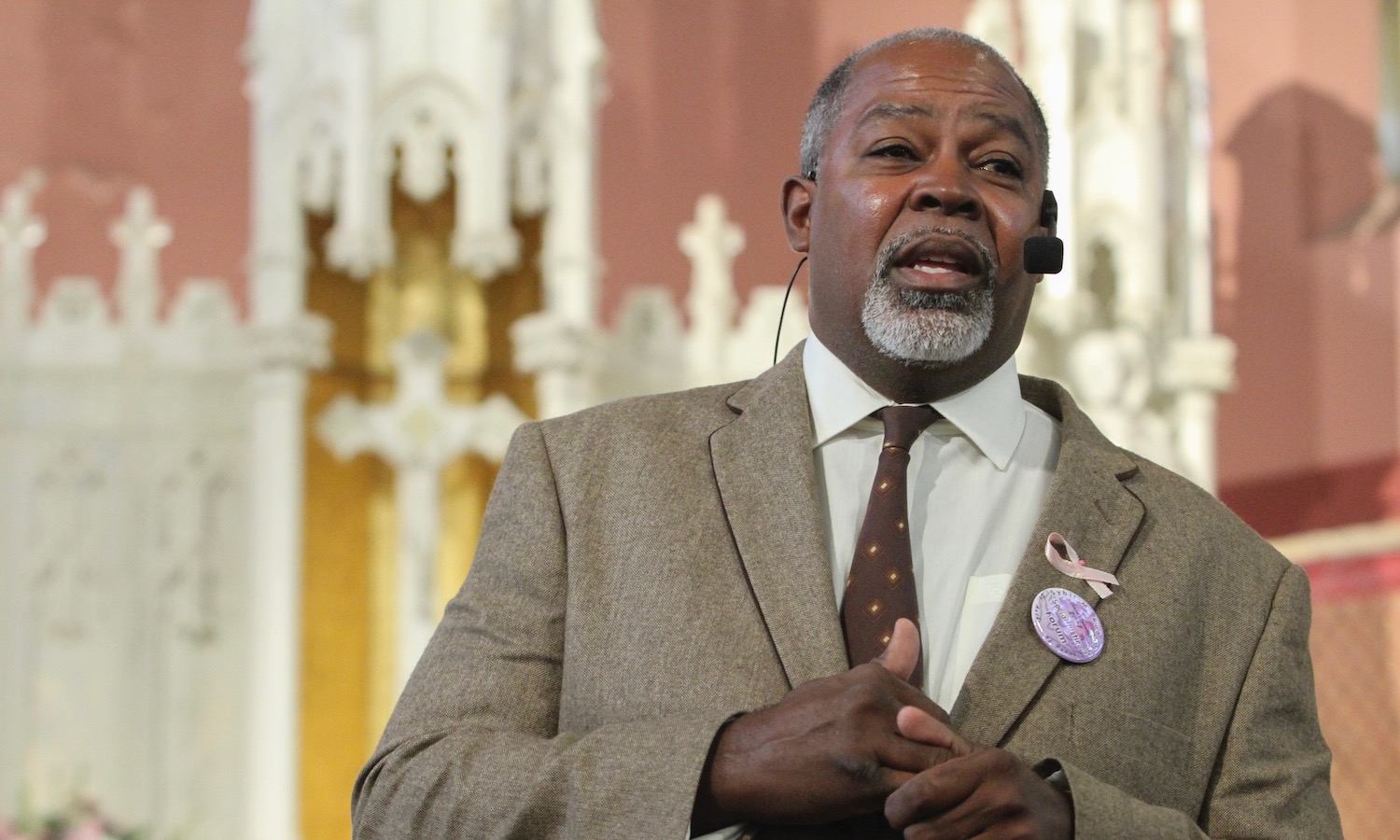

Calvin Johnson reflects on his journey from wrongful conviction to advocate and Innocence Project board member on the occasion of the organization’s 25th anniversary in 2017.

In Memoriam: Innocence Project Founding Board Member and Exoneree Calvin Johnson

The Innocence Project mourns the passing of Mr. Johnson, who played a critical role in guiding the organization's work.

01.25.23 By Innocence Staff

Calvin Johnson was an author, activist, a pioneer among the innocence movement, and a friend to many at the Innocence Project and in the broader Innocence Network. His death leaves a void that will be felt throughout the entire community.

In 1983, Mr. Johnson was wrongfully convicted in Georgia and sentenced to life in prison by an all-white jury. But, in 1999, after spending 16 years fighting for his freedom, he was proven innocent through DNA evidence and regained his freedom.

As soon as Mr. Johnson was exonerated, he became a voice for the voiceless — a fierce and committed advocate for other individuals who had suffered the grave injustice of wrongful conviction.

A Tireless Advocate for Criminal Justice Reform

Mr. Johnson took on a pivotal role at the Innocence Project: founding board member. For eight years, he served on the board with wisdom, unique insight, and heart, and was instrumental in helping make the organization what it is today. He also remained involved as a member of the organization’s Founders’ Circle. He was an inspiration, guide, and friend to many of the hundreds of exonerated men and women who were freed after him and an advisor to many who work in the Innocence Network.

Mr. Johnson’s insight laid the foundation for exonerated people to play a more critical and active role in shaping and guiding the work of the Innocence Project. When he was interviewed in 2017 about his work as an Innocence Project board member, he said, “I shared my insight and my viewpoint. I shared my true feelings — from my heart. Even though the board members were so knowledgeable, I offered an insider’s point of view. I think they felt what I went through from my words, my thoughts and my heart. It made a positive difference. And it made people want to make real changes.”

In 2002, Mr. Johnson was photographed by renowned photographer Taryn Simon for her book The Innocents. In the striking photo, he is featured standing next to his father on the front lawn of the family’s home in Georgia. This past May, Mr. Johnson told a personal story at a live event hosted at MoMA PS1, celebrating a new edition of The Innocents. In his story, he reflected on what he saw 20 years later when he looked at the photo in which he’s featured.

In addition to his work with the Innocence Project, Mr. Johnson served on the board, including as chair, of the Georgia Innocence Project. In September 2003, his book Exit To Freedom was published by the University of Georgia Press. Co-authored by Dr. Greg Hampikian, the book chronicles Mr. Johnson’s wrongful arrest, conviction, imprisonment, and the events that led to his exoneration.

Mr. Johnson, whose photos and case history are presented in Taryn Simon’s ‘The Innocents,’ reflects on what he sees 20 years later when he looks at the photo in which he’s featured at an event hosted by MoMA PS1.

In His Own Words

“If I could wave my magic wand, I’d make it possible for innocent people to be released from prison as soon as DNA tests cleared their names. Currently, the criminal justice system is so slow in allowing innocent people to walk out of prison. In my own case, I wrote to the Innocence Project in 1996. It was three years before I got out. Even when the evidence came back in November of 1998, I wasn’t exonerated until June of 1999. The sooner that a man or woman can walk out the better. So, as soon as the DNA tests would come in, I’d wave my wand — BAAM! — that person walks out of prison. And not just that, but — BAAM! Here’s some money. BAAM! Here’s a job. BAAM! Here’s a place to stay. I’d just keep on waving my wand.”

— Calvin Johnson

From Innocence Project Co-founder and Special Counsel Peter J. Neufeld

My first face-to-face encounter with Calvin Johnson was on June 15, 1999. We had filed a motion to vacate his conviction after the DNA testing proved that someone other than Calvin had committed the rape, for which he had already served 16 years of a life sentence. The court set it down for a hearing on the motion. I flew to Atlanta with Jim Dwyer, a reporter for the New York Times.

Up until the 15th, we had talked on the phone once every week for the previous eight months. I had read Calvin’s trial transcript and was taken by the words he spoke at sentencing: “With God as my witness, I have been falsely accused of these crimes. I did not commit them. I’m an innocent man.” I learned through our weekly conversations that his principled refusal to sign a statement in prison accepting responsibility for the rape he did not commit, meant that he would never be granted parole. The same prosecutor, who had thoroughly exploited racial bias and Jim Crow tropes at the trial in 1983 to secure a guilty verdict from an all-white jury, was still in office. But even he accepted the irrefutable evidence of innocence and was prepared not to oppose Calvin’s exoneration.

On that same day in June, I met Calvin’s adoring sisters, Tara and Judith, and his firm and loving father Calvin Sr. Once the conviction was thrown out, Calvin surrendered his orange prison jumpsuit for street clothes, strode out the courthouse doors and without any preparation, charmed the throng of reporters, declining to say anything negative about the people responsible for stealing 16 years of his life. We all piled into cars and drove to the hospital where Calvin’s mother, suffering a long-term illness, waited expectantly to greet her son. I stood safely on the perimeter of this emotional reunion, privileged to observe the workings of a very close and supportive family.

Within two weeks of freedom, Calvin was making trips to numerous churches in the South and the Caribbean preaching the gospel of wrongful convictions and the elimination of injustice. In September, he visited the Innocence Project’s offices in New York and signed up to do public speaking across the country to advance the project’s mission. Audiences could not help but be moved by his insights and inspiration. Our policy department channeled his unique skills for making even our most staunch adversaries comfortable with our criminal legal system reforms. He testified before legislative committees and met with and won over many government leaders. Over the next 20 years, he mentored dozens of exonerees challenged by the unfair obstacles to re-entry. He was a distinguished member of the Innocence Project’s inaugural board of directors. His wise counsel was sought and followed. In later years, when I visited Atlanta or Calvin traveled to New York, we met socially, over coffee, a beer, or a meal. We talked about family, spirituality, and morality as well as the state of the world.

In the beginning, Calvin was our client. His struggles inspired all of us. He quickly became our advocate, mentor, and bestower of wisdom. At the end, he was our dearest friend.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.