- “The dungeon

- was the last place

- I wanted to go...”

‘The Dungeon Was the Last Place I Wanted to Go’: An Exoneree’s Story of Survival at Angola Prison

Henry James was a young father with two babies when he was wrongly convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Special Feature 09.17.21 By Daniele Selby

As Henry James recalled, there were only three ways to get out of working the field at the Louisiana State Penitentiary — get sick, get hurt, or catch a rabbit.

In his time at Angola, as the Louisiana State Penitentiary is known, Henry caught many rabbits.

“You had to run behind it and catch it with your hands and bring it to the free man. And he would take him home and eat him,” Henry said. “They would give you a half a day off if you could catch one rabbit. For two, you could get a whole day off.”

The “free men” whom Henry referred to were the staff and guards — people who were free to go home at the end of the day, unlike Henry and the other incarcerated people.

Only once, to avoid the brutal heat, did Henry get hurt, cutting his own knee with a razor blade. For the most part, he said, he worked hard in the fields, trying to avoid trouble because he had a bigger goal: “To receive justice for the wrong that was done to me.”

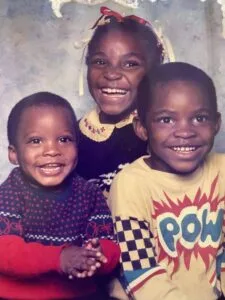

From left to right: Henry’s stepson Tristian, daughter O’Sheena, and son Laurendine. (Image: Courtesy of Henry James)

“They snatched that away”

On a fall afternoon in 1981, police arrested Henry at the welding company where he worked in New Orleans. The 20-year-old father had recently started the job and was excited to be able to support his two young kids — his daughter O’Sheena, who was 1 at the time, and his newborn son Laurendine.

“I was just trying to live a decent life like the next man and I had babies that I was just trying to work and take care of, but they snatched that away from me,” said Henry.

In April 1982, Henry was wrongly convicted of rape and sentenced to life in prison without parole, even though serological testing had excluded him as the attacker — a fact that his lawyer failed to share with the jury.

He was convicted largely based on the erroneous identification of the rape survivor, a white woman who lived next door to Henry in New Orleans’ Jefferson Parish. The day before the attack, Henry had spent most of afternoon helping the woman’s husband repair his car. Henry and the woman had spoken later that night after Henry informed her that he’d been in a car accident with her husband that had resulted in her spouse’s arrest. The following morning, she was raped at knifepoint by someone who entered her home.

The woman did not describe her attacker as someone she knew, nor did she tell police that he was the same person who had spent the previous day with her husband. Yet, after reviewing dozens of photos of Black men in a book, she identified Henry as her attacker.

Mistaken eyewitness identifications are a leading cause of wrongful conviction and have contributed to approximately 28% of wrongful convictions resulting in an exoneration. Moreover, research shows that eyewitness identifications tend to be less reliable when the person making the identification is of a different race than the person they are identifying, as was the case for Henry.

“I was mad and angry, not with the people around me, but at the system for what it had done to me,” said Henry. “Ask anybody at Angola about the ‘cat in the hat’ and they’ll tell you he just wants to clear his name and go home,” Henry said, using the nickname given to him by the men at Angola because he always wore a hat in the fields.

“I was mad and angry, not with the people around me, but at the system for what it had done to me.”

“I was mad and angry, not with the people around me, but at the system for what it had done to me.”

Henry James

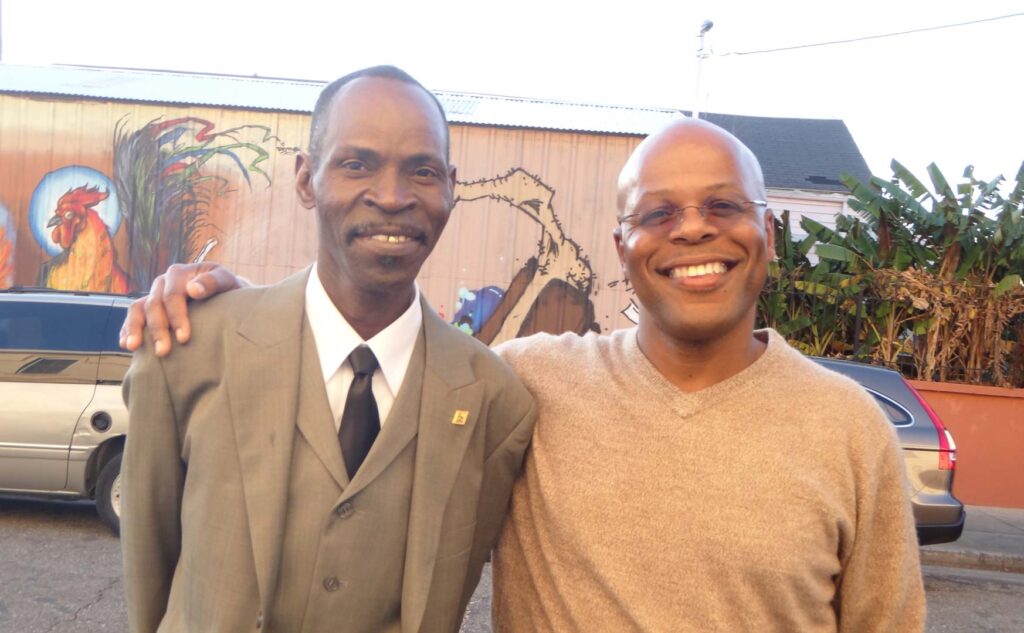

A prison guard oversees incarcerated people returning to the dorms from farm work detail at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, La., on Aug. 18, 2011. (Image: AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Picking cotton

Henry needed time and help. He couldn’t read or write well, and relied on a dictionary to look up words to write letters to lawyers and innocence organizations.

But, in his first couple of years at Angola, Henry didn’t get a lot of free time.

He worked hard in the fields to avoid being written up for a “work offense” yet frequently found himself being sent to “the dungeon” — otherwise known as solitary confinement. One guard in particular would see to it that Henry was sent to the “dungeon” as often as twice a week, citing ambiguous issues with his work.

“The dungeon was the last place I wanted to go because they wouldn’t even give you a pen and paper, never mind a law book. So, that was a setback in my plans to go home,” Henry said. Locked in solitary, he couldn’t make use of the prison’s law library or get help.

Time in the “dungeon” also meant more time working the fields. Almost all incarcerated people who arrive at Angola spend their first 90 days working in the fields. After 90 days without any “incidents,” people can apply to change jobs. But every time Henry was sent to the “dungeon” or written up on a “work offense,” the clock started over.

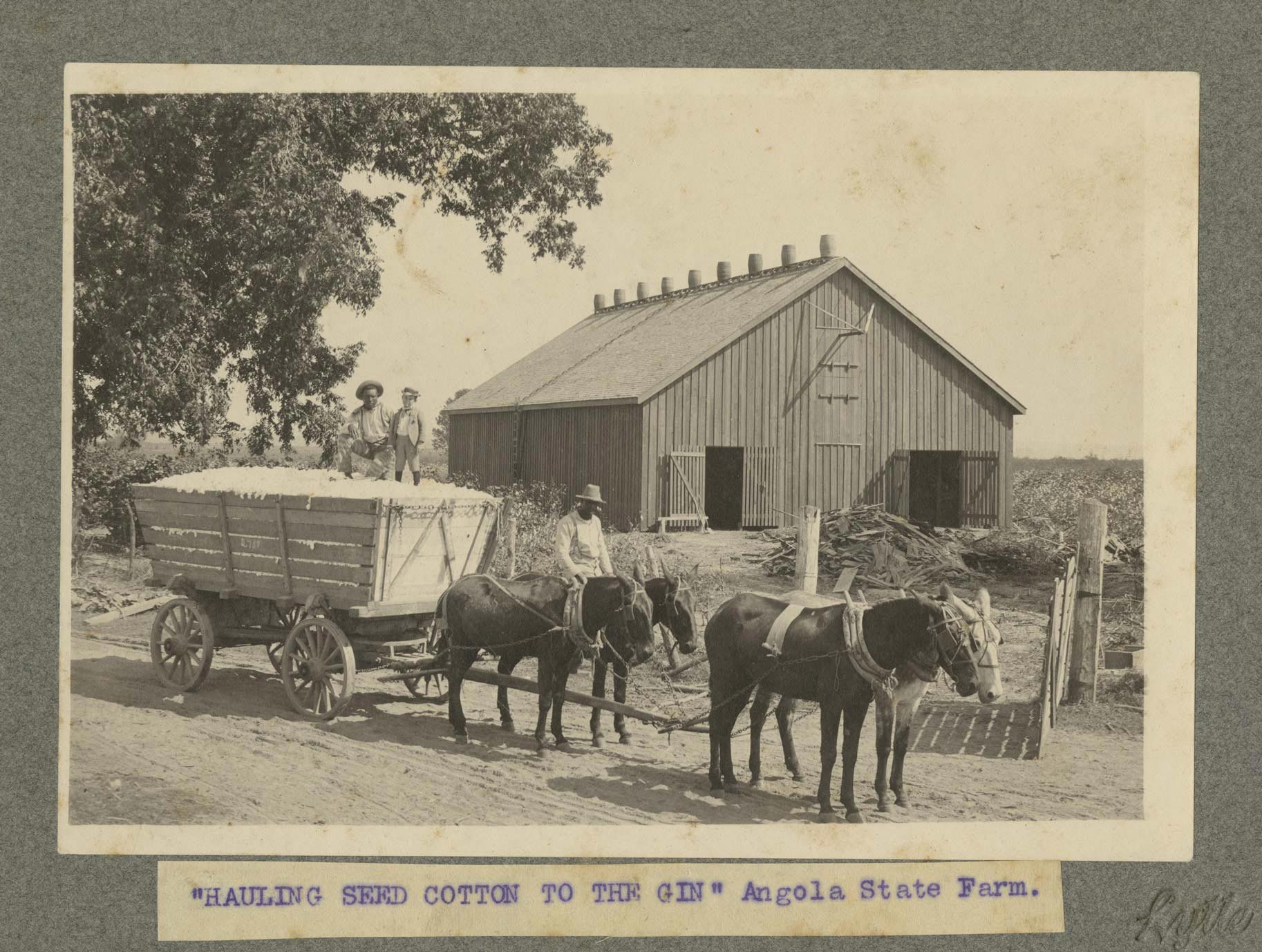

In total, Henry spent almost three years working in the fields — picking cotton, peas, okra, tomatoes, squashes, and turnips, cutting ditches, scraping grass off the levees on the same spot where just 100 years before slaves had done the same. He was paid 2 to 4 cents an hour.

“I would say I’m a professional cotton picker, I’ve picked so much. I would be picking sometimes and my hands would be so cold I could barely move ‘em, my fingers would be numb,” he remembered. “But I had to do it to earn the ‘privilege’ to do what I needed to help myself get out — that’s why I went through all that I went through and took all that I took.”

Henry and others also endured humiliation and poor treatment in the fields, where they were often deprived of water.

“When you would finally get to the water bucket — which was at the other end of the field — they would move it farther away. And if you stopped working to walk closer, you’d be written up for a work offense,” Henry recalled. “At the end of the day, they’d dump out the water bucket as you were getting there, and, if you say something, you get punished.”

The men would then have to walk back to the dorms, typically more than a 30-minute walk, Henry said.

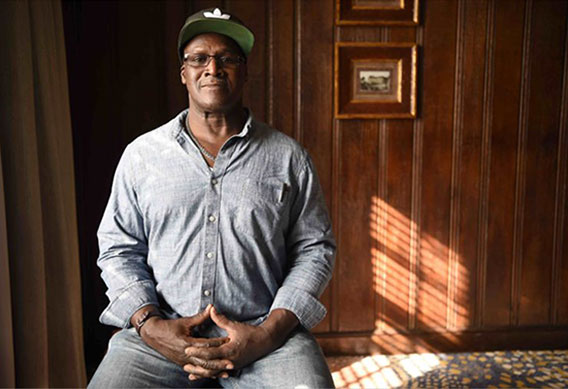

When Henry was finally approved for a job change and reassigned to work in the kitchen, he buckled down on his goal of clearing his name. He taught himself to read and write, using a dictionary, and even helped a few others learn. He spent time in the law library, where he met Calvin Duncan, another wrongly incarcerated person who worked as the prison’s “inmate counsel” (also called a jailhouse lawyer).

Henry James (left) and Calvin Duncan (right), who was also incarcerated at Angola, after Henry’s exoneration. (Image: Innocence Project)

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.