A Mistaken Identification Sent Him to Prison for 38 Years, But He Never Gave Up Fighting for Freedom

Malcolm Alexander was sentenced to life in prison for a crime he didn't commit and spent decades trying to get back to his family and sweetheart.

Special Feature 09.17.21 By Daniele Selby

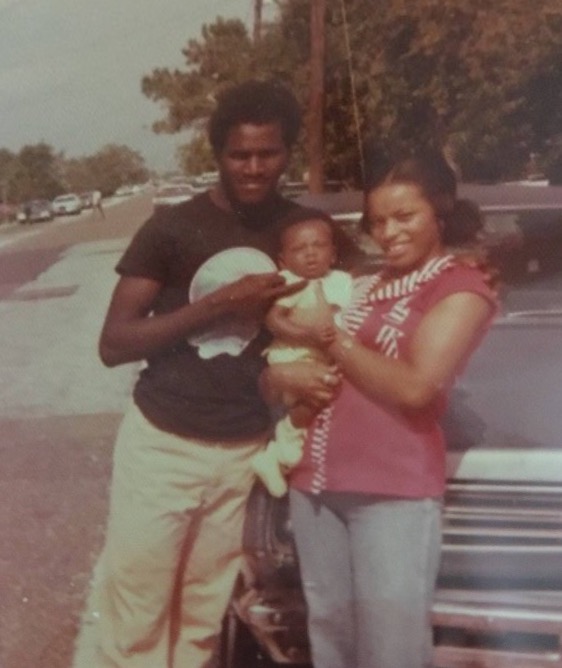

Malcolm Alexander was 20 years old when he was taken from his family and sent to pick cotton in the fields of Angola. Wedged between swampland and the Mississippi River, the place takes its name from the country of Angola, from which most of the people enslaved on the plantation originated.

Only Malcolm had not been taken by slave traders from a home thousands of miles away. He’d been taken from Jefferson Parish, a mere three-hour car ride away, and brought to Angola to work and live out the rest of his life due to an egregious error in the criminal legal system. And the year was not 1780 — when slave ships regularly brought people abducted from Africa to be sold in the South — it was 1980.

On that first morning at Angola, as Malcolm marched to the cotton field in a row of other mostly Black men, bookended by armed men on horseback, he thought, “This is slavery.”

The state of Louisiana, however, calls it prison.

Today, 41 years later, Malcolm is still grappling with the impact of his wrongful conviction and the decades he spent in what many refer to as modern-day slavery.

“I wasn’t supposed to be there.”

Work call at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola prison, was at 7 a.m. At that time, the men had to be ready to board the hootenanny — a large flatbed truck — to be driven to the far end of the farm or lined up with their hoes, ready to keep pace with the “free man” on the horse — as those incarcerated at Angola called the prison guards.

In his first three years at Angola, Malcolm picked cotton and corn, okra and watermelon, then broccoli, cauliflower, and potatoes, depending on the season. He harvested crops from the same land where, 150 years before, slaves had done the same. Back then, the land was known as Angola plantation, not Angola prison.

When there was nothing left to harvest, Malcolm pulled up the cotton stalks and cleared the ditches to prepare the land for the next season, always supervised by “free men” with guns, who rode up and down the fields. Today, about 75% of the people incarcerated there, like Malcolm, are Black, while most of the “free men” on horseback remain white.

“It was like you see in old pictures of slavery,” Malcolm said. “We even had a quota we had to meet at the end of the day,” he added.

A prison officer oversees a work crew heading to the fields at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, on Sept. 6, 2001. (Image: AP Photo/Bill Haber)

During cotton season, prisoners had to fill a 36-by-80-inch sack that sometimes weighed as much as 70 pounds, “if the cotton was dewy that day.” If the sack wasn’t sufficiently full by day’s end, they’d be written up, which meant losing out on weekend privileges like leisure time and access to the law library, or even being sent to solitary confinement.

Rain or shine, heat wave or frost, they worked the fields. Only the injured and the ill were excused.

“I done seen where a horse fell out from the heat, I done seen when a prison guard have to get off the horse to get in the shade of the horse, I done seen other prisoners fell out from heat exhaustion,” Malcolm recalled. “Other times, it would be so cold, you’d have to put on so many pairs of socks and you’d be looking for work to do to stay warm.”

Angola grows approximately 4 million pounds of crops annually, which are sold on the open market, used to feed people incarcerated there, and given to the livestock raised on the prison’s grounds. Over his three years in the fields, Malcolm personally harvested and moved thousands of pounds of cotton and produce, but only ever received a maximum of 4 cents an hour — 25 times less than he’d been paid to pick okra and cut grass in the summer as a kid in Jefferson Parish.

“I just thought, ‘What a mess I’m in,’” Malcolm recalled. “I wasn’t supposed to be there.”

“It was like you see in old pictures of slavery.”

“It was like you see in old pictures of slavery.”

Malcolm Alexander

A mistaken identification and untested rape kit

In November 1979, a white woman was raped at gunpoint in the bathroom of an antique store in Gretna, La. Four months later, police arrested then-20-year-old Malcolm after a white woman with whom he’d had consensual sex asked him for money and then accused him of sexual assault. Malcolm maintained his innocence and after looking into the claim, officials dropped the charges, but the investigating officer presented Malcolm’s photo in a lineup to the rape survivor from Gretna. The woman “tentatively” identified Malcolm as her attacker from the photos.

Three days later, police presented her with a physical lineup that included Malcolm. Malcolm was the only person in the line up who had also been included in the photo lineup. The woman again “tentatively” identified him as her attacker, and the officer who administered the line up documented this only as a possible identification. But after the officer privately interviewed her and took her statement later that day, she said she was 98% sure Malcolm was her attacker.

Research has shown that this practice of repeatedly including a person in an eyewitness identification procedure can “contaminate” a witness’ memory and increase the likelihood that they will identify the individual as the person who committed the crime — even when they’re innocent. More than 60% of people exonerated by DNA were wrongly convicted based on eyewitness misidentifications.

Malcolm insisted on his innocence, but was arrested and charged with rape. The attorney he hired presented a woefully inadequate defense, failing to challenge the identification and missing a court appearance. At Malcolm’s trial, which lasted only one day, the victim testified that there was no question in her mind that Malcolm was her assailant. His defense lawyer did not challenge her testimony, even though the police reports recorded the survivor’s identification as “possible” two times; he did not make an opening statement, call any witnesses for the defense, or adequately cross-examine the State’s witnesses about the identification. The victim’s identification was ultimately the only evidence against Malcolm presented at trial.

Though a rape kit was collected from the victim, basic ABO blood typing which could have shown that Malcolm was not the assailant was not done (DNA testing was not performed because it was not available at the time). And neither the hairs collected from the crime scene, nor the towel the woman had used to clean herself after the attack were tested.

The jury found Malcolm guilty after deliberating for less than an hour, and he was sentenced to life in prison without parole. His lawyer, who promised to file an appeal, never did and was later disbarred following complaints in dozens of cases.

A relentless pursuit of justice

“I ain’t stayed in the fields that long really — three years is a lot out here, but in there, three years is just like standing on your head,” Malcolm said.

Like 70% of people incarcerated at Angola, he had been condemned to spend his life there.

Within his first year at Angola, he earned his GED, going to school half the day and working in the fields the other half. He then applied to change jobs, hoping to learn some new skills. But, his life sentence initially held him back.

“When you have a life sentence, they don’t really look at your character … you didn’t get as many opportunities to go to school and learn something, you’re more subject to work. Everyone could get a GED, but if you wanted to further advance yourself, they looked at the amount of time you had to serve,” Malcolm said.

Malcolm Alexander selling his jewelry at the Angola Prison Rodeo, before he was exonerated, c. 2013. Malcolm handmade both the jewelry and the display shown here. The pink band on Malcolm’s wrist reflects that he is a “trusty,” which indicated his “trustworthiness” and afforded him more freedom and privileges while incarcerated. (Image: Courtesy of Malcolm Alexander)

“But you never know what will happen during a man’s stay there — whether he’s gonna stay there and die there or whether he’s gonna get out. So if a man wants to apply himself and to learn, then he should be afforded that opportunity,” he said.

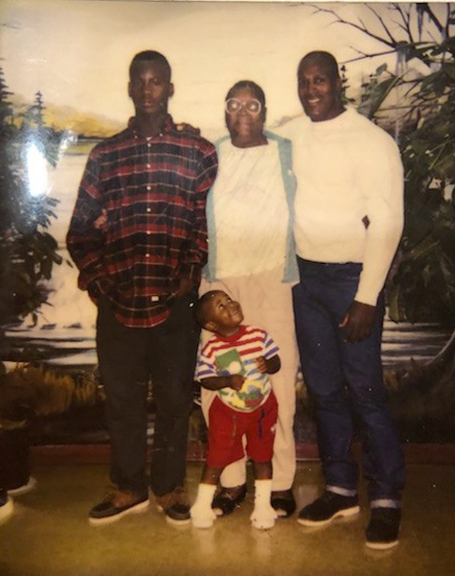

Malcolm made his own opportunities. He did everything in his power to avoid the violence and arbitrary punishment that are so common at Angola. He constantly worked to better himself while fighting to prove his innocence, he said. Though his life sentence kept him from being able to take most classes offered in the daytime, he took night classes — from risk management, which he later became an instructor for, to mechanics to cooking. When he wasn’t working or in a class, he was in the prison’s hobby shop, where he became a skilled woodworker and learned to make jewelry from a friend.

There, he also met Henry James, another Innocence Project client who, like Malcolm, had been wrongly accused of raping a white woman and sentenced to life in prison without parole. The two shared a passion for woodworking and supported one another through their decades-long fight for freedom.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.