. 5, 2022, at Hampton Park in Charleston, South Carolina. (Image: Gavin McIntyre/Innocence Project)

Racial bias, deception, and a wrongful conviction

In January 1989, Mr. Burton, then 16, came home to discover that his mother had been killed. Detectives interrogated him alone, threatening to pile additional charges on and then offering leniency if he confessed to killing his mother. The use of these deceptive tactics in interrogations remains legal in New York, and most of the United States today. Only Illinois and Oregon have banned the use of these tactics specifically when interrogating minors.

Following several hours of coercion and deception, the shocked and exhausted teenager provided a written and recorded confession that fit with detectives’ theory of the crime. The teen said he had accidentally killed his mother after she refused to give him money to pay a drug debt — despite having no history of drug use and no criminal record. And he told detectives that he’d given his mother’s car, which was missing, to the drug dealer as payment.

As soon as he was out of police custody, Mr. Burton recanted his statement. At trial, he testified that the officers had coerced him into falsely confessing. False confessions are a leading cause of wrongful conviction, and youths are particularly vulnerable to falsely confessing when deceptive tactics are used. His attorney attempted to call a psychiatrist to testify about the unreliability of his confession, but the court denied the request. Mr. Burton was wrongly convicted in 1991 — just one year after five Black and Brown teenagers from Harlem, known as the Central Park Five, were wrongly convicted based on coerced false confessions.

Mr. Burton was later sentenced to 15 years to life in prison. At the time, he was just 19 years old.

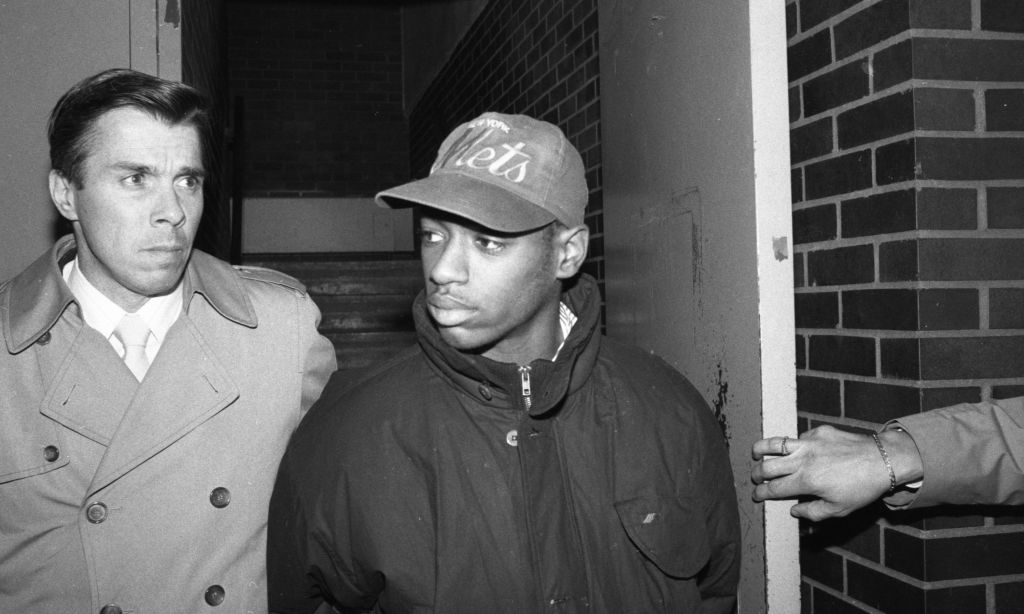

Huwe Burton, charged with killing his mother, was taken from the Laconia Avenue precinct. (Image: Clarence Davis/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

Reflecting on his wrongful incarceration, Mr. Burton said detectives made assumptions about him and his family based on his race just as they had in the case of the Central Park Five. Mr. Burton’s mother was a registered nurse, his father was an independent contractor. Both were homeowners. Mr. Burton himself had no criminal or disciplinary history.

“You take all those factors, but you give me a different ethnicity … they probably would have explored every avenue they could to find out who was responsible for this,” Mr. Burton said. “But because these were Jamaicans, there wasn’t as much value placed on [finding the person who actually committed the crime] There were biases and perceptions, which made them say, ‘We feel we have our man … we’re not going to pursue this further.’”

Both Mr. Burton and the Central Park Five were arrested and wrongly convicted in the era of “stop-and-frisk” practices, the crack epidemic, and the war on drugs. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, such policing approaches led to the racial profiling of many Black and brown New Yorkers. At the same time, the myth of the “superpredator” — the idea that some youths are naturally “amoral” and impulsively violent — became widespread. This myth, rooted in racist beliefs about Black children and communities in particular, led to juveniles being sentenced as adults and given excessively harsh sentences, including life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.