Thurgood Marshall’s Pursuit of Justice Lives on at the Innocence Project

Before becoming the first Black Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall represented innocent Black men.

02.25.21 By Christina Swarns

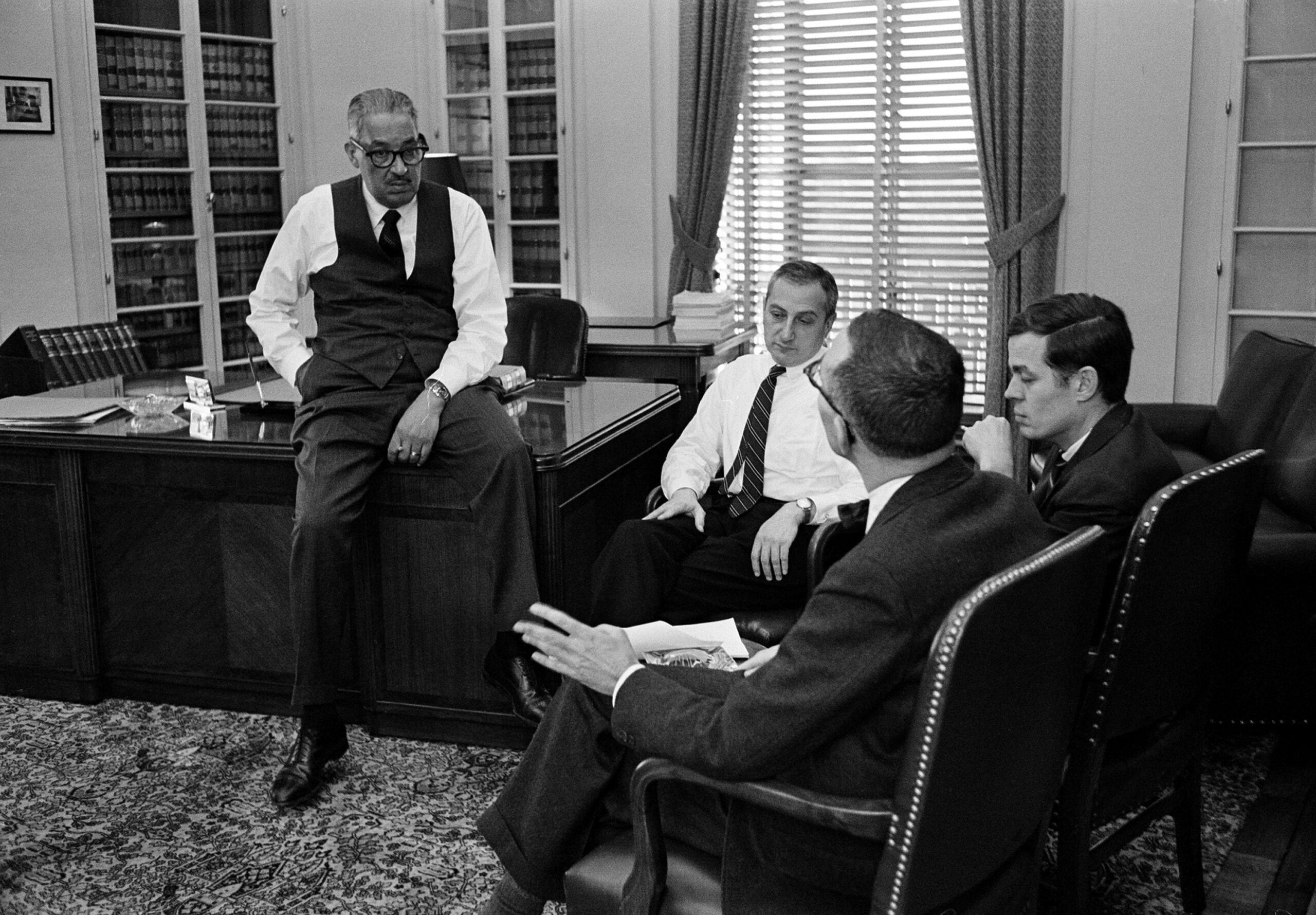

This Black History Month, I find myself reflecting on the connections between the work of the Innocence Project and the work of attorneys at the forefront of the civil rights movement, like Thurgood Marshall. Before he became the first Black justice of the Supreme Court, and before he argued — and won — Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark decision that ended racial segregation in the U.S., Justice Marshall represented innocent Black men charged with and convicted of rape and murder in the Deep South.

At great personal and professional risk, Justice Marshall confronted explicit racism, challenged false confessions, disputed erroneous identifications, exposed police brutality, and condemned prosecutorial misconduct on behalf of such innocents as the Groveland Four. The injustices he observed and experienced forever informed his understanding of the fairness of the criminal legal system.

Sadly, many of the Innocence Project’s exoneration cases echo the issues litigated by Justice Marshall almost a century ago. We, too, challenge eyewitness misidentification, police and prosecutor misconduct, coerced confessions, and, of course, racial bias and discrimination in the administration of criminal justice.

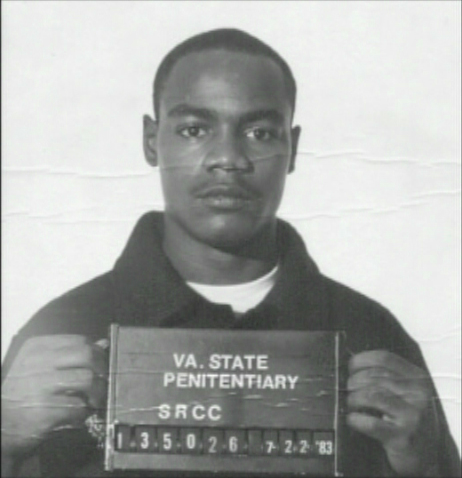

Just look at the case of Innocence Project Board Member Marvin Anderson, who spent 15 years in prison for sexual assault in Virginia — a crime he did not commit. The victim, a white woman, told police that her attacker had said that he’d been with a white woman before. The police officer knew of only one Black man who fit that description and on that basis alone, Mr. Anderson was arrested and charged.

Tried by an all-white jury that deliberated for just a couple of hours, Mr. Anderson was sentenced to 200 years in prison despite having solid alibi witnesses and no criminal record. It was only after the Innocence Project was able to locate and test DNA evidence that Mr. Anderson was able to prove his innocence and fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a firefighter. In fact, he retired as the EMS Volunteer fire chief in Hanover County, Virginia, in 2019.

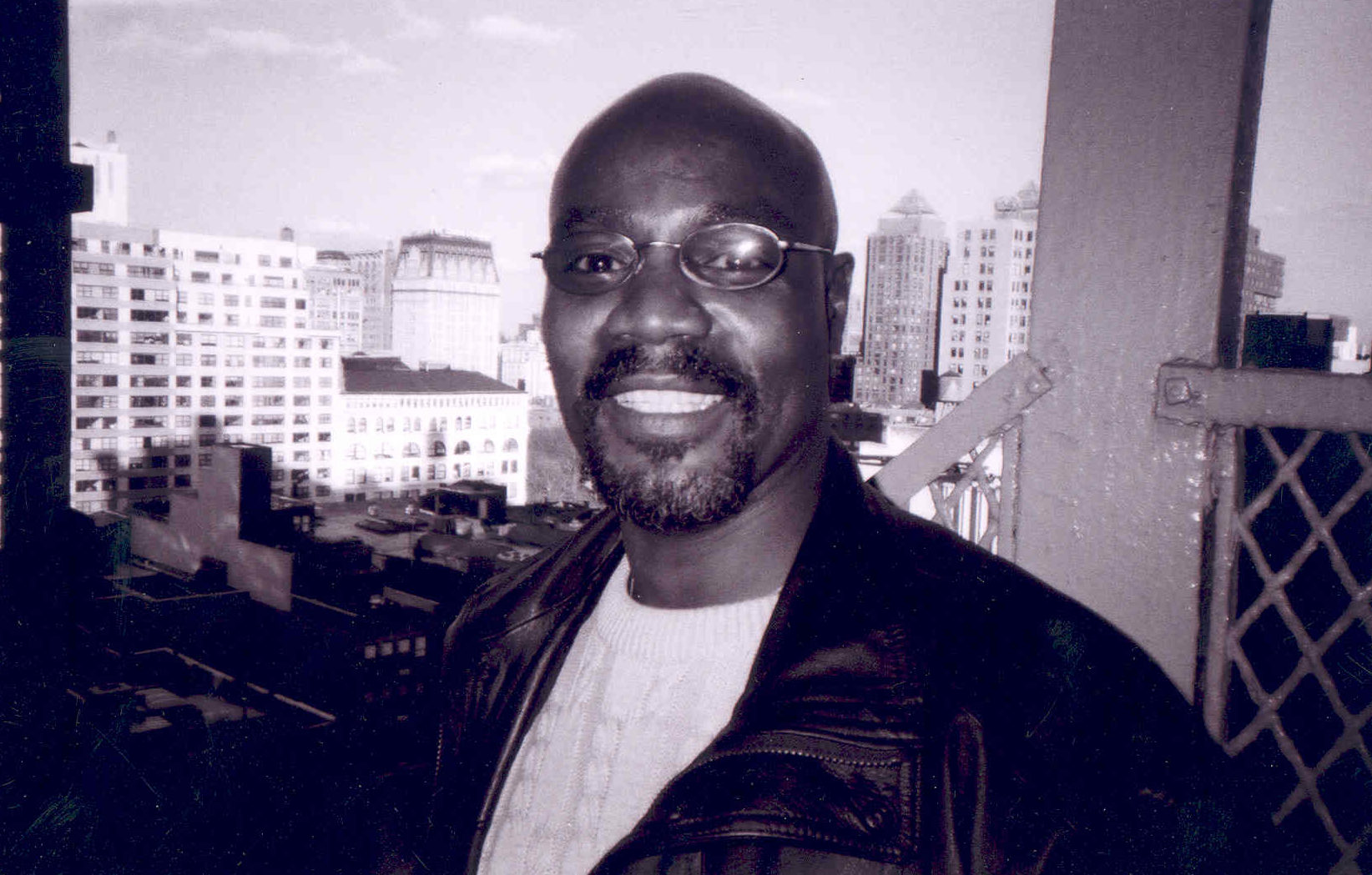

And then there’s Calvin Johnson — our very first exoneree board member — who was tried for two sexual assaults in Georgia in the 1980s. In one case in Clayton County, Mr. Johnson and his attorney were the only Black people in the courtroom. The judge, prosecutor, clerk, stenographer, jury foreman, and the entire jury, were white. Two Black jurors who were initially placed in the pool were stricken by the prosecution without explanation. The all-white jury rejected the alibi testimony offered by the four Black witnesses and deliberated for just 45 minutes before returning with a guilty verdict. Mr. Johnson was sentenced to life in prison in November 1983.

Seven months later, he was tried for a different case in Fulton County. This case against him was stronger because Mr. Johnson was cross examined on his recent rape conviction in Clayton County and yet he was acquitted. There was one notable difference at the second trial: the composition of the jury. A jury of five white and seven Black people unanimously questioned the reliability of the cross racial identification. The second jury evidently found the alibi testimony of Mr. Johnson’s mother and father more credible.

More than a decade after his conviction, DNA testing of the rape kit secured by the Innocence Project concluded that Mr. Johnson was not the perpetrator. In 1999, the district attorney declined to retry the case and Calvin walked free after 16 years of wrongful conviction.

These are just two cases that show how the Innocence Project stands on the shoulders of brave civil rights giants like Justice Marshall. We share his belief that “America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better.” And we are committed to building on his legacy by working every day to make the criminal legal system better, more accountable, more fair, and more just at every level.

I encourage you to learn more about the heroes of the civil rights movement and the ongoing struggle for justice. Read powerful quotes from some civil rights leaders in our feature here. You can pick up one of the outstanding books on this reading list, which includes Gilbert King’s Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the Groveland Four case, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys and the Dawn of a New America. And, finally, you can check out the amazing Netflix series, The Innocence Files, that profiles egregious cases of racial bias and wrongful conviction, telling the stories of eight men who lost years of their lives because the system failed them.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

March 4, 2021 at 9:01 am

February 28, 2021 at 1:31 am

Thank you for your service.

I have always admired the hard work that everyone does in these cases. I have been following cases for years. I believe with my whole heart and soul and mind that these people need a true chance at honesty and justice. And I will be privileged and honored to help with this in any way shape or form that I could be beneficial. This is my dream to do