How Racial Bias Contributes to Wrongful Conviction

From police algorithms to the death penalty, the Innocence Project works to tackle the racial injustice ingrained in the criminal legal system and the modern policing methods that perpetuate the inequity.

Special Feature 07.17.21 By Daniele Selby

When the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were written, they protected only the rights of white men — in particular white men who owned property. These documents, upon which our government and legal system were founded, did not extend equal rights to women or to Black people, most of whom were enslaved. And the driving force for the creation of formalized police forces in the U.S. was the desire to monitor and control the movements and actions of slaves — to catch runaways and quash revolts.

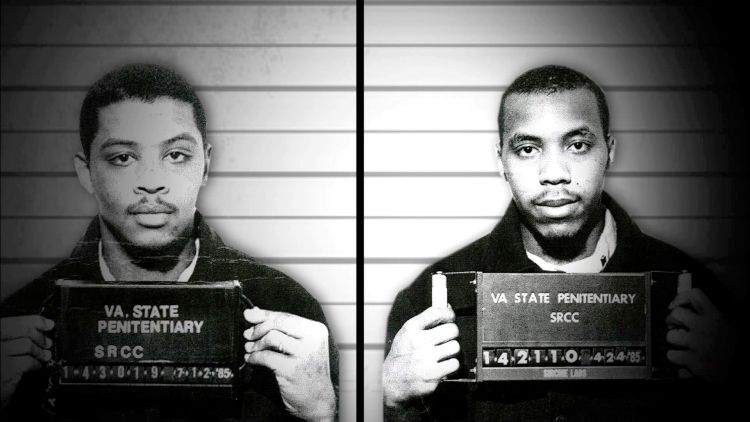

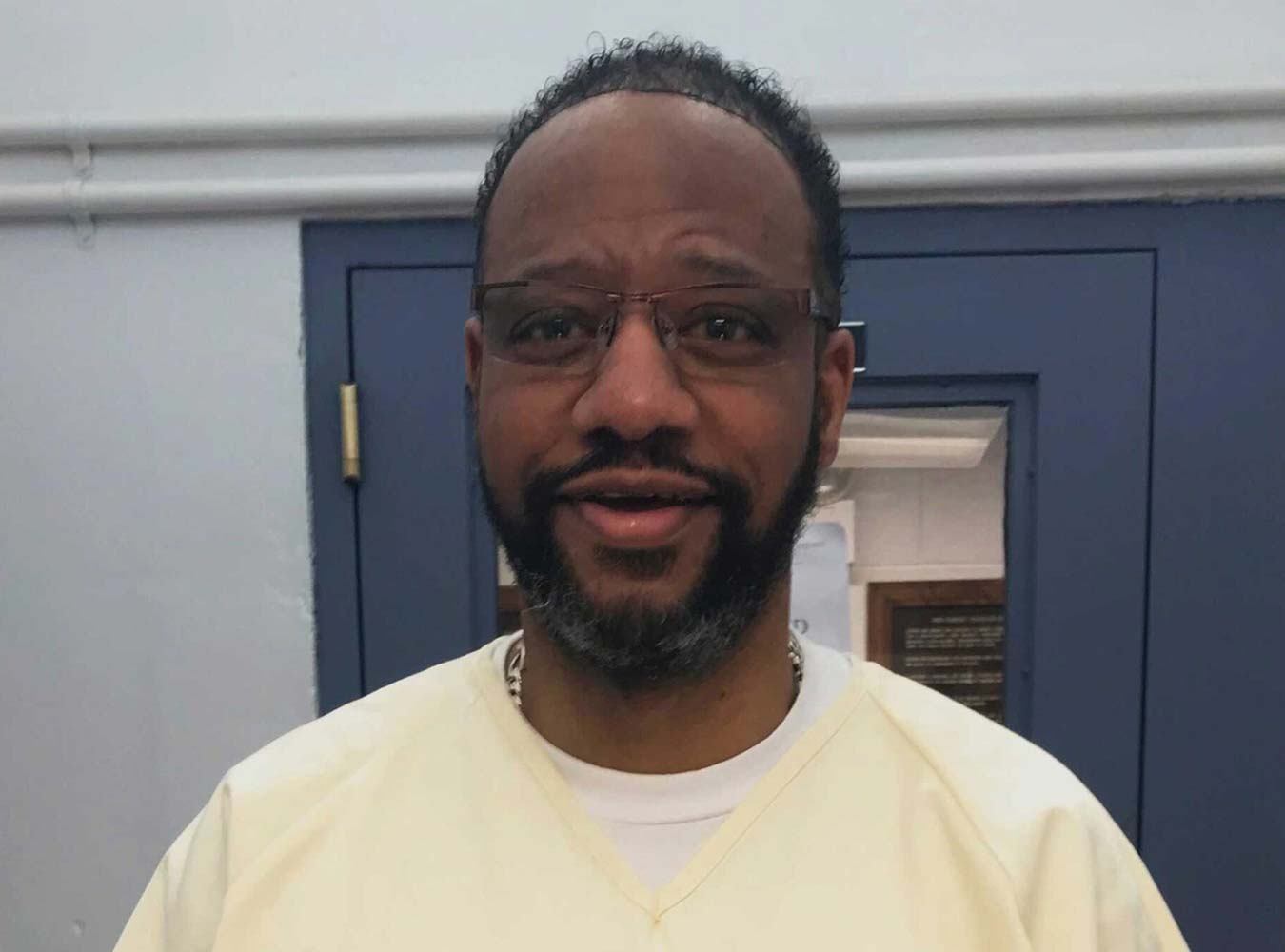

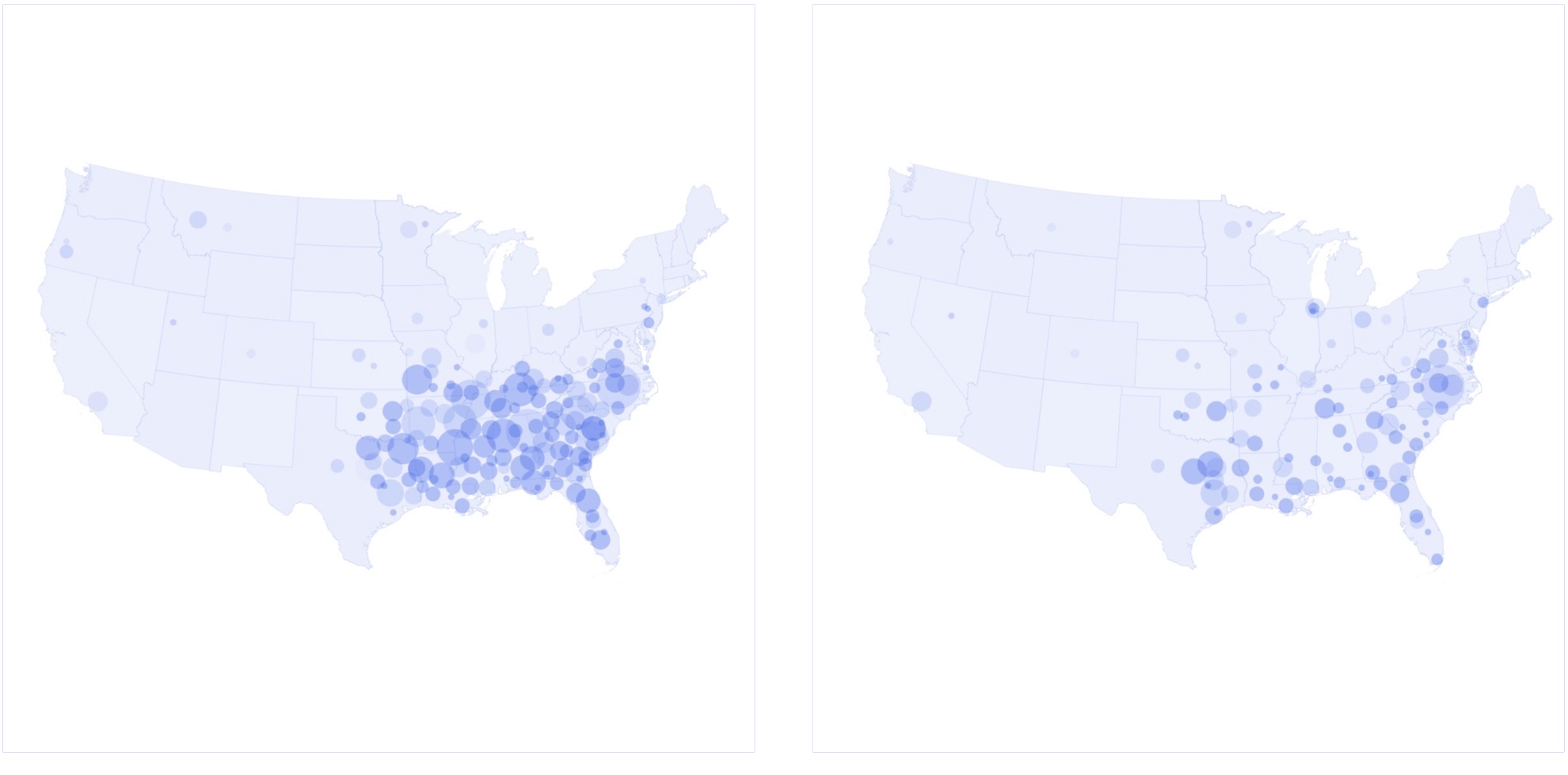

The disproportionate incarceration of Black people today is borne directly out of that dark history and the brutality of the Jim Crow era. Black people account for 40% of the approximately 2.3 million incarcerated people in the U.S. and nearly 50% of all exonerees — despite making up just 13% of the US population. This is, in large part, because they are policed more heavily, often presumed guilty, and frequently denied a fair shot at justice.

At the Innocence Project, we’ve seen that the majority of wrongly convicted people are those who are already among the most vulnerable in our society — people of color and people experiencing poverty. Two-thirds of the 232 people whose release or exoneration we have helped secure to date are people of color, and 58% of them are Black.

That’s why we are working to tackle the racial injustice ingrained in the criminal legal system and the modern policing methods that perpetuate the inequity.

Eigenfaces from AT&T Laboratories Cambridge. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

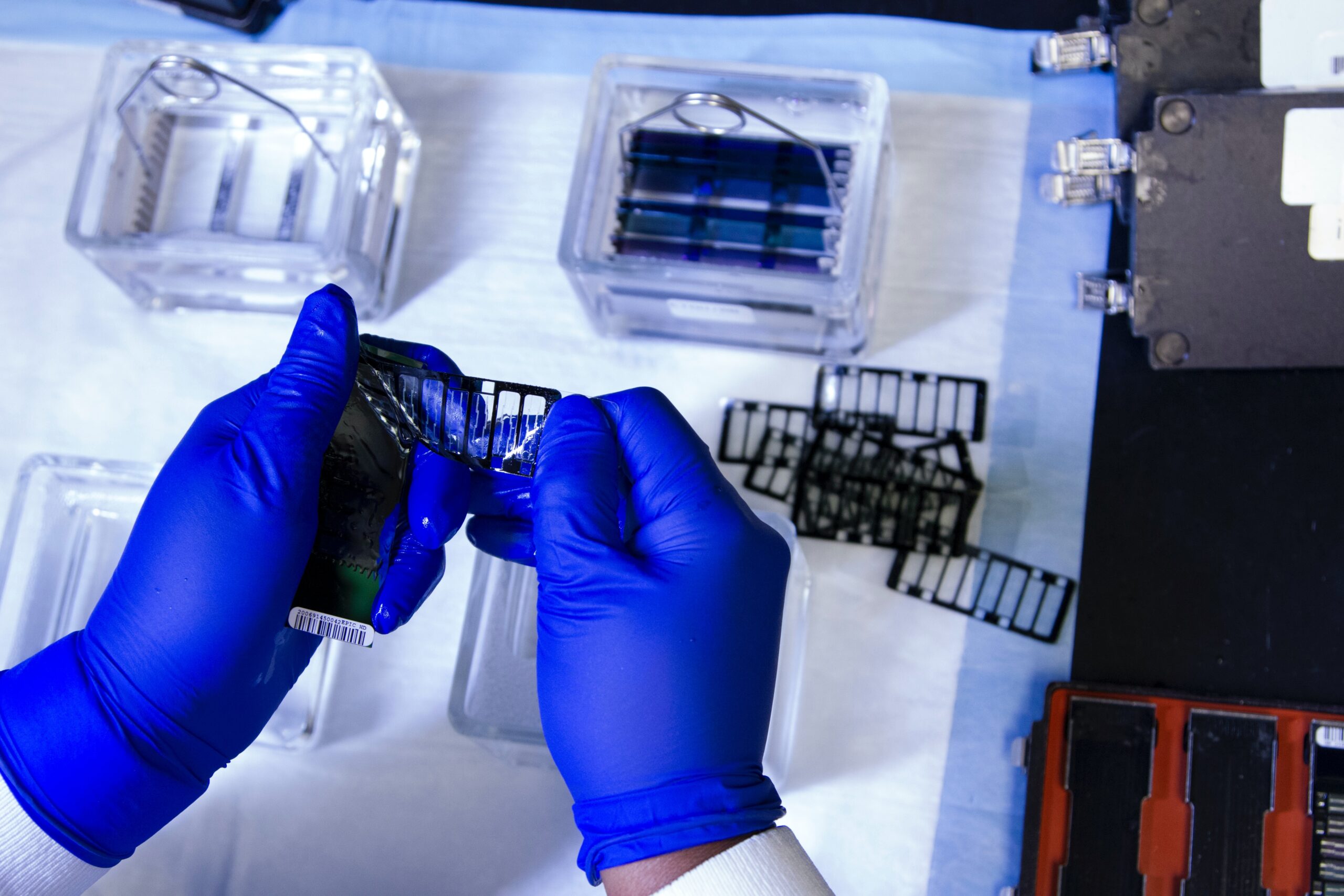

Biased policing tools

As technology has advanced, law enforcement agencies have explored its applications to policing, resulting in the use of algorithms that attempt to predict who might be more likely to commit a crime and facial recognition tools that aim to identify the perpetrator of a crime using image databases. These might sound like tools that could make communities safe, but the reality is that they encroach on citizens’ privacy rights and endanger Black and brown people.

The algorithms used to predict future crimes are based on historical crime data, and research has found that racial bias is ingrained in this data because it reflects police activity and arrests rather than actual crimes committed. And those biases get amplified by these algorithms.

For example, a risk assessment algorithm may rate a person a high risk for committing another crime — likely garnering them a higher bail — because of high arrest rates in their neighborhood. However, the algorithm doesn’t take into consideration that poor communities and communities of color are typically policed more heavily and, as a result, see more arrests. It also does not factor in the “false positives” — cases in which the person was later determined to be innocent — produced by these large numbers of arrests.

A 2016 ProPublica investigation found that the risk assessment algorithm used in Broward County, Florida, for example, incorrectly predicted that Black defendants would commit future crimes at twice the rate as white defendants. The tool also underestimated white defendants’ risk of committing future crimes.

Already, tools like facial recognition software have come under fire for racial bias. Studies have found that facial recognition tools are relatively successful at identifying the faces of white males, but falsely identify Black and Asian faces 10 to 100 times more often than they misidentify white faces. Facial recognition algorithms also struggle to accurately identify women’s faces. Research shows that the software identifies young Black women with the poorest accuracy.

So far, at least three men — each of whom is Black — are known to have been wrongfully arrested based on misidentifications by facial recognition software.

Currently, no framework currently exists to inform the use of these predictive algorithms. In addition to supporting bans or regulations of certain technology used for policing, such as facial recognition software, the Innocence Project supports state-based legislation like New York Senate Bill S79. The bill would halt the use of biometric surveillance technologies until a regulatory task force is set up to approve existing and new biometric surveillance technologies, including predictive policing tools and investigative systems such as gang databases.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.