The Fierce Urgency of Now

The current legal landscape requires us to be even more vigilant in advancing criminal and racial justice reform.

09.12.22 By Christina Swarns

I begin my third year as the Executive Director of the Innocence Project with a deep sense of urgency about our mission to free the innocent, prevent wrongful convictions, and create fair, compassionate, and equitable systems of justice for everyone.

I firmly believe that the Innocence Project is the most transformative criminal legal system reform organization in American history. Just take a look at this new digital timeline that captures our milestones over the past 30 years.

I am blindingly proud that, in the last year alone, we helped to free or exonerate 10 wrongfully convicted people, helped prevent the execution of three people — including Melissa Lucio in Texas — and passed pioneering laws in Delaware, Oregon, Utah and Indiana.

And I am nothing short of alarmed by the recent decisions of the United States Supreme Court that will make it harder for the hundreds of thousands of innocent people who are behind prison walls to prove that they were wrongfully convicted and seek redress for law enforcement violations of their rights.

So, notwithstanding our extraordinary successes, I cannot help but be reminded of the profound words of Ella Baker: “We who believe in freedom cannot rest.”

Advocates of Melissa Lucio were seen during the yearly Cesar Chavez march in San Antonio, Texas on March 26, 2022. (Image: Christopher Lee for the Innocence Project)

Why the Sense of Urgency and Alarm?

In May, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Shinn v. Ramirez and Jones, closed the federal courthouse doors to evidence of ineffective assistance of trial counsel — attorney errors that prevented juries from hearing evidence of innocence — that was not first presented to the state courts due to the incompetency of state post-conviction counsel.

This decision leaves countless people without a court to hear their evidence of innocence or evaluate the performance of their trial lawyers. The vast majority of people that go through the state criminal court system — as many as 90% — are represented by public defenders, many of whom are under-resourced and overburdened. That means that, in some cases, critical evidence of innocence is overlooked at trial and claims of error that would correct a wrongful conviction are not raised in post-conviction appeals. Without the federal courts to hear such unpresented evidence of innocence, innocent people will be stuck in prison.

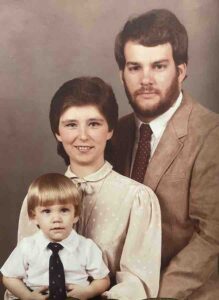

Charles McCrory, wrongly convicted of killing his wife, with his wife Julie Bonds, and their son. (Image: Courtesy of the McCrory family)

How do I know? Because many of our clients are represented by ineffective counsel for which there must be adequate recourse. For example, Charles McCrory, who we represent along with the Southern Center for Human Rights, has spent the last 37 years in prison in Alabama, serving a life sentence that was imposed after he was convicted of a murder he didn’t commit after a trial at which his state-appointed counsel failed to present the ample evidence of his innocence, including an alternative suspect who committed a similar crime. The integrity of the legal system requires accountability for attorney failures like those in Mr. McCrory’s case. For many cases, the Supreme Court’s decision in Shinn prevents it.

In June, the Supreme Court ruled in Vega v. Tekoh that the police cannot be sued in federal court for failure to give Miranda warnings — advising of the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney — to people in custody. The decision eliminates an important deterrent to police violation of rights that are important to preventing false and coerced confessions. Significantly, this decision came at a time when policies taking aim at police misconduct are gaining momentum around the country — indeed, the executive order signed by President Biden in June seeks to improve police accountability and includes measures that would help reduce the risks of wrongful convictions.

These decisions ignore the lessons that our cases, over the last 30 years, have taught the world about the prevalence of wrongful conviction in our country.

Where Do We Go From Here?

At the start of our 30th year, we announced ambitious new initiatives that build on our record of success while also meeting the very real challenges of this moment. They include:

Deepening our commitment to addressing racial bias in the criminal legal system by ensuring that our intake procedures surface cases where racism contributed to the wrongful conviction of an innocent person, our litigation strategies take into account the latest law and science on racial bias and discrimination, our social work policies and practices are informed by the unique challenges posed by discrimination and unconscious bias and our policy and education campaigns — including our commitment to evaluate and challenge emerging technologies such as facial recognition software — contribute to dismantling systemic racism.

This is an institutional imperative because racial bias is a powerful driver of wrongful conviction. Just look at the statistics:

- Two-thirds of the 239 people we have helped to free or exonerate are people of color and 58% are Black.

- Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than white people.

- A Black person convicted of sexual assault is 3.5 times more likely to be innocent than a white person convicted of such a crime.

- And innocent Black people are 12 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of drug possession than innocent white people.

We are widening our intake criteria to include a select number of non-DNA cases because there is no biological evidence in the overwhelming majority of violent felony convictions. The cases of Mr. McCrory and Rosa Jimenez — who was wrongly convicted of murder, based on faulty medical evidence, after a child in her care died from a tragic accident — stand as powerful reminders of the breadth of the problem of wrongful conviction and compel us to do more to meet this urgent need.

Rosa Jimenez in downtown Austin, Texas, on March 4, 2021. (Image: Mary Kang for the Innocence Project)

Our scientific literacy program will educate attorneys and judges on the limitations of forensic evidence. If the attorneys who represented Eddie Lee Howard and the judge who presided at his trial had been better versed in the science underlying the now widely discredited “bite mark” evidence that was used to prosecute and convict him, Mr. Howard might not have lost 26 years of his life to wrongful conviction.

And we will continue to push for greater accountability in policing by working to make police disciplinary records available, banning qualified immunity, and enabling civilian oversight of law enforcement. We will continue to work to ban police deception in the interrogation of children because we know that such a prohibition could have prevented the wrongful conviction of the Exonerated Five who were teenagers at the time of their arrest and interrogation.

What Can You Do?

We cannot do this work without you. We have been humbled, heartened, and inspired by the extraordinary support we have received over the course of our 30-year history and in this last year alone.

Yet, again, “we who believe in freedom cannot rest.”

Given the challenges ahead, there is much more work to do. In addition to providing critical financial support and responding to our urgent calls to action, all of us can use our votes to drive the transformational change necessary to prevent wrongful convictions.

Many of the public officials we elect — from district attorneys to judges to council members to sheriffs — have a huge influence on the operation and administration of our criminal legal systems, including those that prevent and correct wrongful convictions. For example, district attorneys can and should create and support conviction integrity units to review past convictions for errors. Such a unit within the Philadelphia DA’s office worked with the Innocence Project to vacate the conviction of Termaine Hicks, who spent 19 years in prison based on the false testimony of police officers.

Every person who seeks to hold a public office that has influence over the administration of the criminal legal system should be required to set forth a detailed plan for ameliorating arbitrary disparities, holding systems and actors accountable and addressing the problem of wrongful conviction.

This should be a prerequisite for earning any of our votes.

This is the “fierce urgency of now.”

With deep gratitude for your partnership in this hard and important work,

Christina Swarns

Executive Director, Innocence Project

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.