- “There was

- nothing and

- nobody”

She Wanted to Be a Mom. Wrongful Conviction Shattered Her Dream.

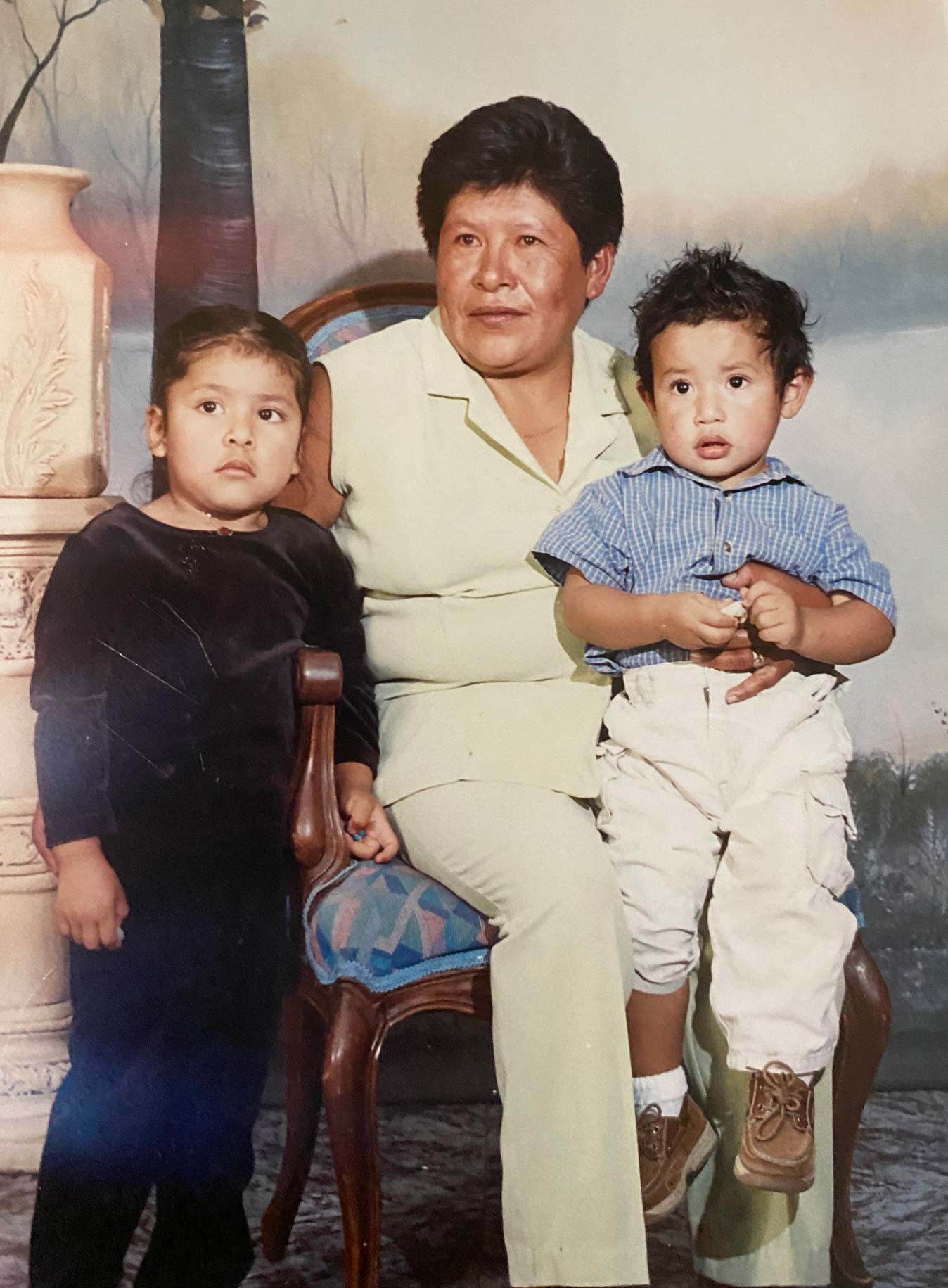

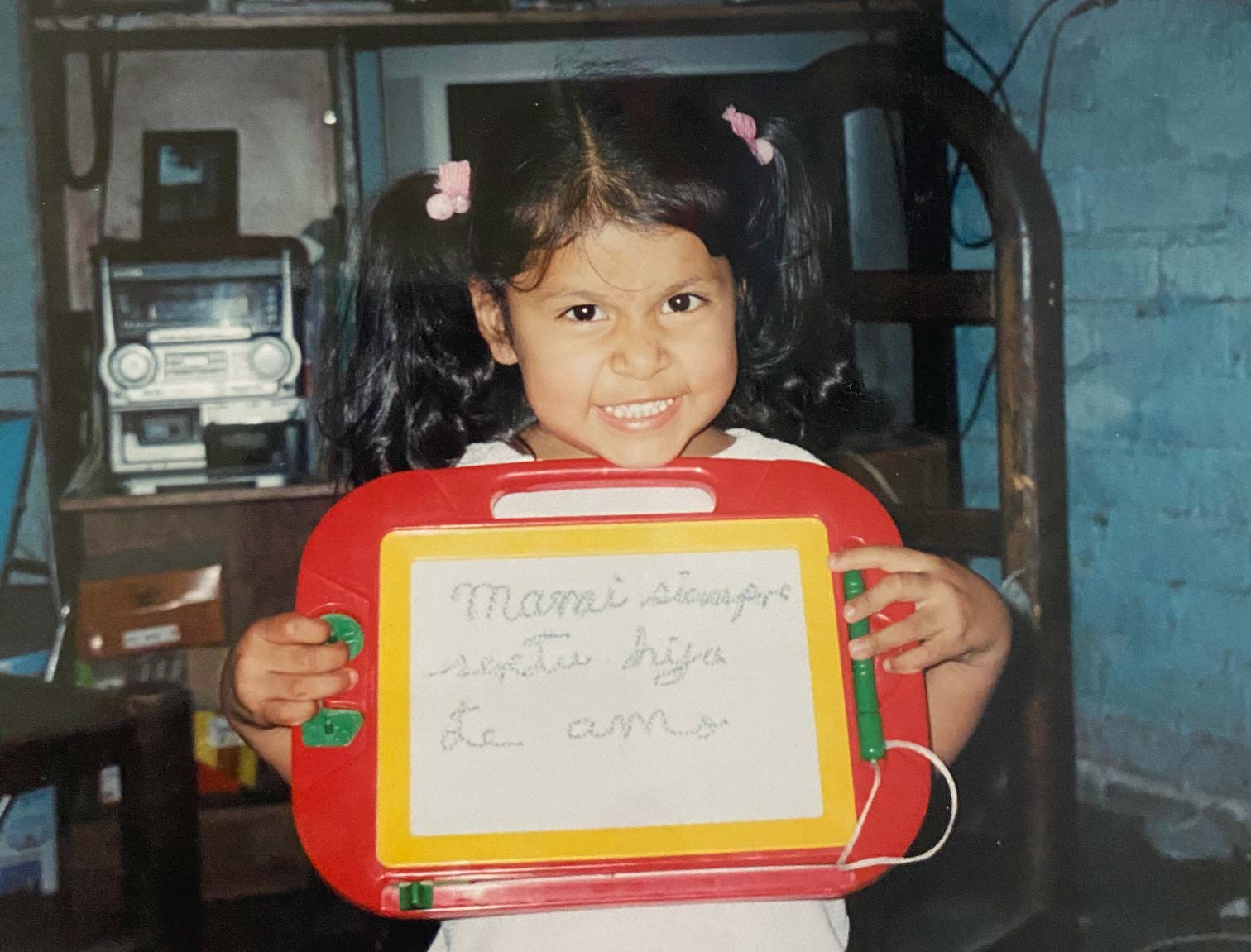

Rosa Jimenez was pregnant with her second child when she was arrested for a crime she didn’t commit.

Special Features 03.26.21 By Daniele Selby

“Emanuel.” Scared, alone, and very pregnant, Rosa Jimenez decided that’s what she would call her son, her second child.

She’d found the name in her Spanish Bible, one of the few things she had with her in the Travis County Jail in Austin, Texas, where she was awaiting trial for a crime that had never happened.

Emanuel means “God is with us.”

“I thought — okay. I’m going to name him Emanuel because I need to name him something that gives me hope and because I do believe that God will be with us,” Ms. Jimenez said. “I thought, now every time that I look at him, he’s gonna remind me that there is something more than just this place.”

“This place” — the county jail — was somehow more terrifying than the the last place — the Travis County Correctional Complex, where Ms. Jimenez had been sent first. But with her due date approaching, she had been sent to the smaller county jail which was closer to the hospital “in case something happened.”

But “something” had already happened.

Bryan Gutierrez, a 21-month-old who Ms. Jimenez regularly babysat and loved like her own, had died after a tragic accident, and Ms. Jimenez had been wrongly accused of killing him. Even worse, she would soon be wrongly convicted for his death and sentenced to 99 years in prison.

The “ugliest” time

“There was nothing and nobody” at the county jail, Ms. Jimenez remembered. “Just a little room with a bed, and nobody inside with me, nobody on one side or the other. Just me, by myself.”

Confused, close to giving birth, and now totally alone, she was even more afraid than she had been at the Travis County Correctional Complex, where the women incarcerated inside had pointed and jeered at her arrival.

“I couldn’t figure out what they were saying because I didn’t really speak English, but I could tell they were saying ugly, ugly things,” Ms. Jimenez remembered. “Some of them were yelling, they were hitting the windows … I thought they might kill me.” Like other women wrongly accused of harming children — including exonerees Hannah Overton and Kristine Bunch — the news had made her out to be a monster.

The harsh coverage of Ms. Jimenez’s case was not entirely unique. Crimes involving female suspects tend to receive more media spotlight than similar cases involving men, especially when the accusations against them involve children. Media coverage of women suspected of harming children often weaponizes gender stereotypes, painting women as “evil” or “bad mothers” and portraying them as having fallen short of the traditional gender roles of gentle and nurturing mothers. These biases can contribute to wrongful conviction.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.