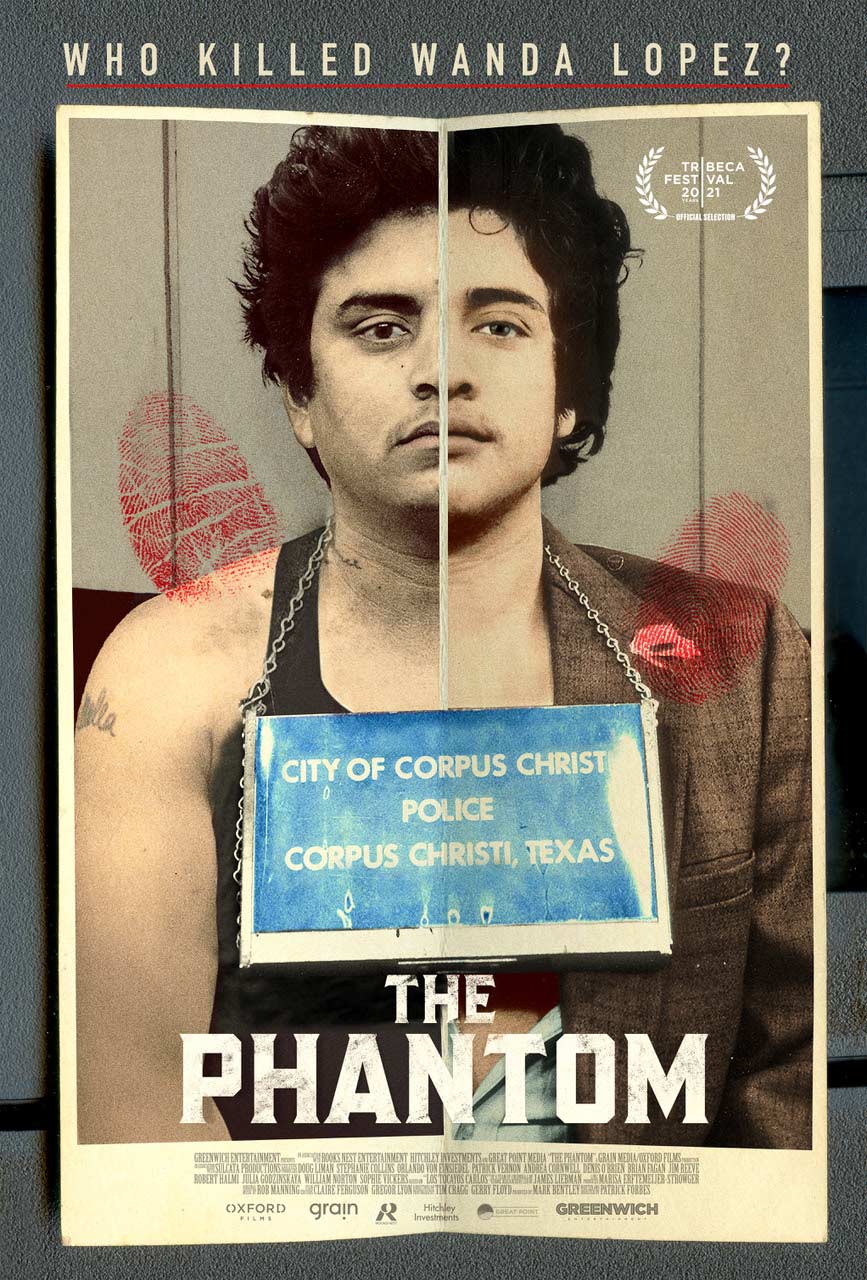

‘The Phantom’: The Unjust Execution of Carlos DeLuna

In 1989, Carlos DeLuna was executed for the murder of a gas station employee. Yet, evidence uncovered by a Columbia law professor and his team pointed to another suspect.

Special Feature 06.11.21 By Justin Chan

The Phantom will release nationally on July 2.

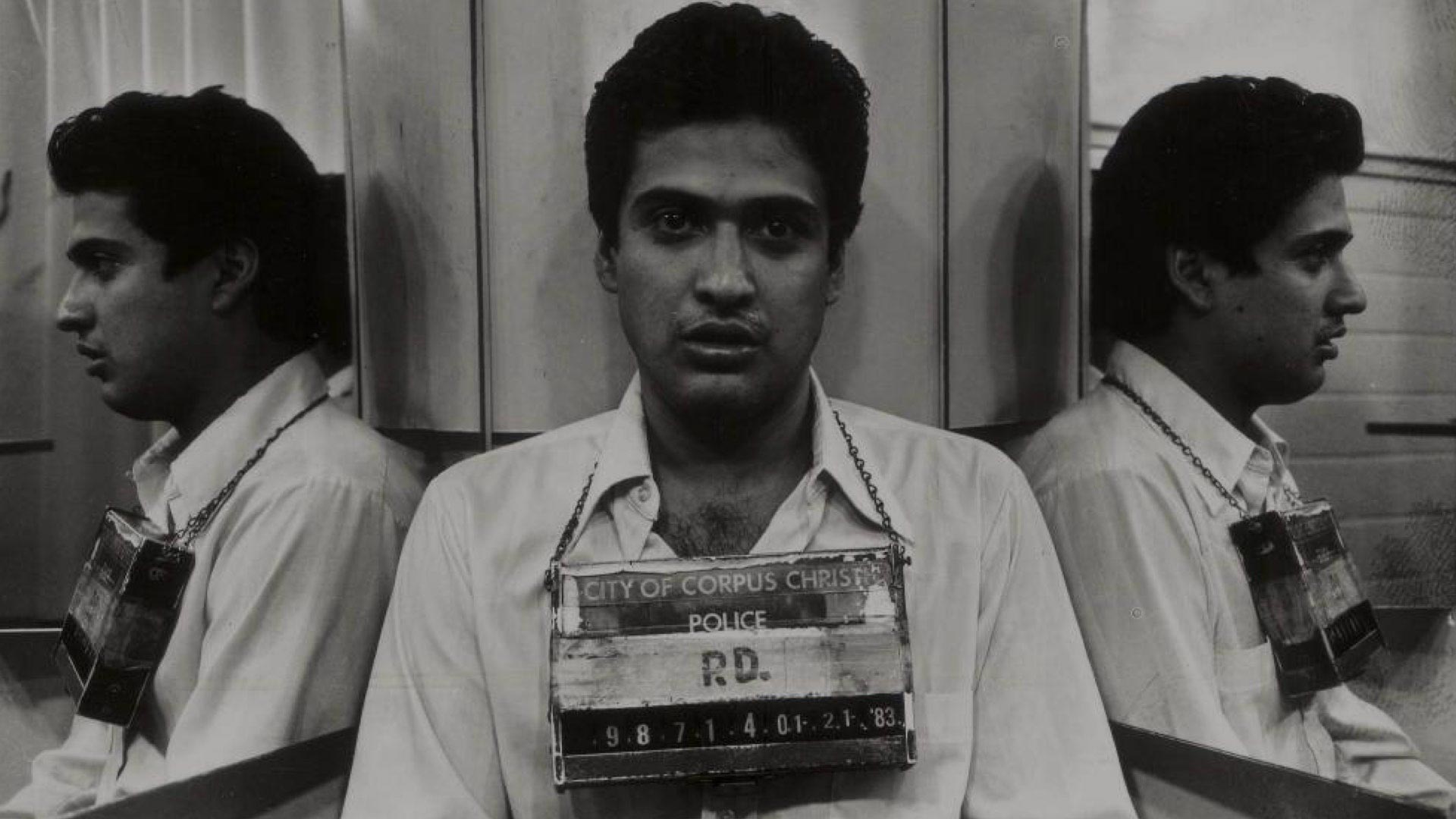

On Dec. 7, 1989, Carlos DeLuna, a young Latino man, was executed for the 1983 murder of Wanda Lopez, an employee at a gas station in Corpus Christi, Texas, despite maintaining his innocence. He was just 27 years old.

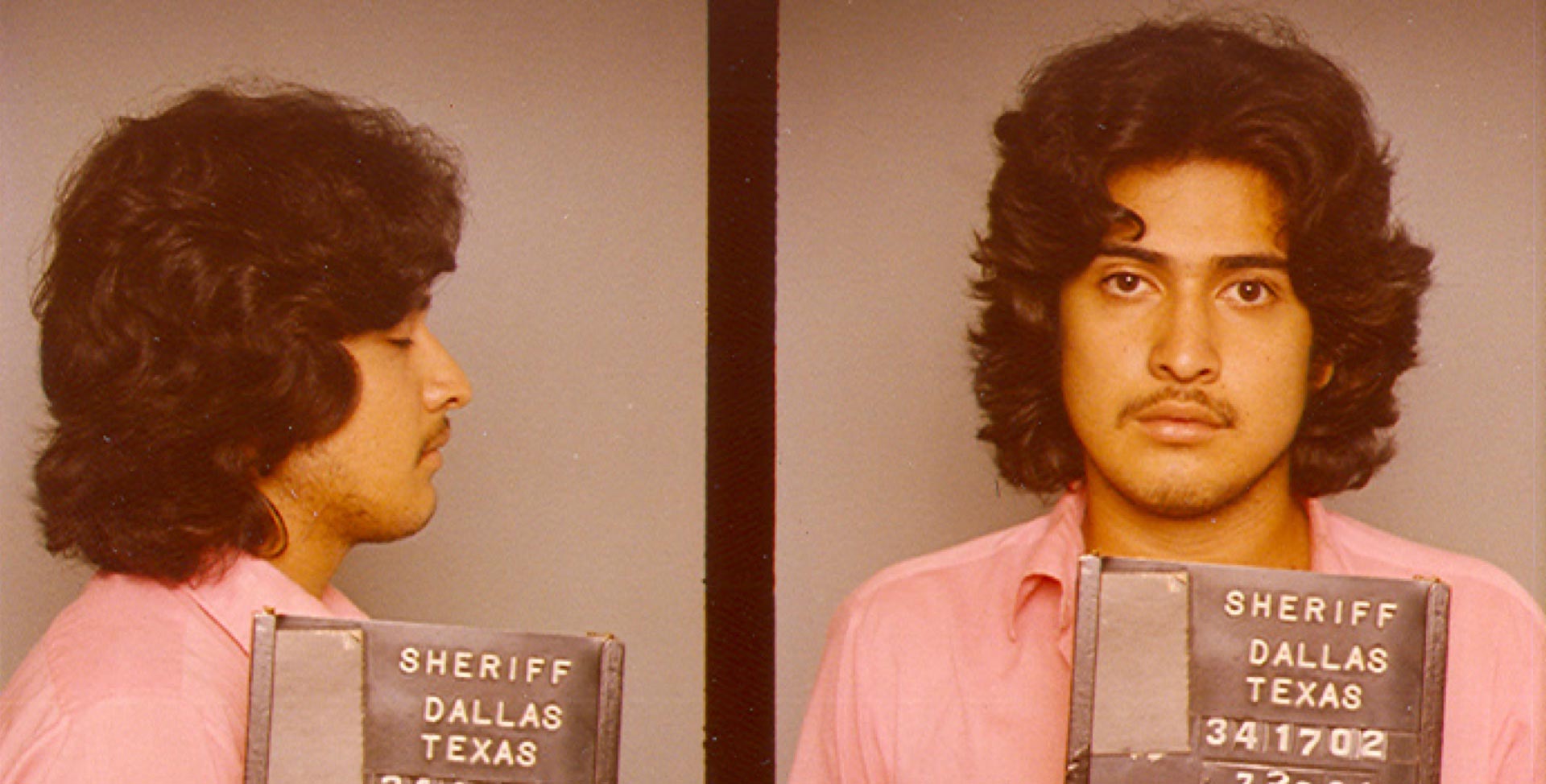

At his trial, prosecutors dismissed Mr. DeLuna’s claim of an alternate suspect — Carlos Hernandez, whom he insisted had committed the murder — asserting that “Mr. Hernandez” was a “phantom” suspect whom Mr. DeLuna had fabricated. Mr. DeLuna was later convicted and sentenced to death largely based on eyewitness misidentification.

The prosecution’s description of Mr. Hernandez is now the title of a deeply disturbing documentary, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival on June 14 and is set for release on Netflix on Sept. 30.

The Phantom draws from a series of interviews — including those with Mr. DeLuna’s siblings, his trial attorney, prosecutors, and eyewitnesses — casting tremendous doubt on Mr. DeLuna’s conviction and revealing new, disturbing evidence that points to his innocence. It follows a re-investigation into Mr. DeLuna’s claim about Mr. Hernandez by Columbia law professor Jim Liebman and his team, who later documented their comprehensive findings in a book titled The Wrong Carlos, an article in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review, and online.

The documentary presents a damning portrait of the United States’ criminal legal system, which has heavily disadvantaged both members of the Latinx community and people living in poverty. Mr. DeLuna was one of three children raised by a single mother in a low-income neighborhood of Corpus Christi, where killings and fistfights were common and where poor residents were too readily charged with capital murder, convicted, and sentenced to death with little, if any, legal representation. The Phantom also highlights the sloppiness of the investigation, including law enforcement’s failure to look into plausible alternative suspects and the unreliability of eyewitness identification.

In truth, Mr. DeLuna’s case was one that had all the telltale signs of so many wrongful convictions.

Wanda Lopez was a 24-year-old single mother who worked at a Sigmor Shamrock gas station.

The case of Carlos DeLuna

On the night of Feb. 4, 1983, Ms. Lopez, a 24-year-old employee at a Sigmor Shamrock gas station, called police to report a suspicious individual with a knife. While on the phone with a 911 dispatcher, Ms. Lopez attempted to give the individual — whom she described as Hispanic — money in an effort to get him to leave the station’s convenience store. Seventy-seven seconds into the call, she let out a scream.

Law enforcement arrived at the scene shortly after to find a witness tending to Ms. Lopez, who had been stabbed twice. The witness described Ms. Lopez’s attacker to an officer as a mustachioed Hispanic man in a flannel jacket and a grey sweatshirt. As police began their manhunt for a suspect matching this description, a couple nearby told the same officer that they had seen a man in a different outfit running about two blocks away from the gas station. The second description was shared with other authorities as that of a second possible suspect.

Amid a chaotic manhunt for the two men described by witnesses, police received multiple calls from neighborhood residents about a man hiding underneath a pickup truck. Police followed the tip and found Mr. DeLuna, whom eyewitnesses later identified as Ms. Lopez’s murderer during a highly suggestive identification procedure.

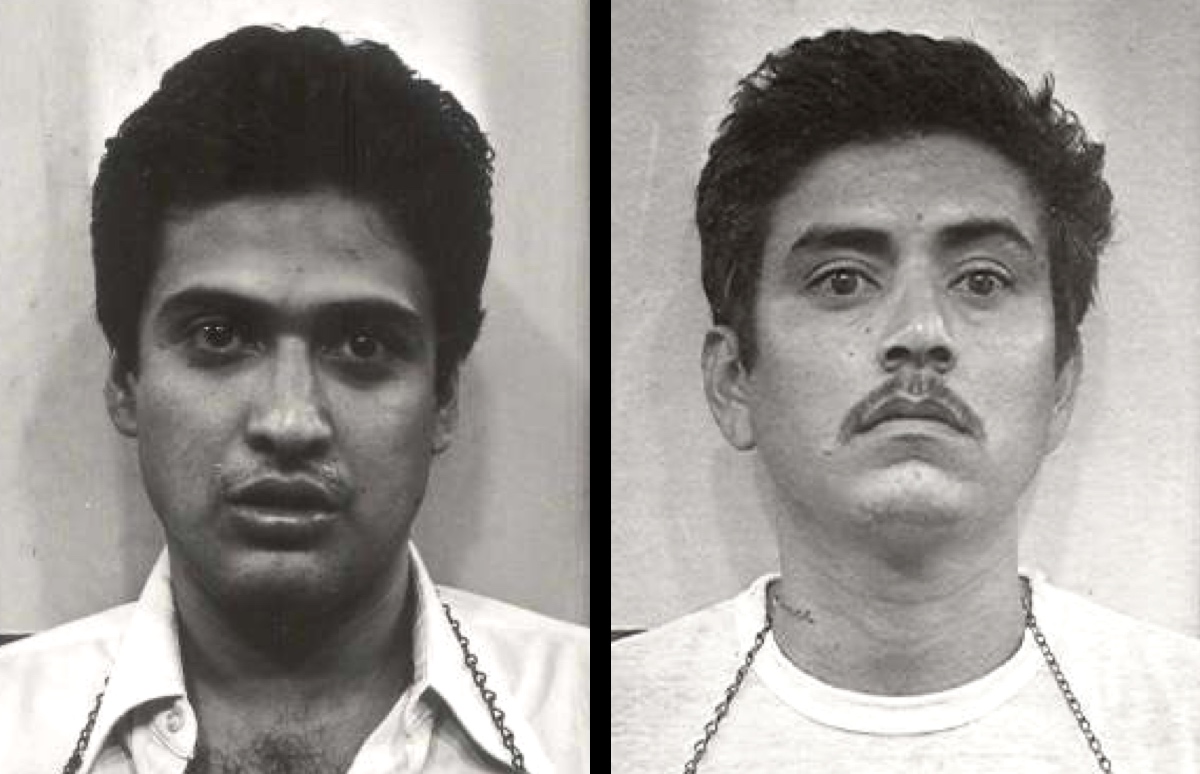

At his trial, Carlos DeLuna (left) maintained that Carlos Hernandez (right) had committed the murder, but the prosecution and courts asserted that Mr. Hernandez was a “phantom” person.

At his trial in July 1983, Mr. DeLuna insisted that Ms. Lopez had been murdered by his acquaintance, Carlos Hernandez. But prosecutors rejected Mr. DeLuna’s claim without conducting a thorough search for Mr. Hernandez. Instead, they accused Mr. DeLuna of blaming the murder on a “phantom” person. The jury eventually sided with the prosecution, convicted Mr. DeLuna, and sentenced him to death. Despite Mr. DeLuna’s subsequent appeals, the courts upheld his conviction and death sentence, essentially reaffirming that Mr. Hernandez did not exist. In 1989, Mr. DeLuna died by lethal injection.

Evidence uncovered years after Mr. DeLuna’s execution reveals not only that Mr. Hernandez existed, but that he was well-known to police and prosecutors at the time of trial.

The Phantom argues that, for Mr. DeLuna, this was the ultimate miscarriage of justice.

“All these poor people, they were all getting found guilty, they were all going to death row, and nobody represented them.”

“All these poor people, they were all getting found guilty, they were all going to death row, and nobody represented them.”

Rene Rodriguez Attorney for Wanda Lopez's family

Claude Jones (left) was convicted of murder on a single piece of evidence that did not belong to him.

Wrongful conviction and the death penalty

Data has shown that there is a real risk of executing people who are innocent in the United States.

Since 1973,185 people who have been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in the U.S. have been exonerated, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, including Innocence Project clients Clemente Aguirre, Rolando Cruz, and Alejandro Fernandez. About 60% of those exonerees were either Black or Latinx, underscoring the discriminatory application of the death penalty against Black and brown people. At least two of the exonerees were Spanish speakers with a limited understanding of English that made it difficult for them to adequately defend themselves in court. Others had limited access to adequate resources and quality representation.

And like Mr. DeLuna, some Innocence Project clients have been executed without a fair chance to prove their innocence.

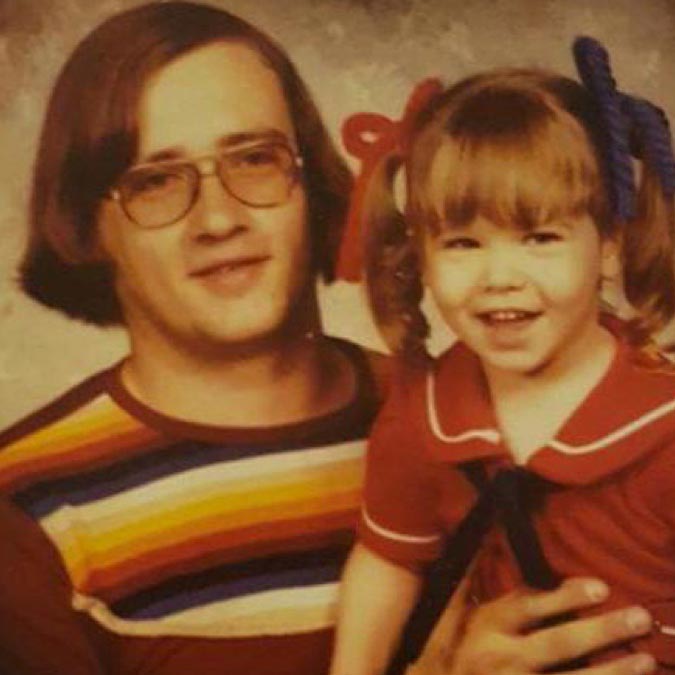

In 2000, Claude Jones was executed in Texas for the 1989 murder of liquor store owner Allen Hilzendager. Mr. Jones’ conviction largely rested on a single piece of evidence — a strand of hair — that was found on the counter near Mr. Hilzendager’s body. Mr. Jones’ co-defendant also testified against him but later signed an affidavit claiming that he had testified after being threatened with the death penalty. Nearly a decade after Mr. Jones’ execution, DNA testing requested by the Innocence Project revealed that the strand of hair did not belong to Mr. Jones, raising serious doubts about his guilt.

In 2004, Cameron Todd Willingham was executed in Texas after being convicted for the 1991 murders of his three daughters by arson. Mr. Willingham’s conviction was based partly on the testimony of forensic science experts who determined that the fire had been intentionally set. A jailhouse informant had also claimed that Mr. Willingham had confessed to the crime. Following Mr. Willingham’s execution, however, five independent, leading arson experts assembled by the Innocence Project, along with an investigative report by the Chicago Tribune, found that the scientific analysis that had been used in Mr. Willingham’s trial was unreliable. An arson expert hired by the Texas Forensic Science Commission also came to the same conclusion.

Sedley Alley was executed without a chance to prove his innocence through DNA testing.

In another case, Sedley Alley died by lethal injection in Tennessee in 2006. Mr. Alley had been convicted in the 1985 rape and murder of Marine Lance Corporal Suzanne Marie Collins. Mr. Alley initially denied any role in Ms. Collins death, but eventually signed a statement admitting to the murder, which he said was coerced. The details of the statement contradicted aspects of the crime scene and autopsy. Moreover, a witness’ description of the suspect did not match Mr. Alley’s appearance. Mr. Alley was executed just years before the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that the state’s post-conviction DNA statute should have allowed testing on pieces of evidence found at the 1985 crime scene — including a pair of men’s underwear believed to have been worn by the attacker. Had testing been done, Mr. Alley would have had strong proof of his innocence.

185

people exonerated from death row since 1970 (Death Penalty Information Center)

115

people exonerated from death row are Black or Latinx (Death Penalty Information Center)

55%

Black or Latinx people on death row (Death Penalty Information Center)

The fight against capital punishment

The Phantom will be released nationally on July 2, which also marks the 45th anniversary of Gregg v. Georgia, a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in a 7-2 decision, that the imposition of a death sentence does not qualify as “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court asserted that the cautious and judicious use of the death penalty, when employed carefully, may be appropriate in criminal cases where the defendant has been convicted of deliberately killing someone.

Yet, as Mr. DeLuna’s case clearly illustrates, the death penalty, in fact, has been carelessly and unfairly applied. According to 2020 data from the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, approximately 2,600 incarcerated people are currently on death row. More than 55% of those people are Black or Latinx. Furthermore, a report from the Death Penalty Information Center shows that not only are Black people overrepresented on death rows across the U.S., people convicted of killing Black people are less likely than people convicted of killing white people to face the death penalty.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.