What You Need to Know About Qualified Immunity and How It Shields Those Responsible for Wrongful Convictions

The Innocence Project and partners push to end a law shielding government misconduct in New York.

Action 04.22.24 By Alicia Maule, Keli Young

The high-profile police-involved deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020 brought the legal doctrine of “qualified immunity” into mainstream conversations, sparking widespread protests and a surge in public interest. Qualified immunity is a judicial doctrine developed by the Supreme Court that shields public officials from liability for misconduct, even when they have broken the law.

In 2020 alone, police in the United States were responsible for over 1,000 fatalities, with Black individuals — like Mr. Floyd and Ms. Taylor — constituting 24% of those deaths. These tragic events spurred significant legislative changes: for instance, Colorado became the first state to abolish qualified immunity, and New York repealed Section 50A, which had previously protected police misconduct records from public scrutiny.

At the Innocence Project, ensuring police accountability is fundamental to preventing wrongful convictions and creating equitable systems of justice for everyone. Together with a bipartisan coalition of organizations including the Americans for Prosperity, American Civil Liberties Union, Institute for Justice, National Police Accountability Project, and Ben & Jerry’s founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, we championed the repeal of qualified immunity in New Mexico in 2021.

To date, police misconduct has played a role in 43% of the 3,497 national exonerations. As a result, we are now actively supporting a campaign in New York (bill S182/A710) to end qualified immunity and hold police and government officials accountable for their actions.

“Police misconduct has contributed to far too many wrongful convictions, and a disproportionate number involving people of color. And too many people have been unable to hold police accountable for violating their constitutional rights because of the doctrine of qualified immunity,” said Keli Young, a state policy advocate at the Innocence Project.

“Ending qualified immunity is a critical step toward creating a more just system and providing exonerees with the financial justice they deserve after government officials violated their rights and unjustly took their freedom. As the vast majority of criminal prosecutions take place at the state and local level, the burden of protecting people’s constitutional rights in New York, falls with the New York State legislature and we are calling on them to pass the Bill to End Qualified Immunity (S182/A710).”

“Ending qualified immunity is a critical step toward providing exonerees with the financial justice they deserve after government officials violated their rights and unjustly took their freedom.”

“Ending qualified immunity is a critical step toward providing exonerees with the financial justice they deserve after government officials violated their rights and unjustly took their freedom.”

Keli Young

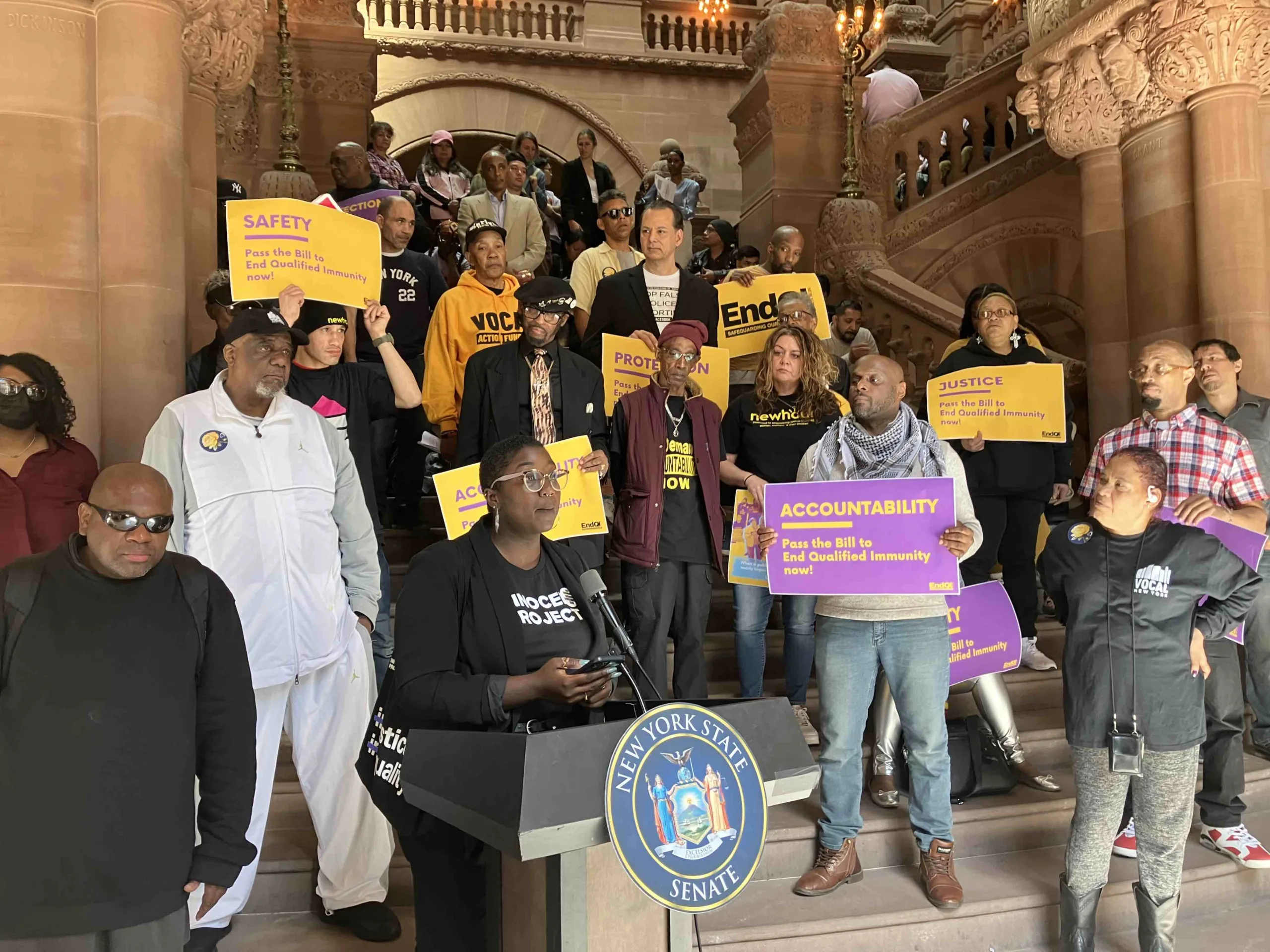

Keli Young speaking at the April 2024 End Qualified Immunity rally in Albany, New York. (Image: Courtesy of the Keli Young)

Here’s what you need to know about qualified immunity:

1. What is qualified immunity?

Qualified immunity is a legal doctrine established by the Supreme Court that protects government officials, including police, from personal liability for constitutional violations unless the right infringed was “clearly established” at the time. “Clearly established” law as stated in the 2018 Supreme Court decision District of Columbia v. Wesby, means that at the time of the officer’s actions, the legal standards were clear enough that any reasonable official would know that what they were doing was unlawful. Therefore, in order for a victim of misconduct to have success suing a government official, they must prove the following:

- The evidence indicates that the conduct was unlawful.

- The officers or government officials were aware or should have been aware that their actions violated a “clearly established” law, as determined by a prior court case that deemed similar police actions illegal.

As a result, courts may recognize rights violations but still deny victims legal recourse, leaving many who were wrongfully incarcerated without justice.

2. When did qualified immunity become an instrument for protecting public officials from accountability?

Originating in 1967 at the end of the Civil Rights Movement as part of federal civil rights law (Section 1983), qualified immunity was meant to balance holding officials accountable and protecting them from frivolous lawsuits while performing their duties. However, many argue that the doctrine signaled a retreat from the protections afforded to Black victims of racial terror by the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act). The 1982 Supreme Court decision in Harlow vs. Fitzgerald further shielded public officials from accountability by stating that officials are immune from prosecution unless they violate “clearly established” rights known to any reasonable person, raising the bar for plaintiffs to challenge abuses.

3. Why is qualified immunity a problem?

Qualified immunity erodes justice for everyone in the following ways:

- Blocks accountability: It makes it nearly impossible to hold officials, particularly in law enforcement, accountable for rights violations unless there is a direct precedent. A direct precedent refers to a previously decided legal case that addresses the same specific issues and circumstances as a current case, and therefore guides the court’s decision.

- Sets an unreasonably high legal barrier: Victims must identify a near-identical precedent, meaning they have to cite a similar case that a prior victim experienced, to challenge misconduct, an often insurmountable legal hurdle. For instance, in 2008, Zackary Stewart, 18, was wrongfully convicted of murder following a false confession coerced by “jailhouse snitches.” Mr. Stewart sued the officers in his case, alleging that his 6th and 14th Amendment rights to counsel were violated when police deliberately placed two incarcerated people in his cell with instructions to gather any information possible related to the charges against him. As a result of qualified immunity, the 8th Circuit Court ruled that there was no clear prior case law that would have clearly warned the police officers in question that their actions were unconstitutional.

- Erodes public trust: The doctrine fosters a view of government officials as above the law, particularly in communities of color disproportionately impacted by police misconduct. The University of Illinois found that of the 50,000,000 interactions people have with police each year, 15% experienced a threat or use of force. Black men represent over 24% of people killed by police, while only comprising 6% of the U.S. population.

- Incurs hefty costs: Victims face both the financial and emotional toll of lengthy legal battles, which often end without resolution because qualified immunity protects government officials responsible for misconduct from accountability.

4. How has qualified immunity prevented exonerees who were victims of government misconduct from seeking justice?

The wrongful convictions of Levon Brooks, Kennedy Brewer, Armand Villasana, Abby Tiscareno, Alan Beaman, and Lana Canen, serve as compelling examples of how qualified immunity makes it virtually impossible for victims of government misconduct to have a pathway to justice:

- Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer were wrongfully convicted — and for Mr. Brewer sentenced to death — in Mississippi of separate murders in 1992 and 1995 and served years in prison. After being exonerated by DNA, which also identified the actual perpetrator of both murders, they sued forensic pathologist Dr. Steven Hayne and forensic dentist, Dr. Michael West, who provided the most important evidence for the prosecution. Dr. Hayne and Dr. West were retained by the State and testified at each trial. The lawsuit alleged that both doctors either intentionally or recklessly falsified their claims that human bite marks were present on the victims’ bodies when, in fact, the marks were the result of normal postmortem decomposition. The 5th Circuit found that because the doctor/defendants were entitled to the defense of qualified immunity, neither Mr. Brewer nor Mr. Brooks would be permitted to engage in the usual comprehensive federal discovery to prove their claims. Instead, the 5th Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgment and dismissed the civil rights lawsuit. At least 31 other people have been cleared having first been wrongfully convicted, arrested, or charged based on the use of bite mark evidence, a now widely discredited science.

You can learn more about Mr. Brooks and Mr. Brewers’ wrongful conviction case by watching The Innocence Files on Netflix. - Armand Villasana was wrongfully convicted in Missouri for kidnapping, rape, and sodomy. Mr Villasana was exonerated by DNA and crime lab notes not disclosed prior to his trial. Mr. Villasana sued the crime lab over constitutional violations under Brady for not disclosing exculpatory documents that could have proved his innocence. However, the 8th Circuit ruled that the laboratory serologist involved was entitled to qualified immunity. The court justified its decision by stating that the Supreme Court had not mandated that law enforcement officials, aside from prosecutors, have a duty to disclose such information.

- Abby Tiscareno, a licensed daycare provider in Utah, was wrongfully convicted of felony child abuse when a child under her care suffered brain hemorrhaging. After calling emergency services, subsequent medical tests supported these findings. However, during her trial, requested medical records from the Utah Division of Child and Family Services (DCFS) were not provided. It wasn’t until a civil suit that Ms. Tiscareno saw pathology reports suggesting the injury could have occurred outside of her care. She was granted a new trial and acquitted. Her subsequent lawsuit for due process violations, alleging that DCFS failed to provide exculpatory evidence, was dismissed due to lack of precedent indicating DCFS’s obligation to produce such evidence.

- Alan Beaman was wrongly convicted in Illinois for 13 years for the murder of his ex-girlfriend. Following his exoneration, Mr. Beaman sued the police officers and prosecutors investigating his case for failing to produce exculpatory evidence, which pointed to two other likely suspects. The 7th Circuit did find that Mr. Beaman’s constitutional rights were violated but could not find precedent to hold that this constitutional violation was clearly established to put the police and prosecutors on notice. As a result, Mr. Beaman’s lawsuit against the investigators in his case was dismissed.

- Lana Canen was exonerated in Indiana after seven years of wrongful incarceration. Her conviction was vacated primarily due to a fingerprint misidentification by an unqualified technician and the state’s lead fingerprint expert, Detective Dennis Chapman. After her conviction, Mr. Chapman recanted his trial testimony and admitted that he lacked the proper training and should not have made the fingerprint comparison in Ms. Canen’s murder case. Ms. Canen sued Mr. Chapman for failing to admit his lack of qualifications as a Brady violation, but the 7th Circuit dismissed the case under qualified immunity.

5. How can you help ban qualified immunity?

The Campaign to End Qualified Immunity in New York seeks to make New York the third state, after Colorado and New Mexico, to hold government officials accountable for violating people’s civil rights. Prompted in part by the police killing of Daniel Prude who was experiencing a mental health emergency, the campaign has intensified calls for legal and systemic reforms around police accountability and the treatment of individuals like Mr. Prude with mental health issues in the state of New York. Mr. Prude, whose family called police for help as he was experiencing a mental health crisis, died after officers put a hood over his head and pressed his face into the pavement. Medical examiners ruled his death a homicide caused by “complications of asphyxia in the setting of physical restraint.” Police involved in Mr. Prude’s case were suspended with pay and never faced charges. Unless qualified immunity is repealed, holding government officials accountable, like those in Mr. Prude’s case, is nearly impossible.

The bill S176/A1402, would repeal qualified immunity in New York with the following benefits:

- Removing the barrier that allows public officials in power to avoid accountability.

- Creating a pathway to justice, allowing people, including those wrongfully convicted, to successfully sue for violations of their constitutional rights.

- Guaranteeing system-wide accountability by allowing government officials to be held liable for civil rights violations and holding the governing agency that employs them financially responsible.

- Supporting systemic change by including a provision in the bill that would help cover legal fees for New Yorkers if the presiding judge on the lawsuit agrees that the case could lead to policy changes, enabling attorneys to take on larger, more complex cases.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

May 6, 2025 at 11:10 pm

December 2, 2024 at 1:29 pm

How can we initiate this nation wide?

I believe that this should be overturned everywhere. No one should be allowed to do to others what they would not do to themselves. It’s we the people not I the people! If you make a mistake and rush to judgment you should be responsible financially and personally remanded. We all make mistakes but if there is knowingly abuse of power then they should be held responsible.