The Woman Behind Season One of Serial: Rabia Chaudry Releases New Book on the Untold Story of Adnan Syed and the Murder Case that Captivated Millions

08.12.16 By Carlita Salazar

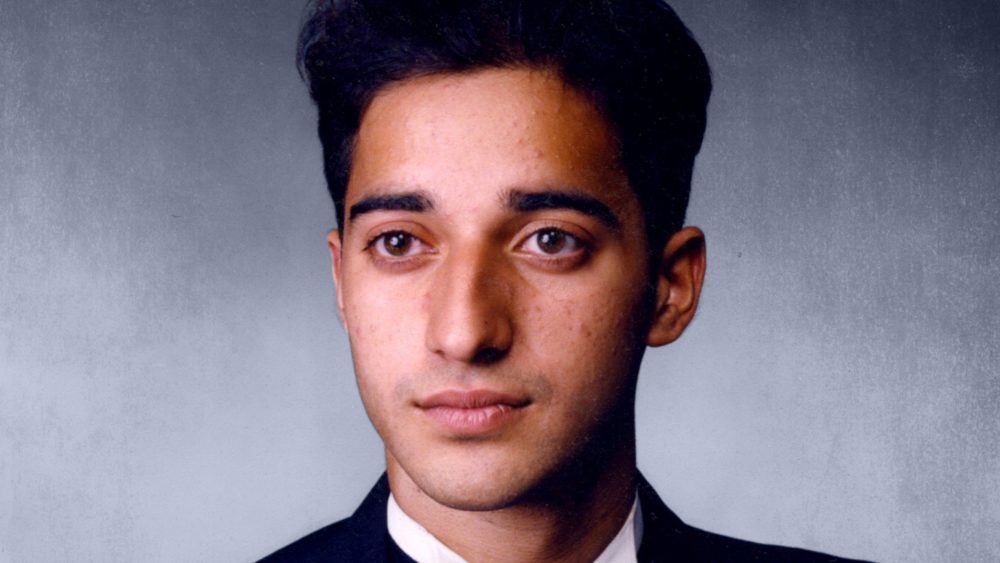

In 2014, attorney and writer Rabia Chaudry contacted producer Sarah Koenig at This American Life to pitch a story about the 1999 murder case of Maryland teenager Hae Min Lee. The result was Serial, one of the most successful podcast ever produced. The series—downloaded 100 million times—put Adnan Syed, the young man convicted of the 1999 murder, in the spotlight, and highlighted aspects of the investigation that Syed’s supporters, including Chaudry, say reveal his innocence.

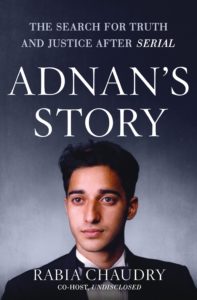

But Chaudry says that Serial didn’t tell the whole story. In response, she’s released Adnan’s Story: The Search for Truth and Justice After Serial, her new book which delves into important case details not covered in Serial. The book also includes written recollections and insights from Syed himself.

Earlier this week, Chaudry spoke with the Innocence Blog about her reasons for writing the book and how Serial got some of the story wrong.

Innocence Blog: You have been an incredible champion for Adnan. Did you ever think, back in 2000 when he was convicted, that you would eventually play such an important role in his case?

Rabia Chaudry: Absolutely not. I was in law school [when the case started]. I had no experience in criminal law—not then, not even now really. The thing that I hoped to do, after the conviction especially, was help the family select good attorneys.

I really had a lot of confidence in the system—that there had been a tremendous mistake. Especially after Cristina Gutierrez (Adnan’s trial attorney) was disbarred and became ill. I thought: “The Maryland judiciary system knows—everybody knows—what she went through and how that must have affected her clients.” There was a part of me that thought, “How could those cases that she had in her last couple of years not be given a little more attention to see what really went wrong?”

But I never imagined that it would be like this. And I didn’t want it to be like this. I wanted the system to work. It’s ridiculous that it would take this long. And it’s crazy that it would take so much media and so many resources and investigators to correct something like this.

IB: Knowing all of the information that was out there—with Serial, with your podcast Undisclosed and your blog—what then spurred the book?

RC: Actually, it started before the Undisclosed podcast even began. When Serial was airing I was blogging every week in response to it. And I had been writing for many years for different outlets and across a spectrum of issues—a lot of political issues and issues around bigotry and civil rights. There was a literary agent who read my blog and had seen my other writing and said, “You should consider writing a book.” And I said, “Oh, that would be great. I’d love to write a book. I’ve always wanted to write a novel.” And she said, “No, I mean about Adnan’s case.”

I had never considered it. It was overwhelming. I didn’t know the case as well as I needed to, even at that point. The case documents—I hadn’t seen them in many, many years. They had gone from Adnan’s home to Sarah Koenig. And she had given me an electronic copy once, but for me to have my daily full-time job, plus my family, plus a blog—I didn’t have the time to go through the documents.

So when the agent contacted me, I said, “Absolutely not. I can’t do it. And, it would feel a little exploitive. I’m not comfortable with that.” But then she raised an excellent point.

She told me that somebody was eventually going to write the book. It could be me—someone who knows Adnan, knows the lawyers, knows Sarah Koenig, knows more about the story than anyone could know, and who also is very concerned about protecting Adnan’s interest. Or, it could be another journalist. “It’s your choice,” she said. So, I talked to Adnan about it and told him that she made a good argument. He told me that if I wanted to do it, I had his permission.

I ended up writing 800 pages in eight months. I had plenty to say. There were a lot of materials to draw from. There were all of the blogs that I’d already written. There are the case files, the police files, there’s Serial. There’s so much content. It was actually hard to cut it down.

IB: Without giving too much away, what new information do you think that people will take away from the book?

RC: It depends. There are people who know nothing about the case at all. They’ve heard of Serial but they have no idea what it’s about. There are people who listened to Serial but have no idea what happened afterwards. Then you have the people who are really deep in the weeds—they know everything about the case. The book has something for everyone.

Definitely for people who know nothing about the case, I document everything about the investigation—step-by-step what happened.

For people who listened to Serial, which I think is going to be our biggest audience, they’re going to learn a lot about the backstory, first of all, about why we had concerns about Serial, about where we disagreed with Sarah Koenig and about many things that the series either missed or just got wrong. And also about why Adnan’s conviction was vacated.

Also, I think there was a false narrative that has existed since Serial that I wanted to dispel in the book—the idea that Adnan doesn’t remember his day [in 1999 when Hae Min Lee went missing]. What truly happened was Adnan was made to think that he didn’t remember that day. He was told, “What you’re remembering is wrong.” I really wanted to dispel that idea and show how many times in the notes he brought up Asia McClain to his attorneys, how he wrote out a timeline of his day.

But another thing that people will get—even those people who are deep in the woods [with the case]—are the letters that Adnan has written over the years. There are letters from after he was arrested to after he was convicted to after he got married. And then there are his own contributions to the book. So even people who have listened to every little detail that we’ve discussed on Undisclosed—they’re not going to have come across this content before.

IB: In your book, you write about the prosecution’s case being heavily influenced by racial and religious bias. Why do you think it was so difficult for Sarah Koenig to believe that biases influenced Adnan’s case? Do you think that the issue is literally too “black and white” for some people to see that bias extends to many other types of groups?

RC: There are a few reasons. One is, I think when you are not a member of that group, you don’t get it.

When Serial aired, so many Muslims and South Asians—all kinds of South Asians: Indians, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs—contacted me and said, “Oh my god! This is so bigoted.” They knew what it was like to be that South Asian teenager. They said, “This is totally normal behavior. This is how all of us were.” So we all immediately sense it and get it.

Overall, society tends to privilege certain institutions, whether it’s judiciary or attorneys or police. I think that Sarah said on Serial that the detectives were basically just good guys trying to do their jobs. I thought, “That is an interesting conclusion given that there are misconduct cases against some of them.” But I think that she really believes that. In her mind, these are the white hats.

In the first trial, and this is later in the book, the judge said to Gutierrez, “I understand that the defendant’s religion plays a part in this case.” I don’t know how much more clear it can get [that bias played a role]. I have raised my case as strongly as possible that [bias] was a factor and that if it hadn’t been a factor, the state wouldn’t have kept bringing it up.

There’s also another reason that I want to articulate: I think there’s a part of Sarah that wonders if what the state was saying wasn’t true. I think she wondered, “Well, isn’t honor killing a thing for Muslims?” We’ve had those really weird conversations where I had to say to Sarah, “What are you saying?” So, I think there was something with her not knowing anyone from the Muslim community—not knowing that what was being said [in relation to Adnan’s region and the case] that was complete wacko B.S. and completely untrue. And that might have been why she wasn’t exploring the issue of bias, because she wasn’t sure if maybe some of it was true.

“. . . I didn’t want it to be like this. I wanted the system to work.” Rabia Chaudry

IB: What can Adnan’s case teach people about our country’s criminal justice system?

RC: You know, one of the most frustrating moments of Serial for me was when one of the producers said that Adnan had to have been the unluckiest guys in the world. And I thought, “No, because this happens all of the time.” It takes every part of the system to fail in order to get a wrongful conviction. The state got it wrong, the police got it wrong, the defense didn’t do their job. Everybody failed that defendant. Obviously, [wrongfully convicted people] are unlucky that it happened to them, but the way that it was said in Serial was that it’s so unlikely that anyone would be so unlucky. But it’s not that unlikely.

When Adnan was convicted, many of the people who hadn’t been in the courtroom—students he went to school with and grew up with and other people in the community—they couldn’t attend the trial. So, in their heads, they believe, “Well, if he was convicted, there must have been solid evidence. There must have been DNA or something.” But that’s not how it works.

People are also learning about how difficult it is to undo these types of decisions when they happen. Turning it back is so impossible. And there’s such little accountability in the system. If I want to drive something home over and over again when I speak about the case to different audiences, it’s that we’re going to continue to experience these problems if police are not held accountable when they’re killing people on video, when prosecutors—over and over and over—are found to withheld evidence and they end up becoming judges. There should be some measure of accountability. You shouldn’t be able to ruin people’s lives and hold on to your position.

Find Adnan’s Story: The Search for Truth and Justice After Serial here: adnanstory.com

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

October 14, 2017 at 1:07 am

February 12, 2017 at 3:20 am

Is it true that Adnan Syed has refused to agree to DNA testing? His own or that of crime scene evidence? What is the reasoning behind this? Has there been recent interaction with The Innocence Project?

Why dont you get the DNA tested? Is it because you know it will come back as Adnan’s? If you dont get it tested, it makes it seem like you are hiding. Adnan is especially guilty of this seeing that he did not agree to it being tested.