- “Maybe not physically,

- but mentally,

- I’m still in that same situation...”

How a Wrongly Incarcerated Person Became the ‘Most Brilliant Legal Mind’ in ‘America’s Bloodiest Prison’

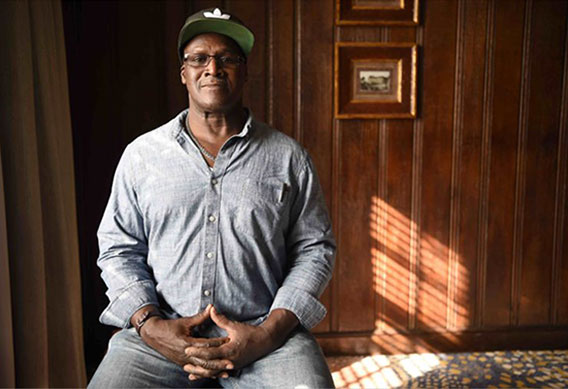

Calvin Duncan spent 28.5 years at Angola, a slave-plantation-turned-prison, for a crime he didn't commit. Now, he's becoming a lawyer.

Special Feature 09.17.21 By Daniele Selby

Updated on Feb. 6, 2022: Calvin Duncan was finally exonerated on Aug. 3, 2021.

“We grew up singing this song — it was a nursery rhyme and each verse was about the crime that we was going to commit that would send us to Angola. And the crime had to rhyme with your age,” Calvin Duncan recalled.

“It went like this: ‘Angola, when I was 1, 1, 1, 1, they booked me for shooting that gun, gun, gun, gun, way down yonder on that farm picking that cotton all day long,’” he sang. “And then someone else would go: ‘Angola, when I was 2, 2, 2, 2, they booked me for sniffing that glue, glue, glue, glue … when I was 3, they booked me for shooting that tree …’ and we would sing these nursery rhymes not having a clue that there was a system that was going to make the song a reality.”

But the crime that ultimately sent Calvin to Angola prison (officially known as the Louisiana State Penitentiary) was one he could never have imagined as a child singing that haunted nursery rhyme — a murder he did not commit.

When Calvin got to Angola, he was sent “way down yonder” to clear the bare cotton stalks left behind after the harvest, for which he was paid just a few cents an hour.

Working the farm at Angola is the first job all men arriving at the prison are given. The prison complex occupies 18,000 acres of farmland, dotted with facilities that house some prison staff and their families and “camps” where those incarcerated live.

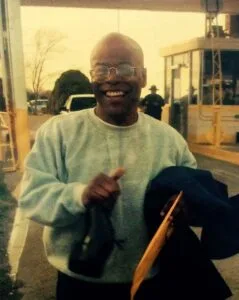

Calvin Duncan the day he was freed. (Image: Courtesy of Calvin Duncan)

From “hell” to “America’s bloodiest prison”

At age 20, Calvin was wrongly arrested for a 1981 murder based on a mistaken cross-racial eyewitness identification and sent to the Orleans Parish Jail. For 4.5 years, he studied the law and fought to prove his innocence from jail, but, in 1985, he was wrongly convicted.

The jail, considered one of the country’s most dangerous, was “hell,” Calvin said. So, by contrast, Angola almost seemed like a “paradise” when he was transferred there after being convicted, despite its reputation as “America’s bloodiest prison,” he said.

Yet, when Calvin first arrived, he was taken aback by the sight around him in the field — endless prisoners, mostly Black men, forced to work the same land slaves had worked 120 years before, while white men with guns looked on from atop horses.

“Doesn’t that sound like slavery to you?” he asked. “When people say this is modern day slavery — this ain’t no modern day slavery. This shit is slavery. It’s no different. It’s identical.”

Prisoners picking cotton at Angola farm under the “convict leasing” system, c. 1901. (Image: Louisiana State University Libraries Special Collection/Andrew D. Lytle’s Baton Rouge Photograph Collection)

To Calvin, the parallels between being processed through the criminal legal systems and being sold into slavery could not be clearer.

“They take us from our land, our country, which, in this case, is New Orleans, and they put us on a boat — only now, that boat is a bus, and they ship us to jail, until we go to the auction block,” he described. The “auction block,” as he sees it, is the criminal district court, where he was sentenced to life in prison for the murder he didn’t commit, sealing his fate at the former slave plantation upon which Angola prison sits.

“Doesn’t that sound like slavery to you?” Instead of being sent to the master of a plantation, people sentenced to 20 years or less are sent to the “master” at Dixon Correctional Institute, Calvin said. And those sentenced to life, like himself, are sent to the “master” at Angola, where the average sentence served is 90 years.

The morning after his arrival at Angola, Calvin was sent for a medical evaluation.

“Just like if you’d come from a slave auction, they bring you to the doctor so the doctor can examine you to determine if you fit to go work in the fields.”

“When people say this is modern day slavery — this ain’t no modern day slavery. This shit is slavery. It’s no different. It’s identical.”

“When people say this is modern day slavery — this ain’t no modern day slavery. This shit is slavery. It’s no different. It’s identical.”

Calvin Duncan

A work crew of prisoners head to the fields at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, La., on Sept. 6, 2001. (Image: AP Photo/Bill Haber)

“The most brilliant legal mind in Angola”

Calvin considers himself lucky in many ways, despite the misfortune and injustice of his wrongful conviction. He never personally experienced much violence, although it was all around him, and, after just one year working in the fields, he earned his GED. His degree and the time he spent studying the law to further his own case enabled him to get “one of the good jobs,” working as “inmate counsel” at the prison — often called a jailhouse lawyer.

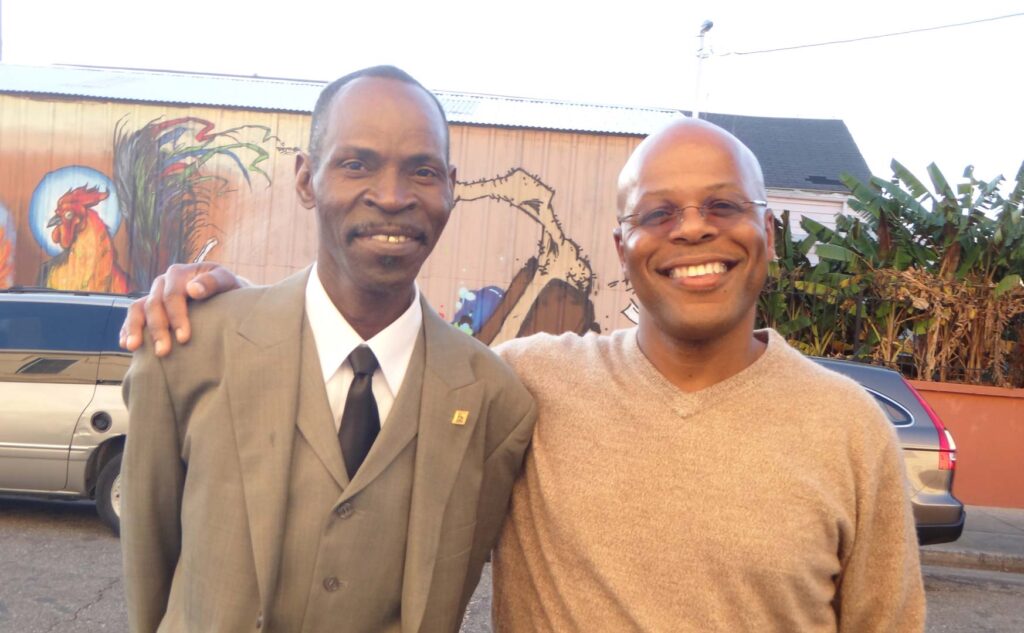

Calvin provided legal advice and acted as counsel to others incarcerated alongside him — all for just 20 cents an hour. For 23 years, he helped people with their appeals and represented people who were mistreated by guards (many of whom lived with mental illnesses or intellectual disabilities). And, in the process, he met countless others who, like himself, should not have been there in the first place, including Innocence Project clients Malcolm Alexander and Henry James.

Calvin Duncan (right) with Innocence Project client Henry James (left) after Mr. James’ exoneration. (Image: Innocence Project)

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.