Why Martin Luther King, Jr. Wouldn’t Be Satisfied With Today’s Lack of Police Accountability

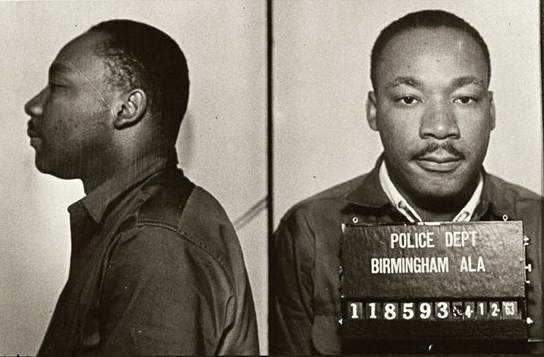

When Martin Luther King, Jr. called for equality and voting rights he also called for an end to police brutality.

01.15.21 By Daniele Selby

In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his historic “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and his words have since been celebrated and taught in classrooms around the world.

The sentence “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” is among the most widely shared from Dr. King’s speech. And while it captures the heart of what Dr. King and the roughly 250,000 people at the march called for — equality — it doesn’t reflect the specific changes for which he advocated: legislation ensuring equal treatment, voting rights, and an end to police brutality.

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality,” he said in that same speech. Today, he would likely be unsatisfied.

In the nearly six decades since Dr. King gave this speech, there has been great progress in advancing equal rights, like the passing of the Voting Rights Act, yet there remains much work to be done to end police brutality and dismantle racism.

Today, Black people who are unarmed or pose a minimal threat to law enforcement are still three times as likely as white people to be shot and killed by the police. And in the past five years alone, there have been 1,254 documented cases in which police officers shot and killed a Black person, many of whom were unarmed.

Racial bias — whether implicit or explicit — plagues the system. And it is seen not only in these fatal shootings, but in the over-policing of communities of color and in violent street encounters with law enforcement. Such biases not only endanger lives but also can contribute to wrongful convictions.

Exoneree Kennedy Brewer visits the Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington, D.C. (Image: Courtesy of Kennedy Brewer)

Implicit bias can taint crime investigations, leading law enforcement to narrowly pursue a suspect who may fit their perception of a “criminal,” rather than thoroughly investigating all potential leads. This was the case for our recently exonerated client Jaythan Kendrick, who detectives doggedly pursued because he was Black and vaguely matched a child’s description of the attacker as seen from a great distance.

Additionally, studies show that Black and brown people are more likely to be stopped, searched, and suspected of a crime — even when no crime has occured — and they’re more likely to be handled with undue force or met with violence in these encounters.

In 2001, Termaine Hicks was on his way home in Philadelphia when he stopped to help a woman in distress. The woman had been viciously attacked, and while Mr. Hicks attempted to help her, police assumed he was the attacker and shot him three times in the back.

Mr. Hicks survived the shooting, but was ultimately wrongly convicted in an effort to cover up the officers’ mistake. He spent 19 years in prison before the Innocence Project was able to secure his release and exoneration last month. Police misconduct, like that in Mr. Hicks’ case, played a role in 35% percent of wrongful convictions resulting in an exoneration, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

“My thoughts and prayers are with the countless others who are not coming home today — or ever because of an impulsive, ill-prepared, and apprehensive cop,” Mr. Hicks said after his exoneration.

“The way that cops approach Black and brown men and women … stems from years of systemic racism. We need a whole new system,” he added.

Termaine Hicks was released from SCI Phoenix Prison on Dec. 16, 2020, in Collegeville, Penn. His brother Tone Hicks and friend Tyron McClendon greeted him upon release. (Image: Jason E. Miczek/AP Images for the Innocence Project)

In order to build that system, prevent wrongful convictions, and end police brutality — as Dr. King called for nearly six decades ago — we must increase police accountability.

“The officers involved in [Mr. Hicks’] had extensive internal affairs files with numerous allegations of lying, planting evidence, excessive force, and substantiated complaints filed by civilians. Had these records been publicly available, Mr. Hicks may not have had to endure so many years of injustice or been wrongly convicted at all,” said Vanessa Potkin, director of post-conviction litigation at the Innocence Project, who represented Mr. Hicks.

Measures to increase police transparency, like the repeal of New York’s 50-A last year, which made police misconduct records public, are a key part of holding police accountable. Several officers involved in recent, well publicized cases of police brutality — like the killing of George Floyd — had prior complaints of abuse or racial bias. And when police misconduct is discovered in a wrongful conviction case, it’s not uncommon to find a history of complaints related to street encounters, and even other wrongful conviction cases, in the records of the officers involved.

Making these records public not only helps to hold law enforcement accountable but allows lawyers to better defend innocent clients. But, police disciplinary records are currently confidential in about half of U.S. states. This means that if and when these histories of misconduct have been uncovered the damage may already have been done with many people having suffered preventable violence or abuse or been wrongfully incarcerated.

“I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells,” Dr. King told the crowd at the March on Washington. “Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.”

Unfortunately, if he were to address a similar crowd today, much of this would hold true.

Dr. King would have turned 92 this year. As we reflect on his legacy this Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and the fight for equality that continued after his assassination, and continues today, the Innocence Project remains committed to fighting for a more just and equal system for all.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

January 18, 2021 at 5:02 pm

An injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. MLK