Facing Execution in One Month, Innocent Mom Melissa Lucio Still Hopes She’ll Be Free One Day

Melissa Lucio has maintained her innocence on death row for 16 years.

Special Feature 03.22.22 By Daniele Selby

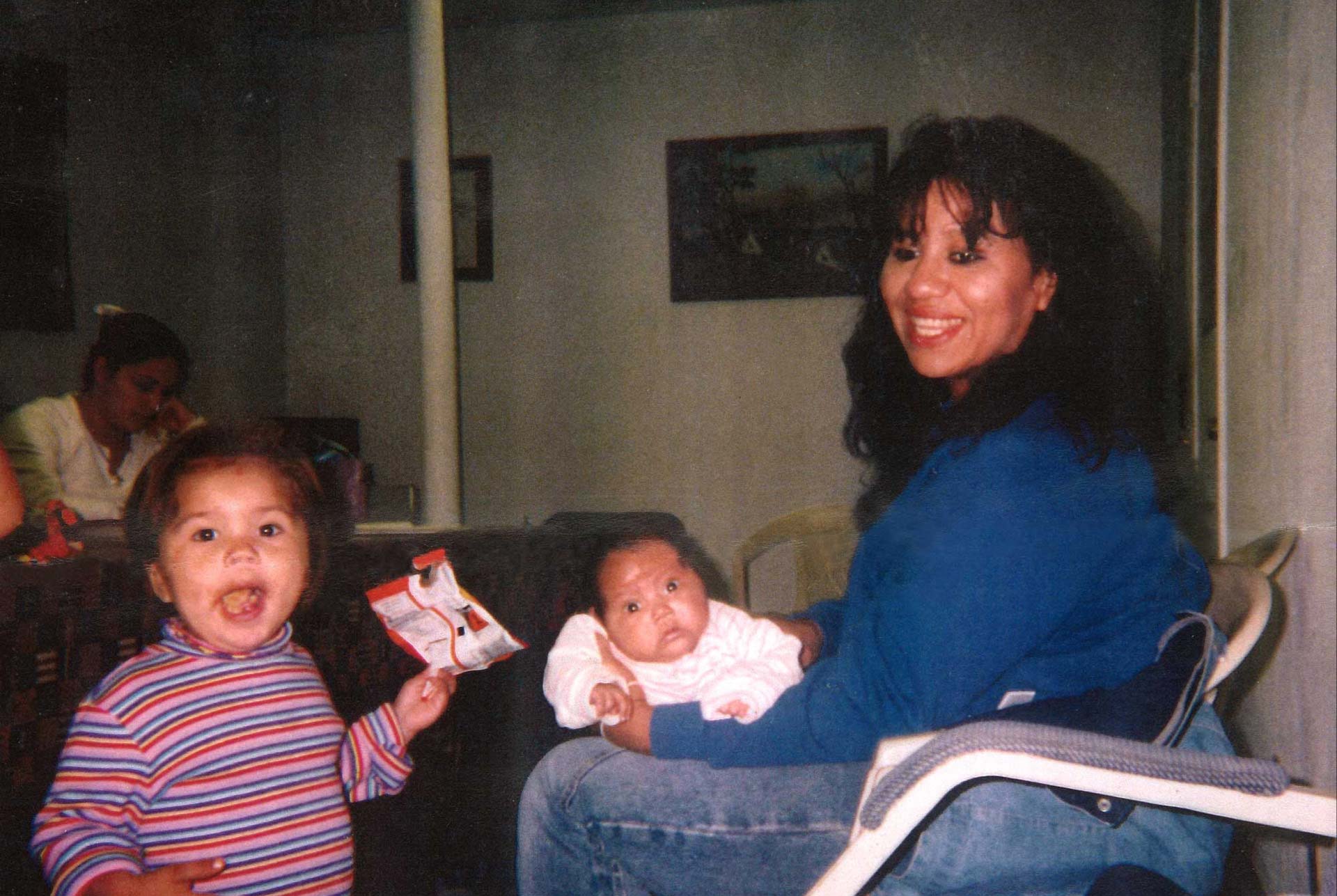

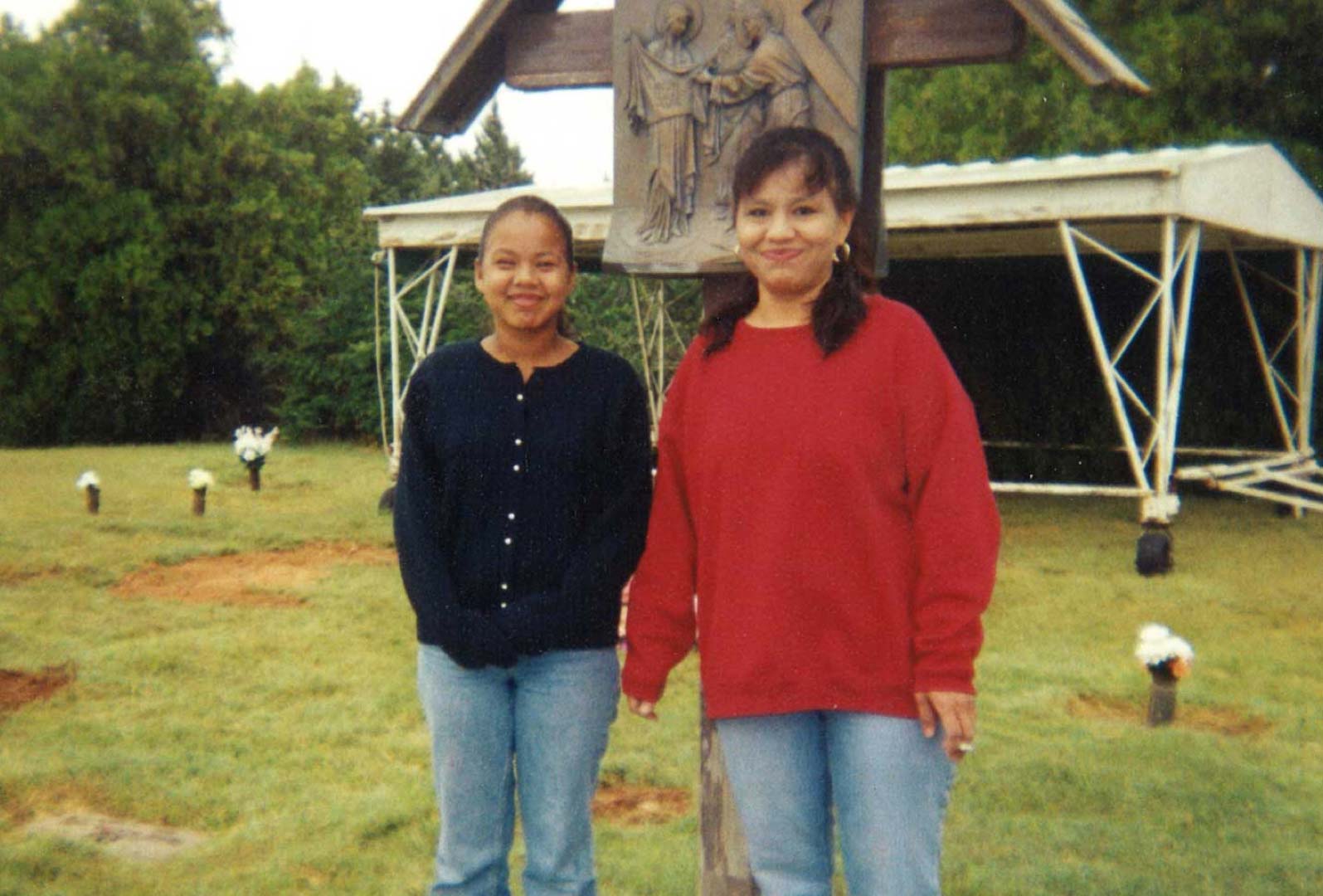

Mariah Alvarez on her birthday. (Image: Courtesy of the Lucio family)

Latest case update from April 12, 2024: The judge who presided over Melissa Lucio’s original trial, Judge Arturo Nelson recommended that that Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturn Ms. Lucio’s conviction and death sentence. That recommendation is now before the Court of Criminal Appeals, which in Texas, is the only court that can overturn a criminal conviction.

The article below was written in 2022:

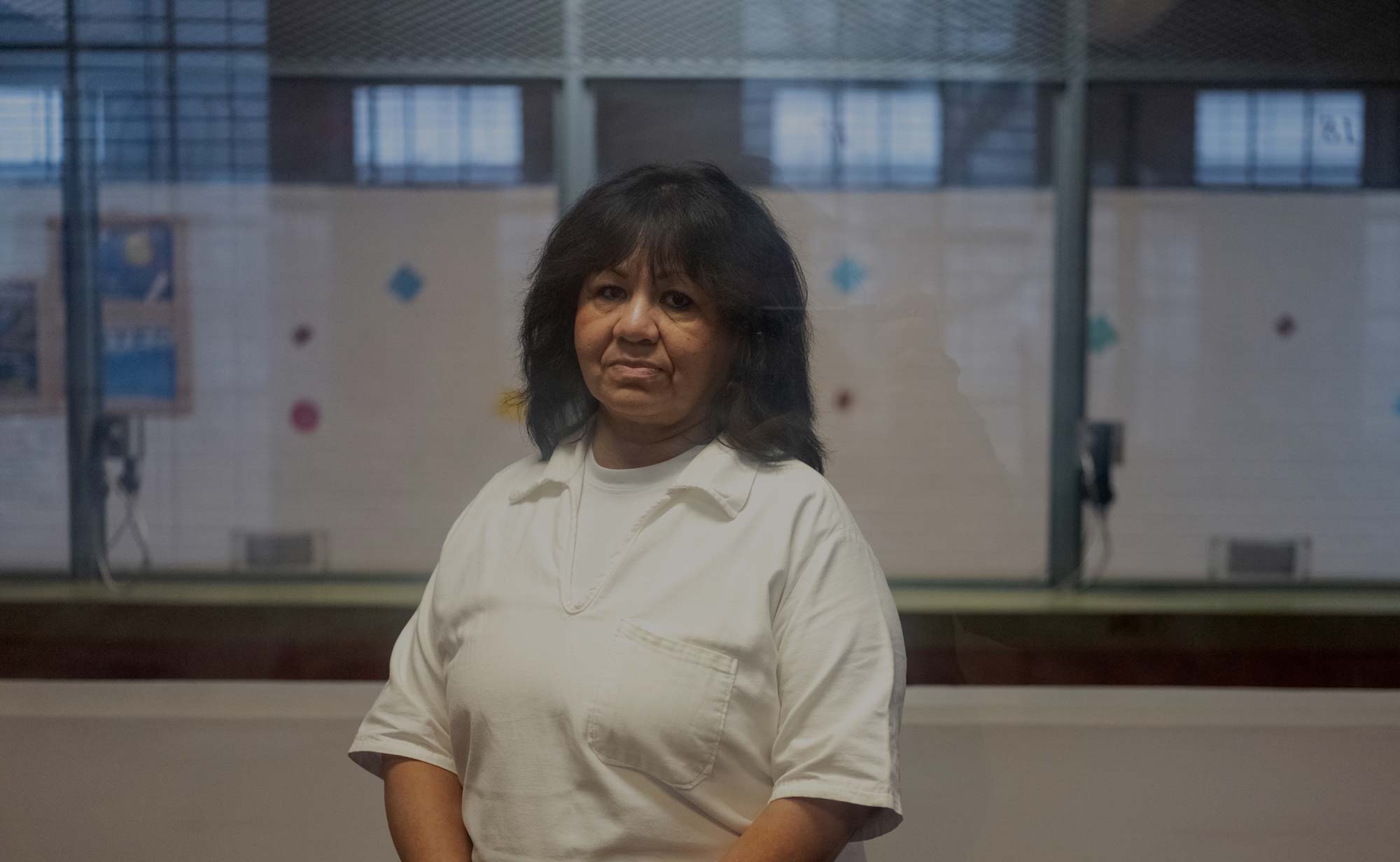

“Mariah was my baby, I loved her,” Melissa Lucio said of her youngest daughter. Through the glass of the visitation room at Mountain View Unit, a Texas women’s prison, her anguish is visible. Ms. Lucio has never had a chance to truly grieve her baby, who died in 2007, because she’s spent the last 15 years incarcerated for a crime that never occurred: Mariah’s murder.

At 53, Ms. Lucio has survived a lifetime of unimaginable tragedies and trauma — the most devastating of all being her 2-year-old daughter’s death after an accidental fall. Yet, in less than 40 days, the State of Texas plans to execute Ms. Lucio, adding another layer of tragedy to what has already been the greatest one of Ms. Lucio’s life.

To date, 185 people have been exonerated from death row. These innocent people came dangerously close to being killed for crimes they did not commit, and Ms. Lucio faces the same fate. The power to stop her execution before it’s too late lies in the hands of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott.

So far, more than 100,000 people have signed a petition supporting Ms. Lucio and calling for her execution to be stopped.

“I want to tell my supporters that I’m very grateful for all the letters they have sent me, their words of encouragement, their support, and their belief in me,” Ms. Lucio said. “I’m just very excited that so many people have signed the petition, so many have believed in me and know that I was wrongfully convicted, I’m hoping that I will be set free from this place.”

Today, Ms. Lucio’s legal team filed a petition to the governor and the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, asking them to grant Ms. Lucio clemency. The petition includes statements from many experts on the coercive tactics used against Ms. Lucio, the misleading evidence presented at her trial, and declarations from five jurors who served at her trial stating they have grave concerns about evidence that was withheld and would support relief in her case.

Editor’s note: The following contains difficult material relating to sexual abuse and domestic violence. If you have experienced sexual abuse and want to speak to someone, call the free and confidential National Sexual Assault hotline (1-800-656-HOPE or 1-800-656-4673). You can also receive help via online.rainn.org, which is available 24/7.

How a tragic accident became a wrongful conviction

Mariah, named after Grammy-winning singer Mariah Carey, was the 12th of Ms. Lucio’s children at the time. And, like the singer, she had a playful personality.

“She was a funny little young toddler,” Ms. Lucio recalled. Mariah loved to play with her brothers, even though they were bigger and older. And she always chose to play with them over her toys, despite having a foot that turned inwards and made her unsteady when walking and prone to tripping. “She would see them playing and throw herself on top of them,” Ms. Lucio said.

Ms. Lucio had once dreamed of working at a school or daycare where she could work with children, but that dream slipped farther and farther away each time she found herself in another abusive relationship with no way to raise herself and her children out of poverty on her own.

Instead, she channeled her dream into her children, who became her solace.

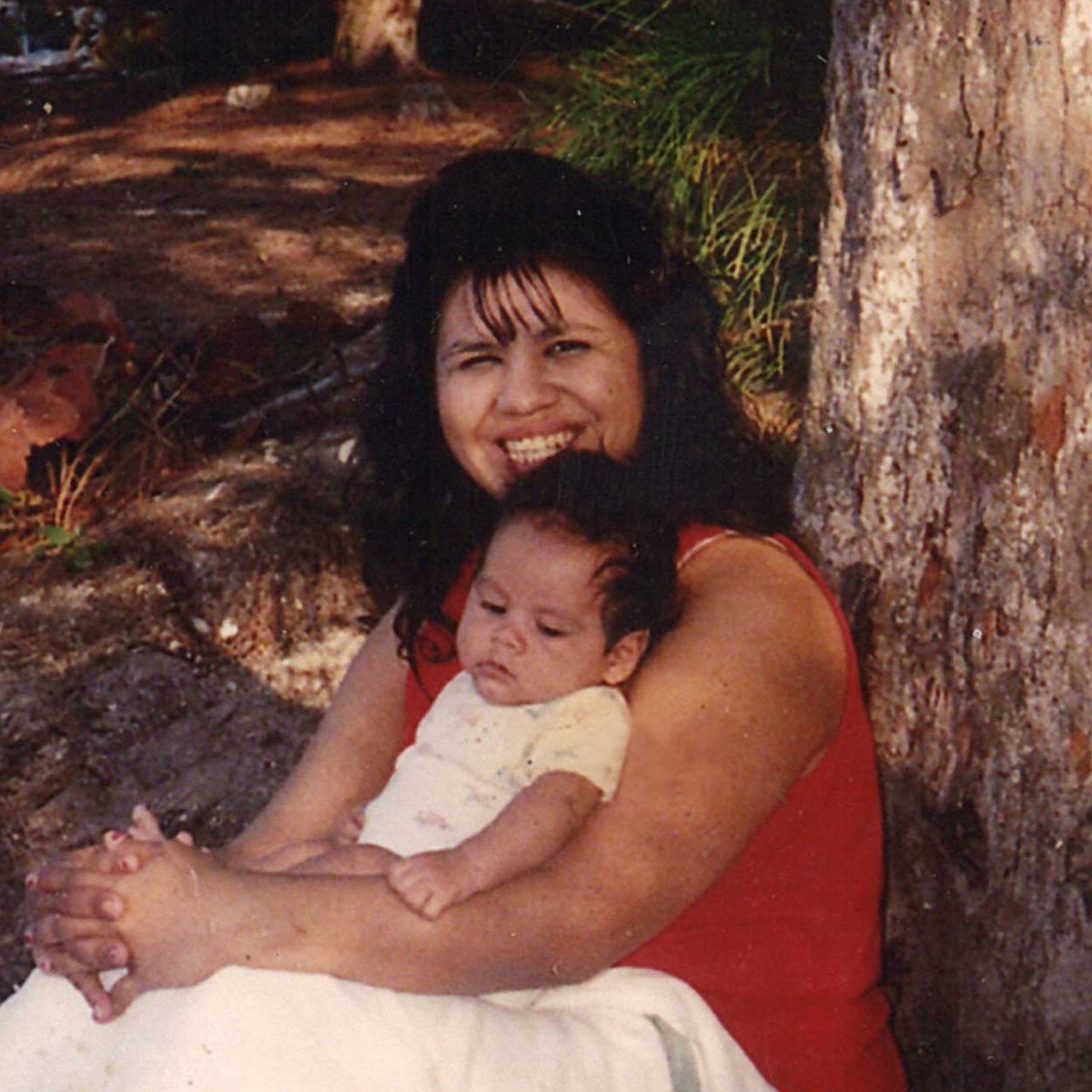

Melissa holds Mariah, while looking on at her daughter Adriana. (Image: Courtesy of the Lucio family)

On Feb. 15, 2007, Mariah fell down a flight of stairs while the family was in the midst of moving homes. The toddler didn’t appear seriously injured, but, two days later, she wouldn’t wake up from a nap. Ms. Lucio immediately called for help, and Mariah was taken to the hospital but could not be resuscitated and died. That same night, Ms. Lucio was taken in for questioning.

In truth, Ms. Lucio’s fate began to take shape the moment emergency responders arrived at her home and made the first of a series of assumptions and misjudgments that turned the loss of her child into an even greater nightmare than anyone could have imagined.

Ms. Lucio told an emergency responder that her daughter had fallen down a flight of stairs days earlier. Not realizing the fall had occurred at the family’s previous home — an apartment only accessible by a 14-step staircase — the EMS worker took note of the handful of steps leading into their new home. He thought it “odd” that the child would have bruises from a tumble down just a few steps. And he felt that Ms. Lucio, who was in complete shock, “didn’t act at all like what [he] would expect of a mother.”

When police arrived, he reported his doubts to them.

The police proceeded to investigate the situation with suspicion. And when Ms. Lucio’s reaction to the unimaginable loss of her baby did not align with their preconceived notion of how a woman should act when she loses a child, they leaned further into those suspicions.

Nearly 30% of exonerated women were wrongly convicted of harming a child.Women — in particular, mothers — accused of harming a child tend to be viewed more critically than men and are often demonized in the media. Nearly 30% of exonerated women were wrongly convicted of harming a child, according to the data from the National Registry of Exonerations, of those women 1 in 5 falsely confessed. About 71% of exonerated women were wrongly convicted in cases where no crime occurred — cases in which the “crime” was later found to be an accident, a death by suicide, or fabricated.

Police were convinced that Mariah had been abused and fixed their attention on Ms. Lucio.

Just two hours after Mariah died, police began interrogating Ms. Lucio, whom they presumed was guilty of having murdered her child.

For five hours, police showed Ms. Lucio photos of her deceased child, berated her and told her she was a bad mother, and intimidated her. Periodically, they suggested that Ms. Lucio might face less severe punishments if she admitted she had abused or killed her child because she had been “just frustrated” or that it had been an “accident.” This coercive interrogation tactic — alternately threatening a person and then suggesting leniency — is known to produce false confessions and pressure innocent people to admit to crimes they did not commit.

Ms. Lucio, who was pregnant with twins at the time of the interrogation, asserted her innocence more than 100 times. Her perseverance through the grueling and traumatic interrogation was particularly noteworthy given the lifetime of violence and abuse she has survived. Experts on false confession have confirmed that Ms. Lucio’s history of trauma and related mental health issues make her uniquely vulnerable to falsely confessing under such coercive conditions.

By 3 a.m., it had become clear to Ms. Lucio that the interrogation would not end until the officers heard what they wanted to hear. So, pregnant, exhausted, grieving, and afraid, she said, “I guess I did it.” A statement she hoped would appease them and end the interrogation, which it did.

Ms. Lucio didn’t know then that her words would be misconstrued in court by the prosecution as a false confession, and that she would never get to go home again.

“I’m hoping that I will be set free from this place.”

“I’m hoping that I will be set free from this place.”

Melissa Lucio

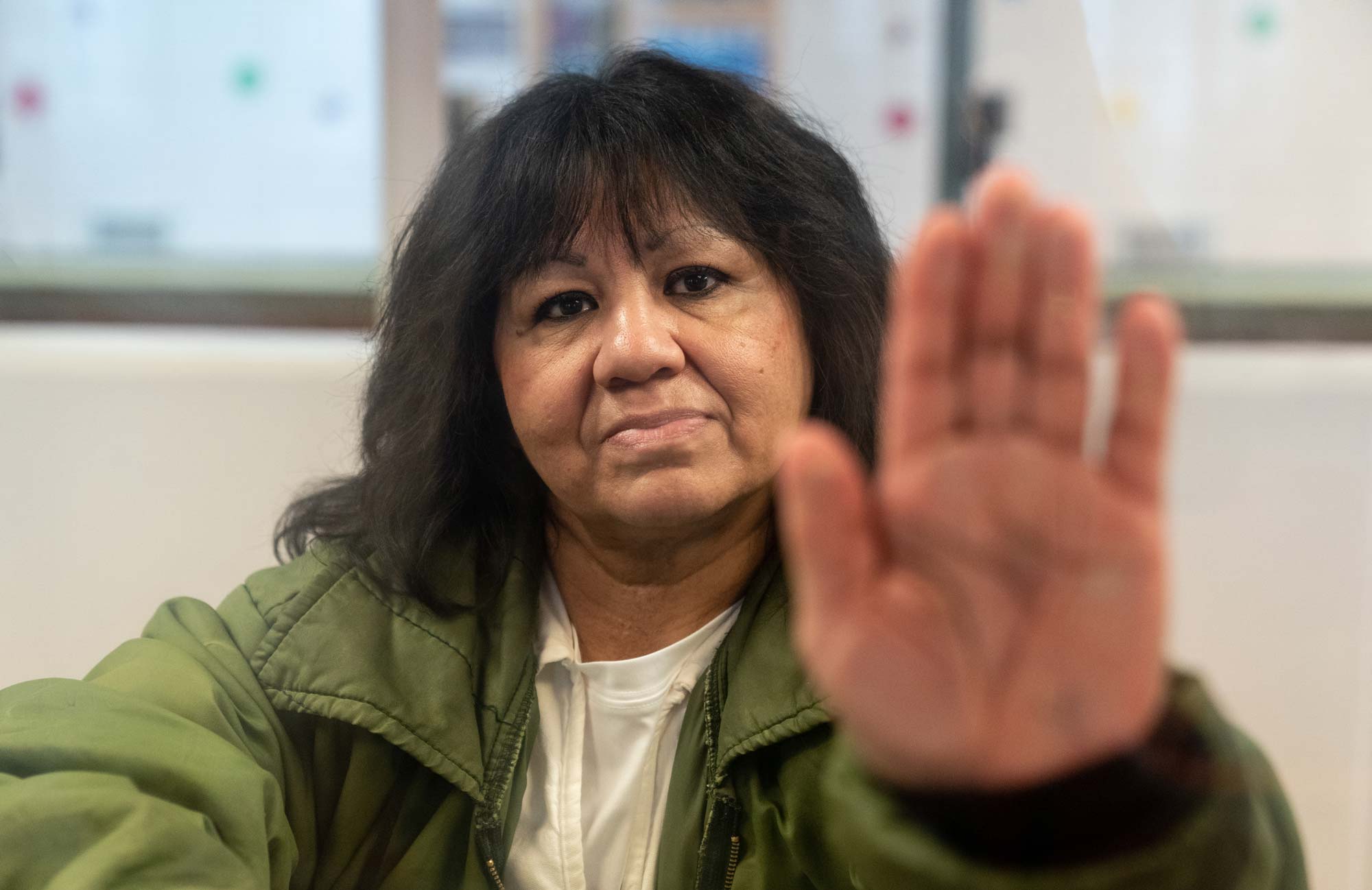

(Image: Ilana Panich-Linsman for the Innocence Project)

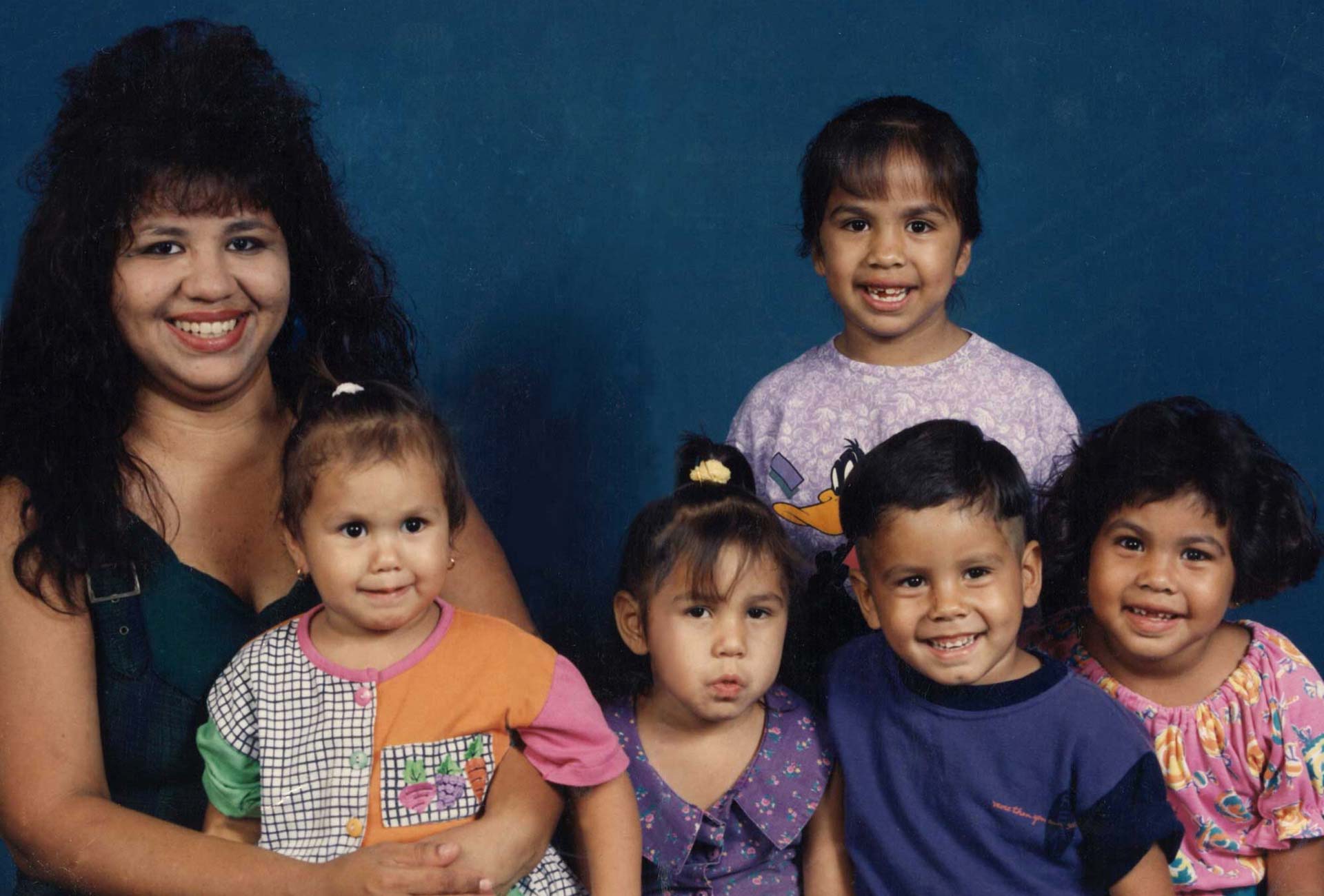

Melissa Lucio (Image: Courtesy of the Lucio family)

‘As normal as we could be’

Life with 12 children was hard, Ms. Lucio, who is Catholic, admitted. The family lived in poverty, and Ms. Lucio, although a loving and patient mother, struggled to provide for them. She did the best she could to care for her children. On each of their birthdays they would throw small parties, making sure they had piñatas to celebrate with their friends and what gifts they could afford. But the family was intermittently homeless and often had to turn to church-run programs to feed themselves.

At home, Ms. Lucio faced constant abuse. Her partner — Mariah’s father — repeatedly raped her, choked her, and threatened to kill her. To keep her isolated and dependent on him, he would lock her at home and take the keys with him, ensuring she could not escape the cycle of abuse she’d experienced her entire life.

At the age of 6, Ms. Lucio was sexually assaulted by close family members, beginning a pattern of physical and sexual abuse that continued into her adulthood. At 16, she married a man she hoped would help her escape her abusive situation, but he, too, was violent toward her. He also misused alcohol and sold drugs.

It was nothing like the escape and stability she had hoped for. And while Ms. Lucio had been able to get married before she reached the legal age of marriage in Texas (18) with her mother’s consent, she was still a minor, meaning she could not legally end the marriage. Trapped, Ms. Lucio began using drugs.

By the age of 23, Ms. Lucio had five children. Then, her husband abandoned her and their young children. She was initially so stunned by the disappearance of her husband, upon whom she and her children depended, that she even reported him missing to the police. After it became clear he wasn’t missing but had chosen to leave, Ms. Lucio began a relationship with the man who would become Mariah’s father.

At one point, Ms. Lucio’s children were taken into foster care, while Ms. Lucio worked to stabilize her life and home. She was allowed to see her children for a few hours each week. Ms. Lucio described that period as one of the hardest in her life.

“When the visit was over, I never wanted to leave,” she said. Each child vied for a turn in their mother’s lap during their weekly visits, and Ms. Lucio would bring the children toys and small gifts. “What we could afford,” she said.

Ms. Lucio made a special effort to spend time with Mariah, then the youngest of her children, during their visits, holding her and speaking to her in “baby talk” to maintain their bond.

“… I never wanted to leave.”

“We took pictures [with the kids] … lots of pictures with them. We told them everything would be okay, and they’d be coming home soon,” Ms. Lucio said.

When Child Protective Services approved the children’s return home, Ms. Lucio said it was a “blessing” just to be a family again. She relished being able to cook for her children and hearing her children yell “Mommy!” when they spotted her car after school.

They were a normal family again, “as normal as we could be,” Ms. Lucio recalled. Those months — when all Ms. Lucio’s children were back home with her — were the last “normal” months she’s had in 15 years.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.