The Case for ‘Blind’ Lineups

09.17.12

By Barry C. Scheck and Karen A. Newirth

(

Originally appeared in the

Los Angeles Times

.)

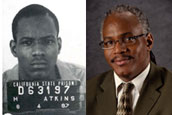

Photo: Herman Atkins, of California, was wrongfully convicted based, in part, on eyewitness misidentification and later exonerated through DNA testing.

Nearly 300 American men and women wrongly convicted of crimes have been exonerated by DNA testing. And in the bulk of those cases — almost 75% — the convictions were based in part on faulty eyewitness identifications.

Witnesses are often asked to identify suspects from photo lineups, which are typically conducted by the officers investigating a crime. But numerous scientific studies on memory and identification have demonstrated that witnesses can be influenced, intentionally or not, by the person conducting a lineup. An officer who believes one of the people in a photo lineup is the likely perpetrator can influence — sometimes without even meaning to — the proceeding.

This has led scientists to recommend “blind” lineups, meaning that the officer who conducts the lineup shouldn’t be aware of the identity of the suspect, so that he or she can’t contaminate the identification procedure.

Many cities, as well as many states, have embraced this approach. Los Angeles is not one of them. Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck refuses to embrace blind photo lineups. He told reporters that his reluctance was based on the belief that an officer close to the case would be more likely to have rapport with witnesses, and that this could produce better outcomes.

Beck’s reluctance should be allayed not just by scientific studies or the adoption of blind administration as a best practice by groups like the International Assn. of Chiefs of Police, but by more than a decade of success in the field, including statewide programs in New Jersey, North Carolina and Texas.

This newspaper recently reported on cases in which detectives seemed to consciously guide eyewitnesses to a police suspect during a photo lineup. One of the officers was later disciplined by the department for his actions. A requirement that the procedure be “blind” would prevent not just deliberate misconduct but also the more common problem of administrators inadvertently providing cues — sometimes nonverbal — that can influence witness choices.

In 2006, a California commission recommended that police in the state institute blind lineups, and initially the LAPD was on board. But then the L.A. County district attorney’s office said it opposed even doing a pilot program to field test the effectiveness of the new approach. “We prosecute thousands of cases,” a D.A. spokesman told The Times. “How many can you point to where it was shown that the police consciously or unconsciously influenced an eyewitness identification?”

The answer to this question is that we will never know, particularly when the influence can be subtle. What we do know with certainty is that California has seen nine people convicted of crimes later exonerated by DNA testing, and eight of those cases were attributable — at least in part — to eyewitness misidentification. The Northern California Innocence Project and the California Innocence Project report an additional 10 non-DNA exonerations that were attributable to misidentification.

DNA testing is rarely useful in overturning wrongful convictions because biological material that is instructive on guilt or innocence is available in less than 10% of criminal cases. While we cannot begin to guess the scope of the entire problem in California, we do have proof that 18 people spent years behind bars for crimes they didn’t commit after being misidentified. We also know that while they sat behind bars, the real perpetrators remained free to commit more crimes. The Innocence Project has identified the real perpetrator in more than 100 of its nearly 300 DNA exonerations nationwide. Those individuals went on to commit more than 70 rapes, 32 murders and countless other violent crimes while other men served their time.

The eyewitness identification reforms, which were recommended by the broadly constituted California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice, are cost-neutral. If an agency doesn’t have the manpower to get a second officer to administer the lineup, the officer can use a “folder shuffle system” in which photos are placed in individual folders and then shuffled by the chief investigator.

Some law enforcement leaders in California have already voluntarily implemented these modifications to identification procedures in their own agencies. Let’s hope Los Angeles follows soon. Making sure that innocent people don’t get put behind bars isn’t simply a matter of fairness and justice; it’s a matter of public safety.

Barry C. Scheck is the co-director and Karen A. Newirth is the eyewitness identification litigation fellow at the Innocence Project.

Read

Los Angeles Times

coverage of

LAPD lineup procedures

.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.