DNA’s Revolutionary Role in Freeing the Innocent

Celebrating World DNA Day: The History of DNA and its Unique Role in Proving Innocence

Special Feature 04.18.18

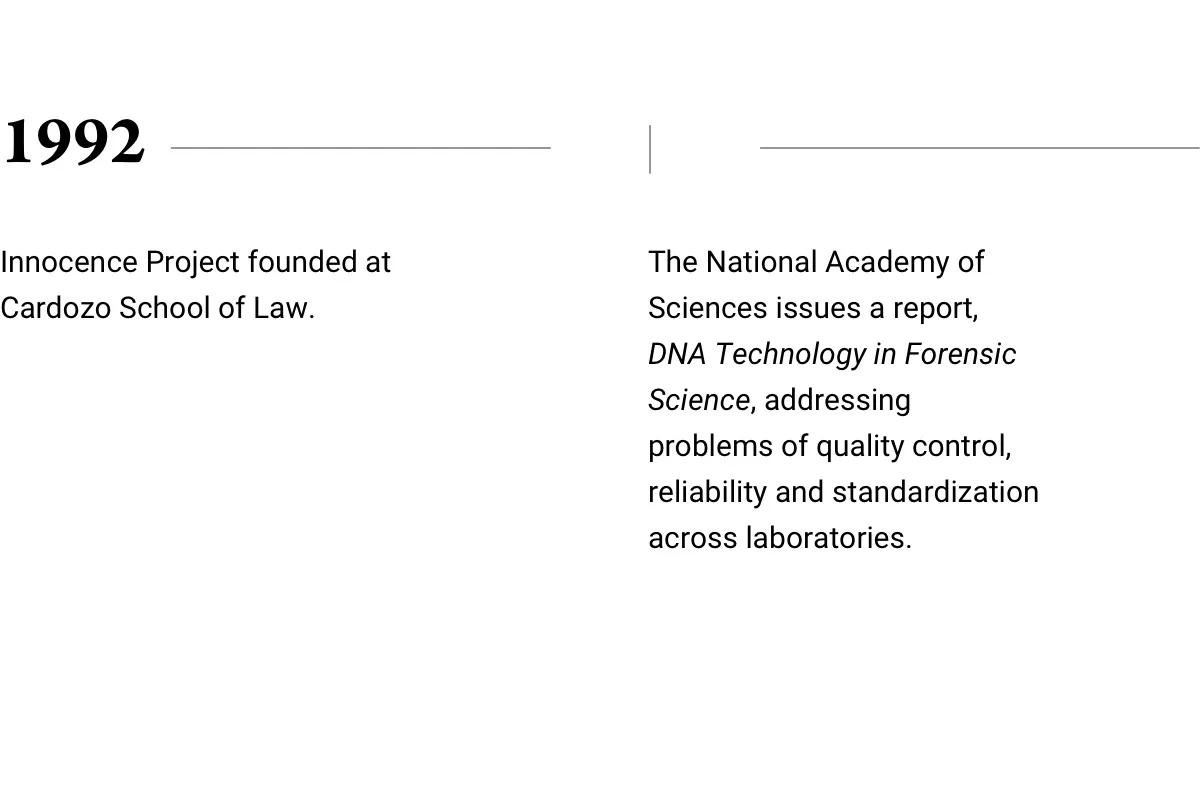

In 1992, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld started the Innocence Project as a legal clinic at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. The idea was simple: if DNA technology could prove people guilty of crimes, it could also prove that people who had been wrongfully convicted were innocent.

Research shows that 99.9% of human DNA is identical, but that .1% can be used in forensic labs to differentiate one individual from another.

In 1984, British Geneticist Alec Jeffreys was the first person to use DNA profiles or “DNA fingerprint tests” that are now used around the world to resolve questions of paternity and solve crimes.

As DNA testing was first starting to be used in criminal cases, Scheck, Neufeld, and their team of students at Cardozo Law School attempted to use DNA testing in seeking to reverse the conviction of Marion Coakley, a Bronx man who had been convicted of rape and robbery. The DNA tests were inconclusive, and the team was eventually able to prove Coakley innocent through other means. But through working on Coakley’s case, Scheck and Neufeld realized the potential of DNA technology to reverse wrongful convictions.

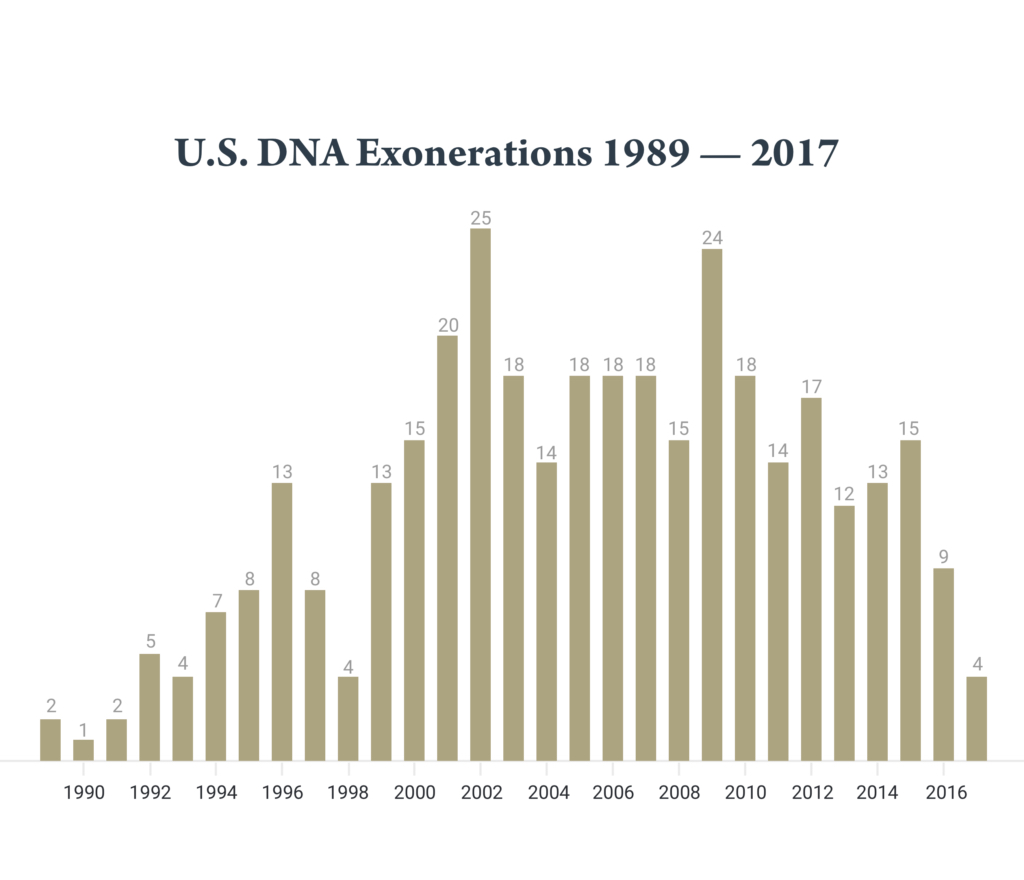

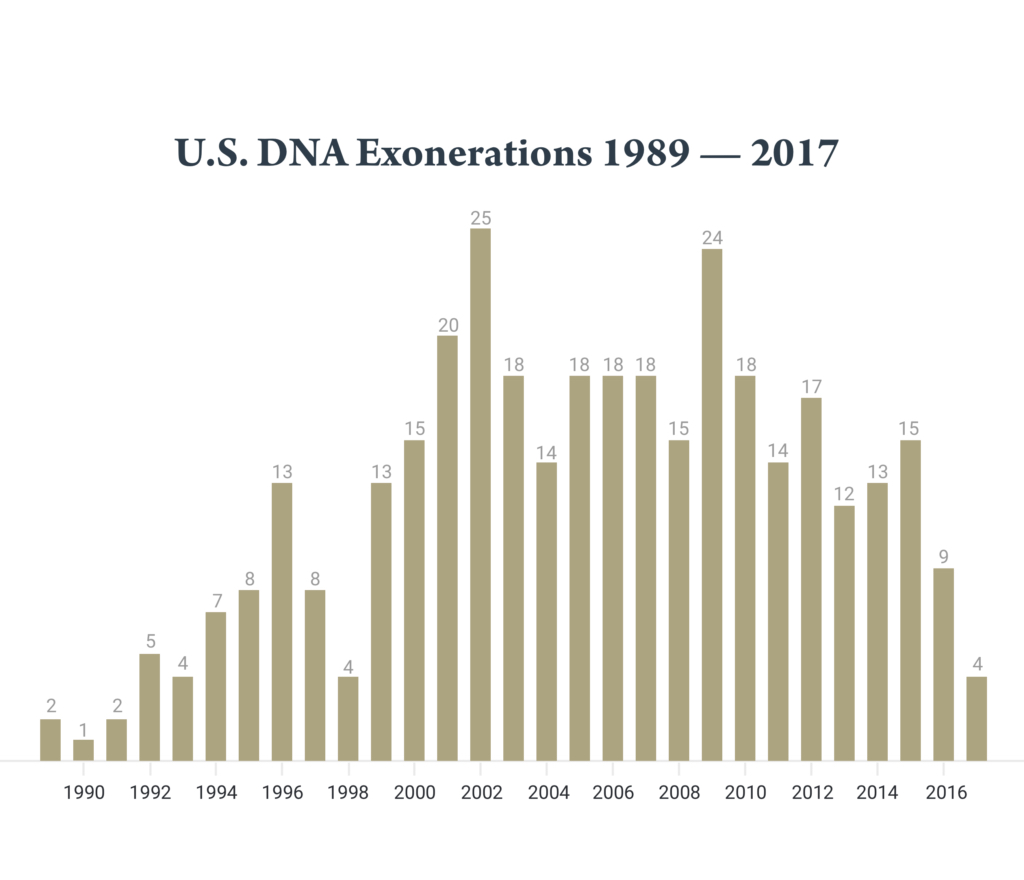

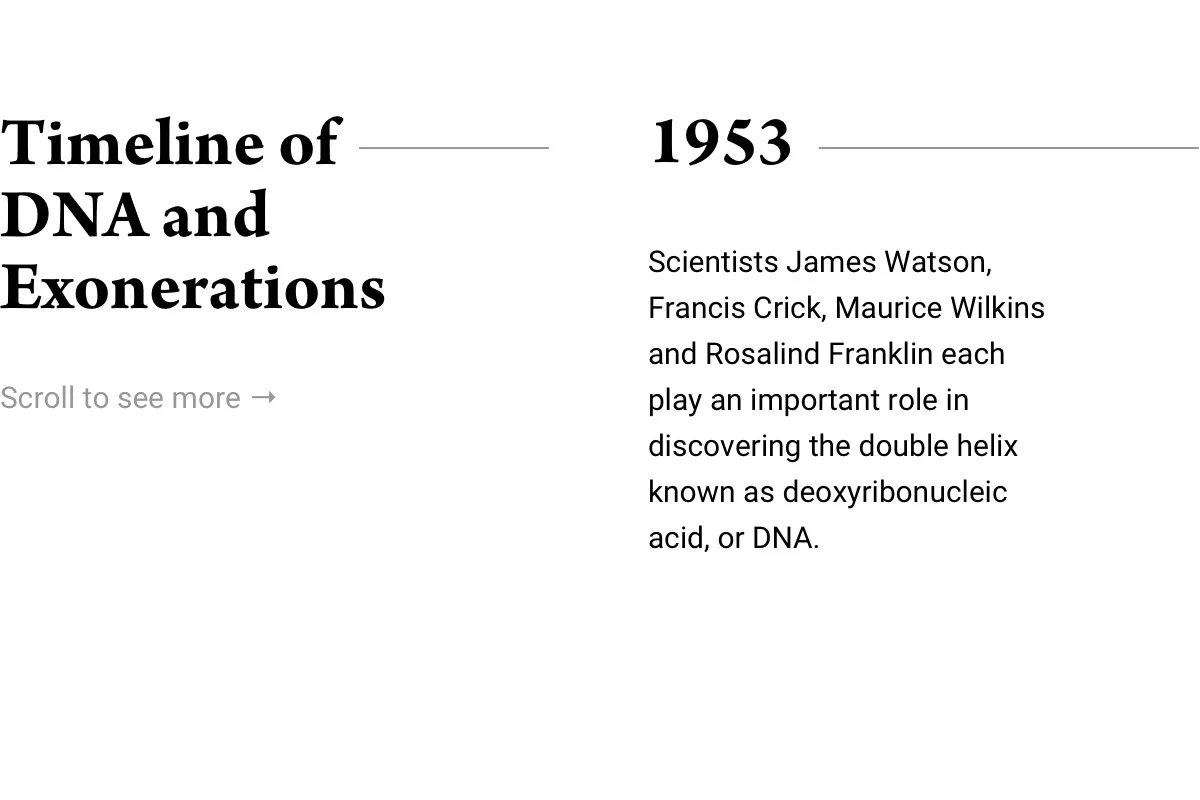

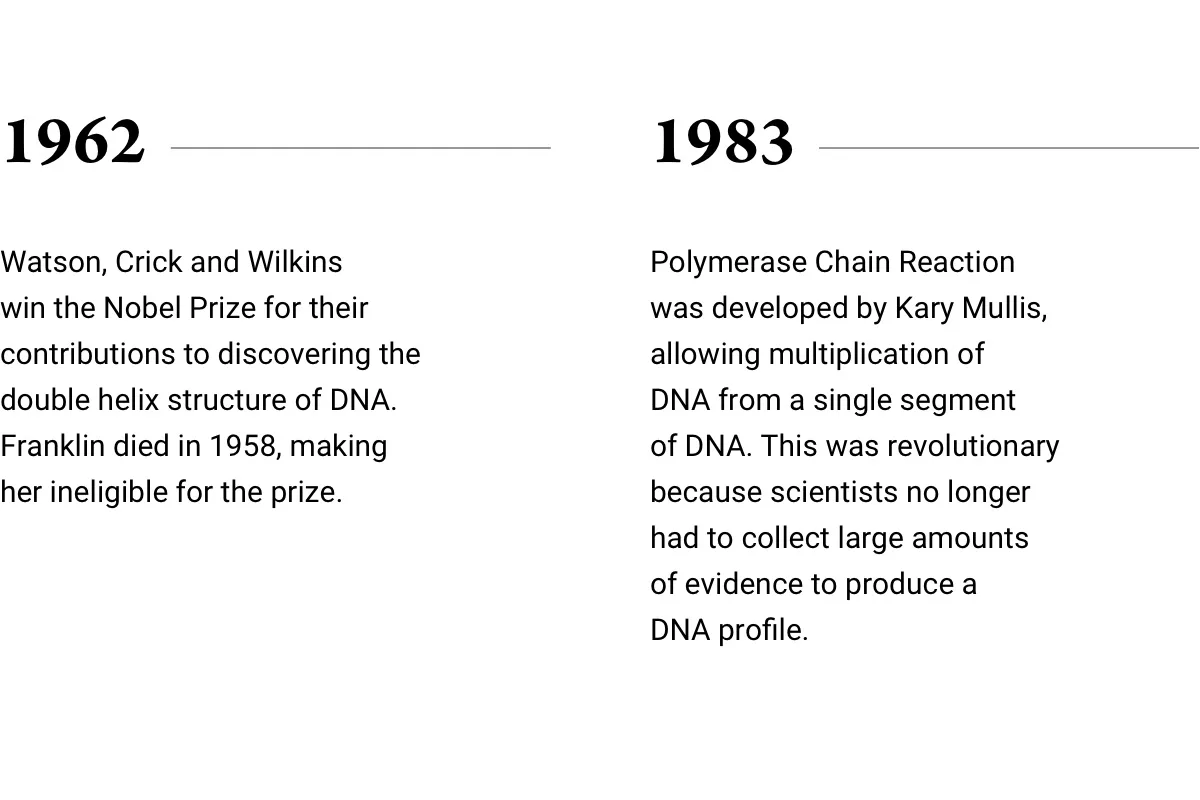

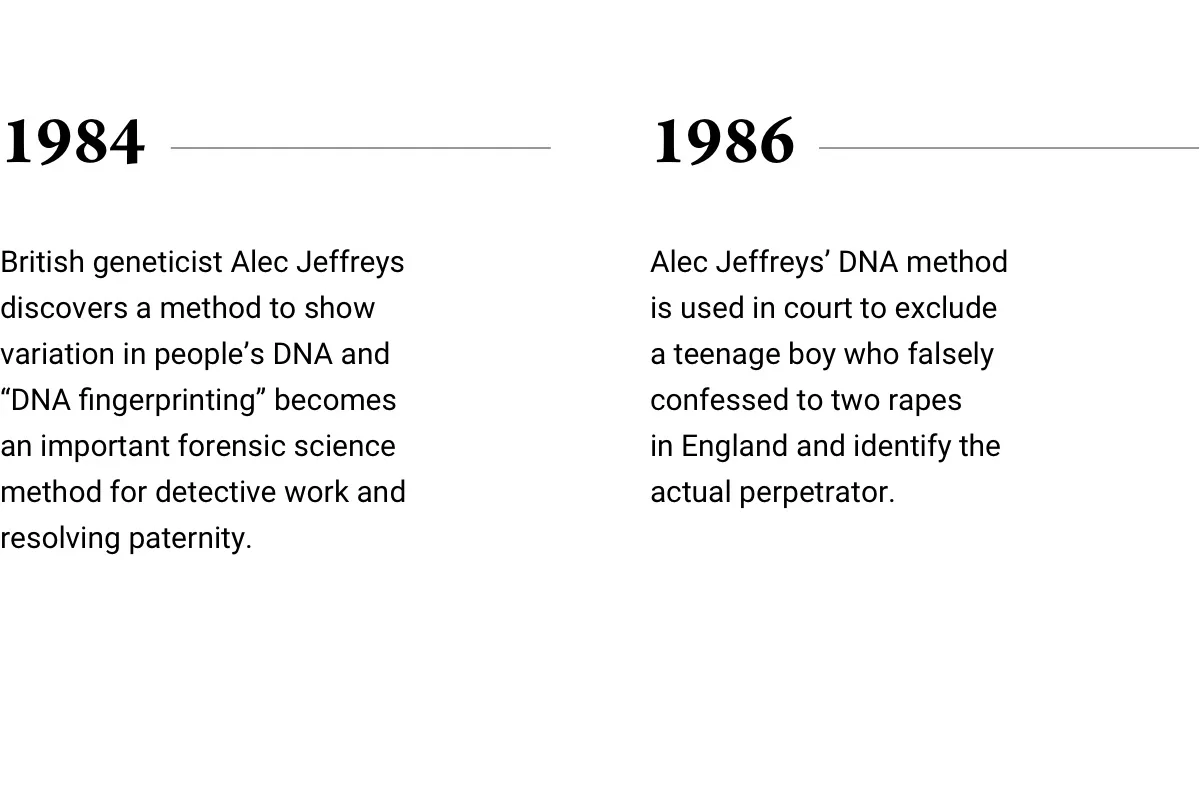

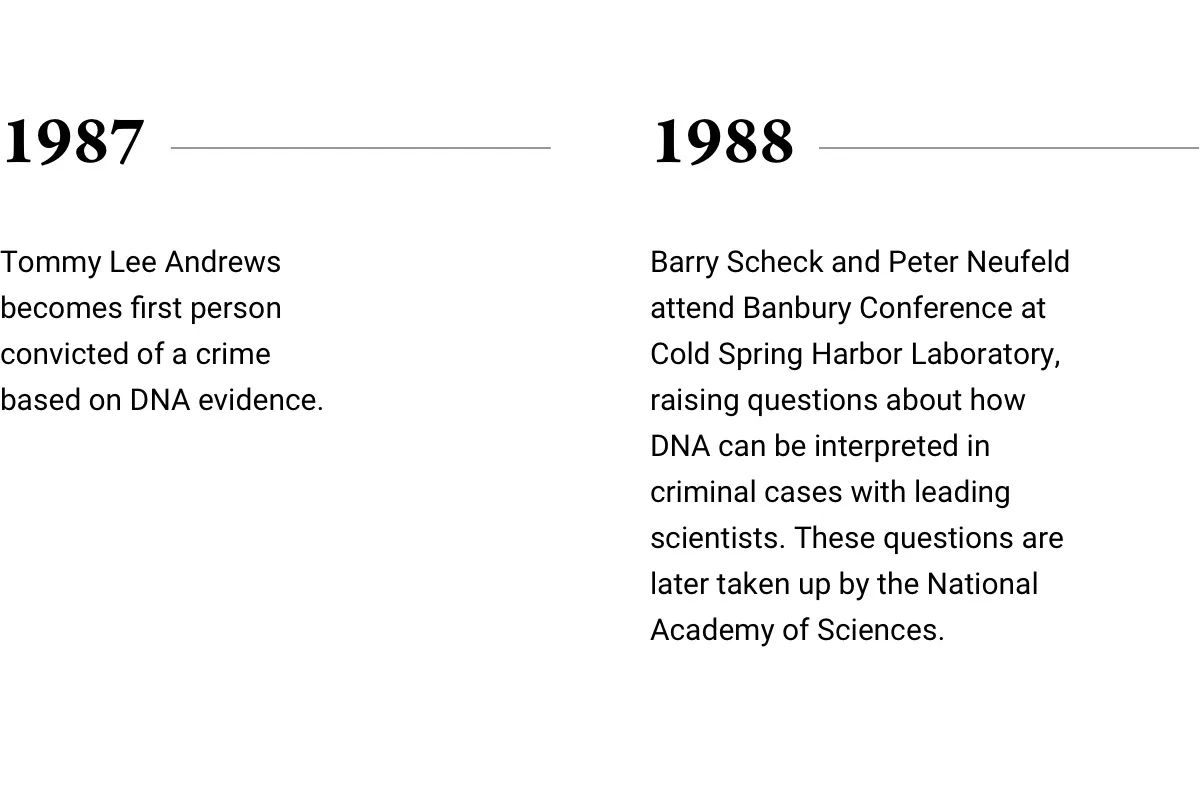

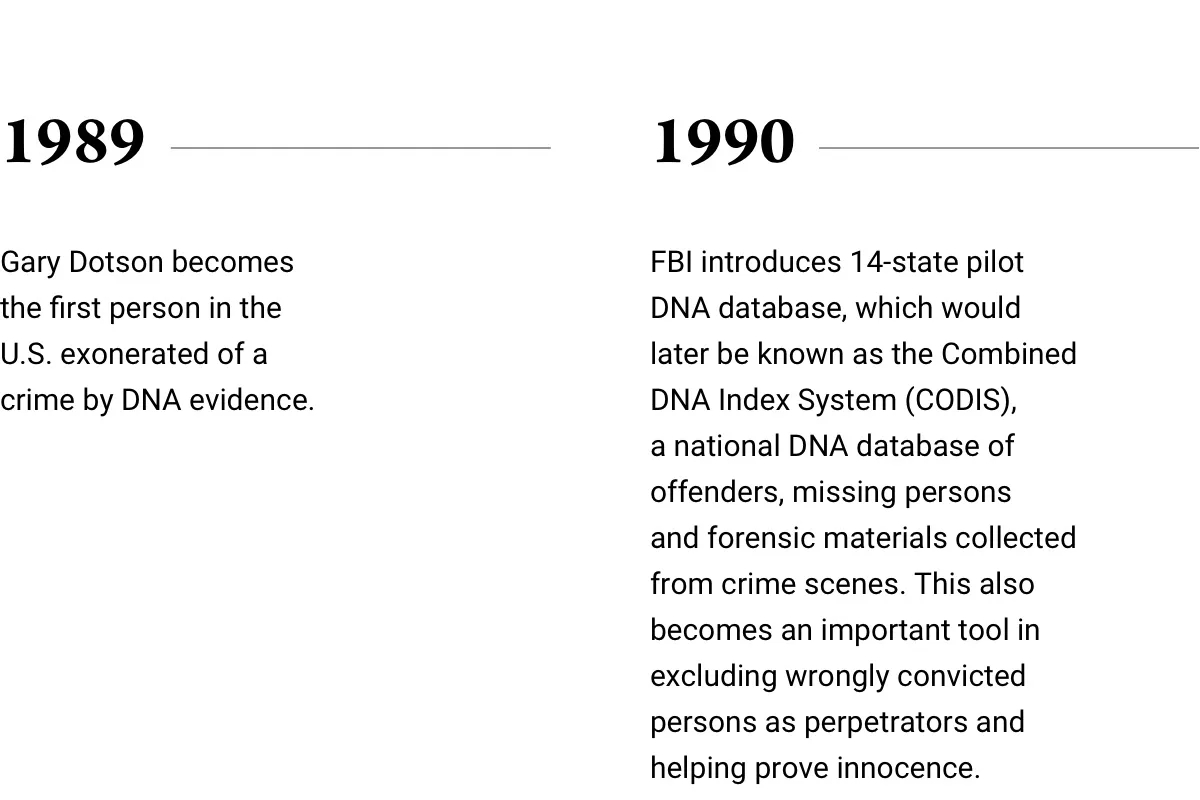

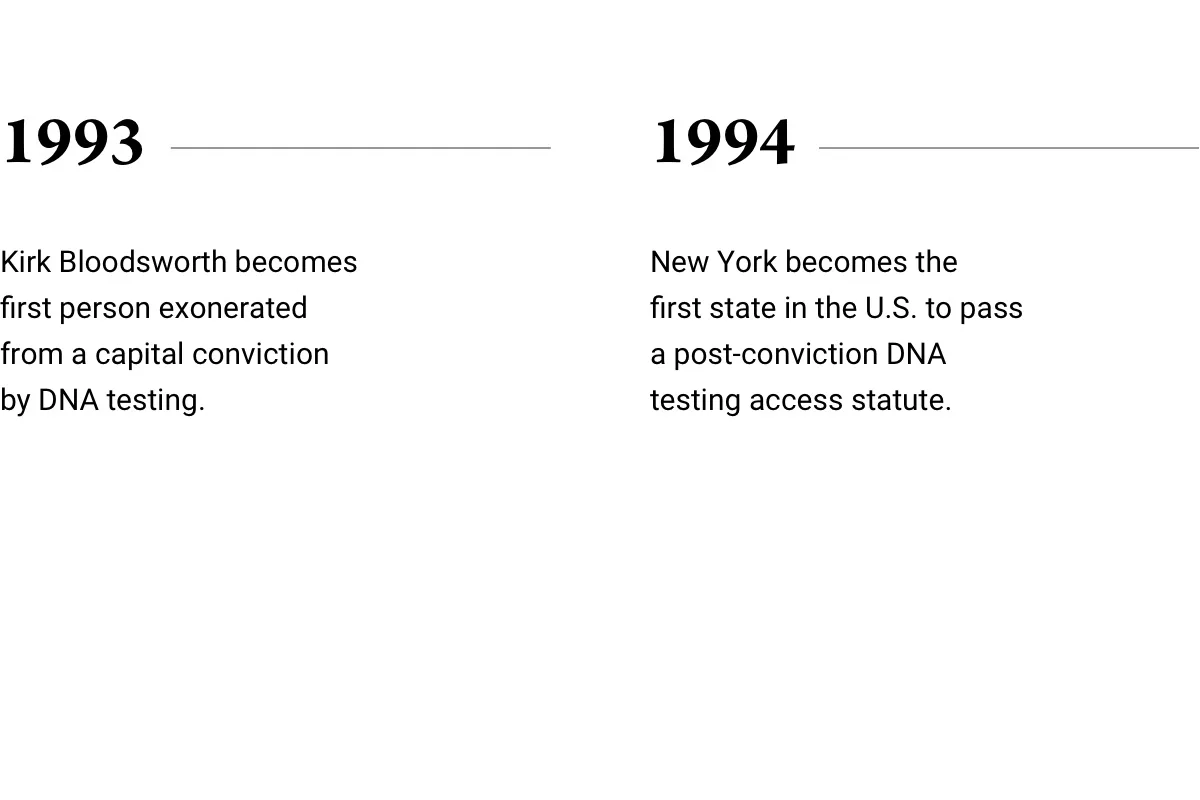

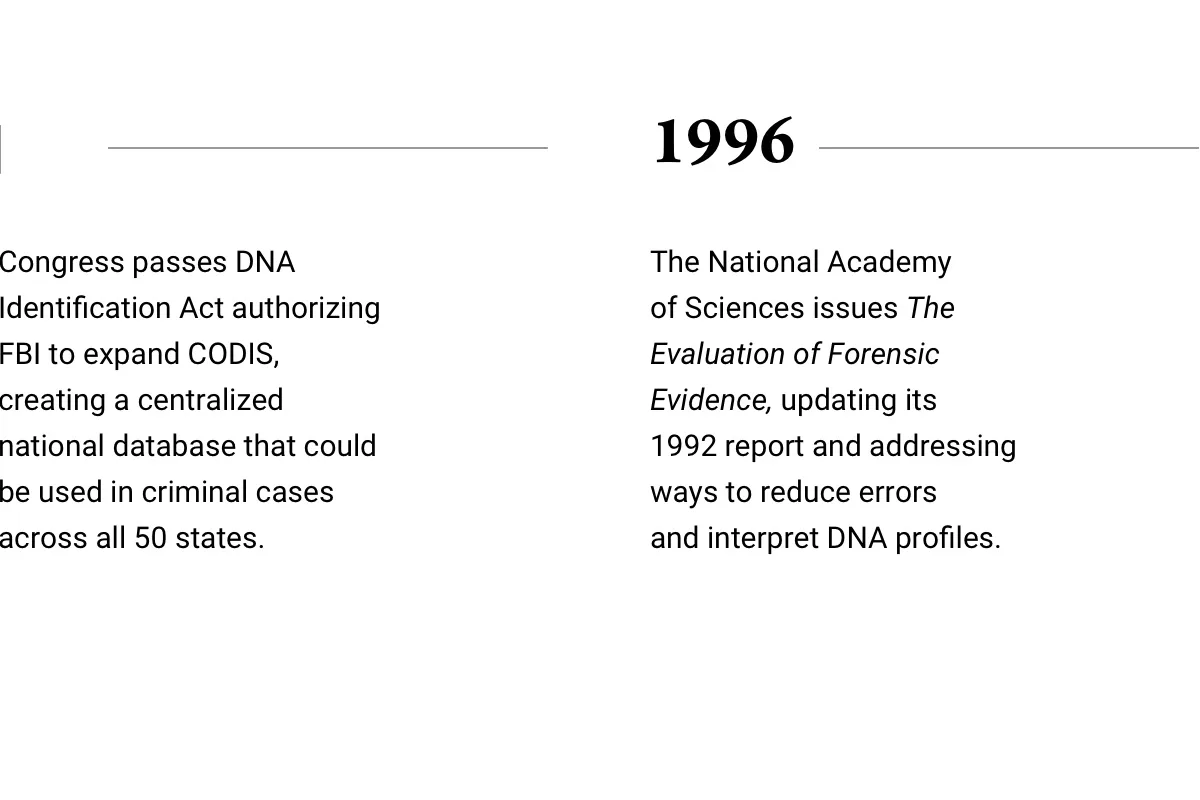

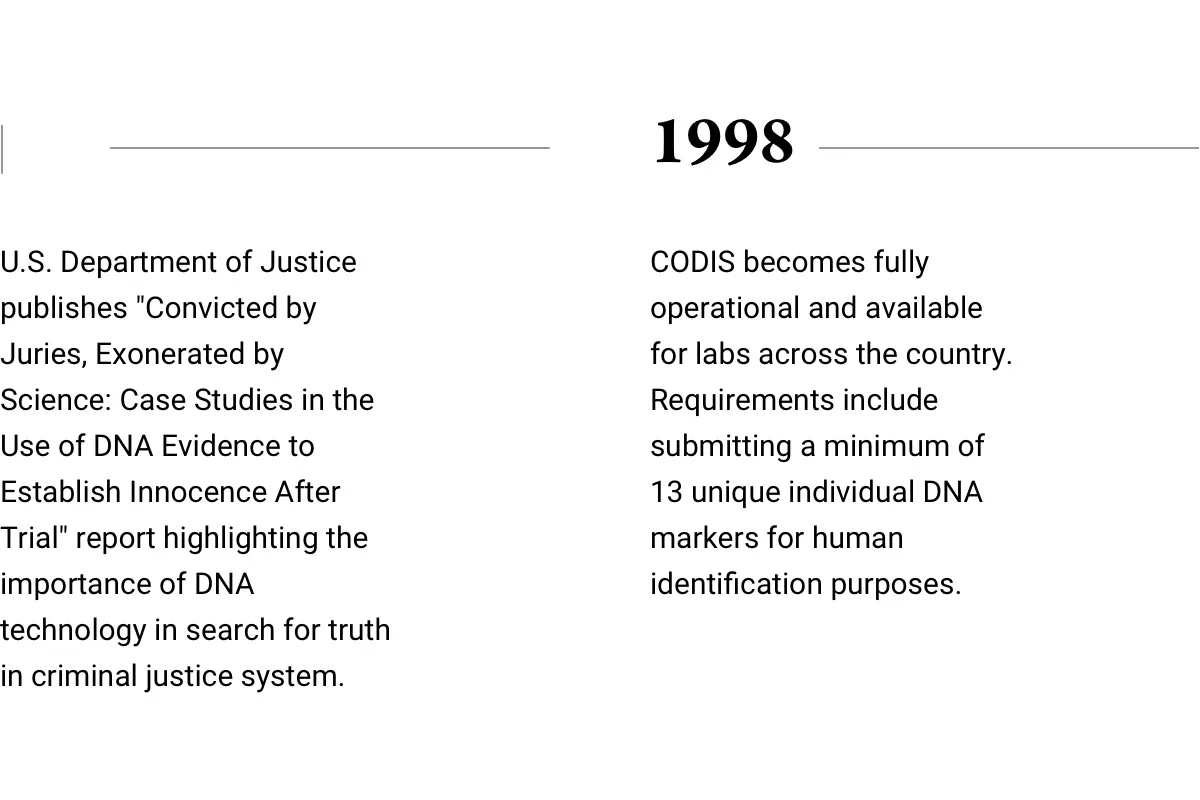

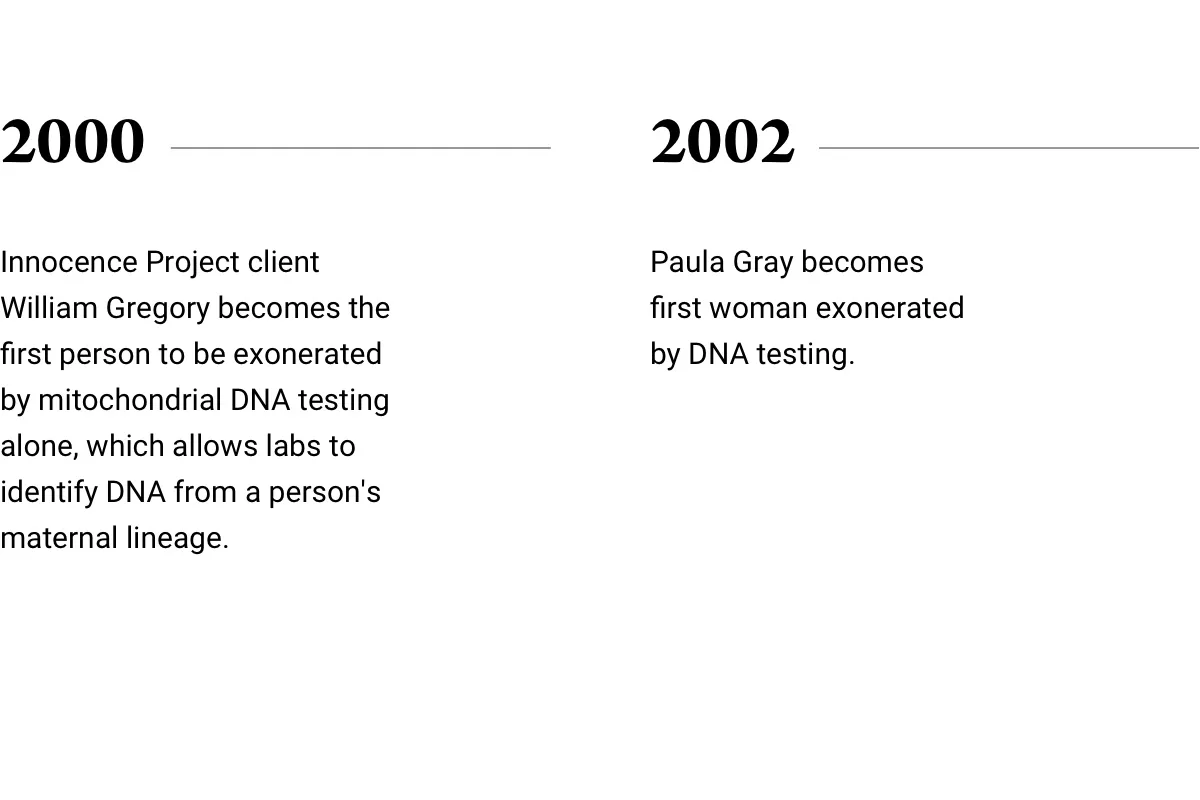

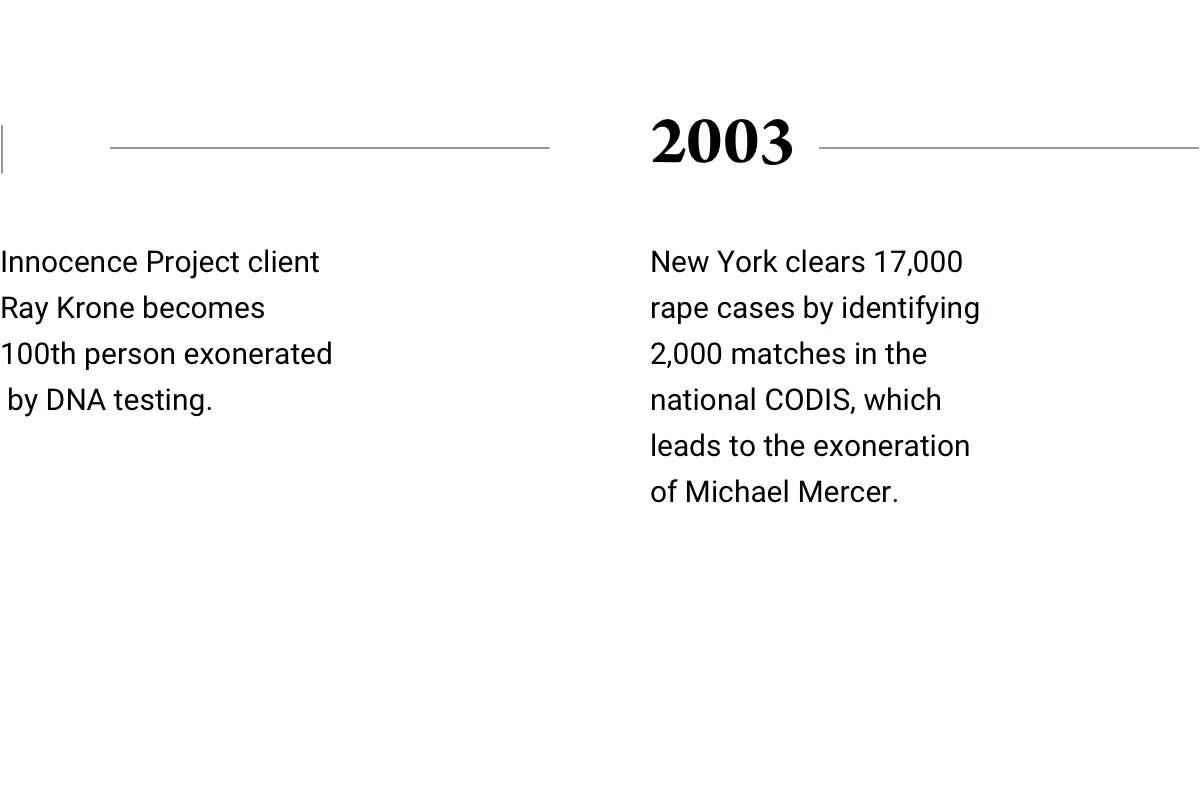

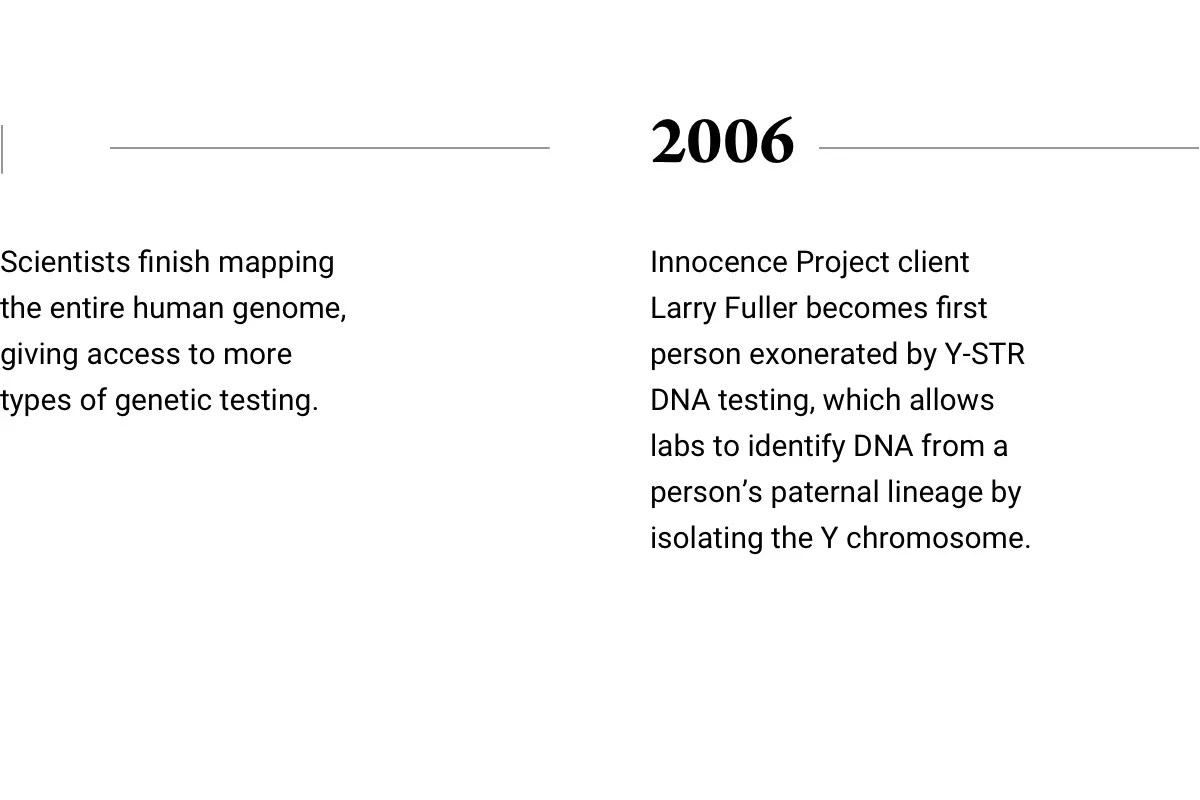

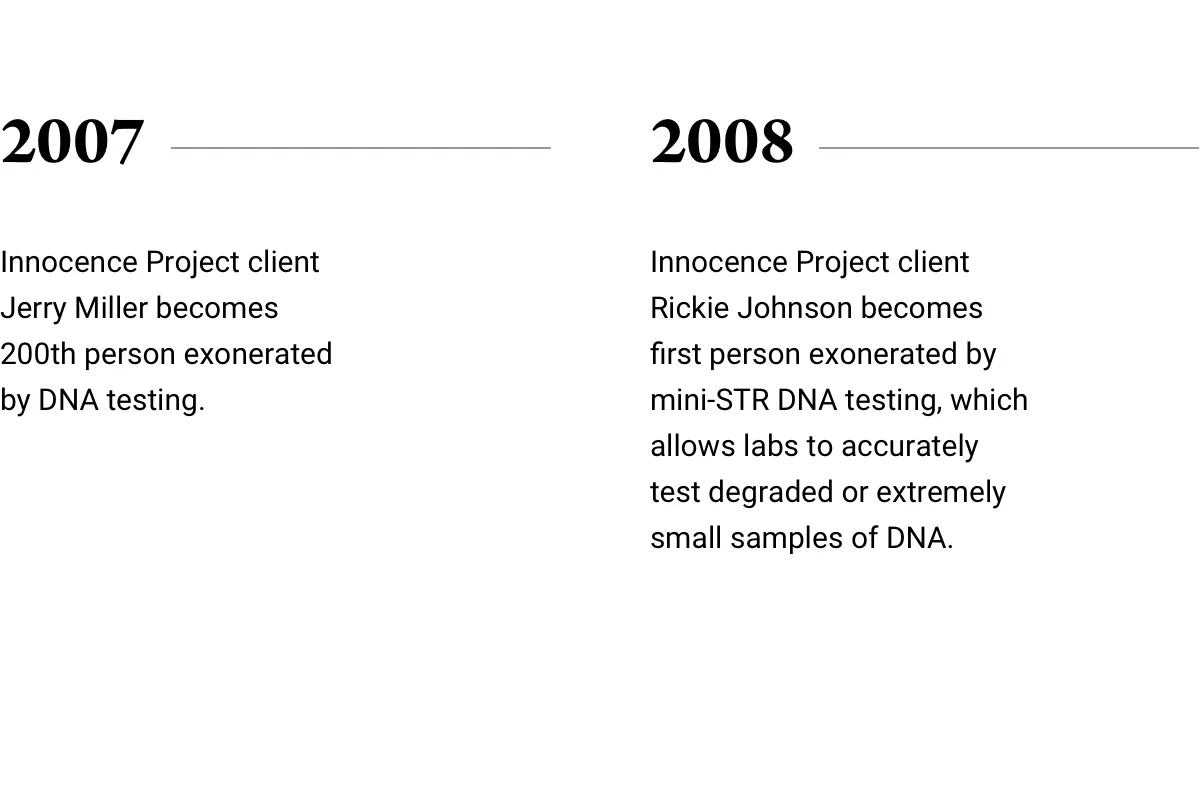

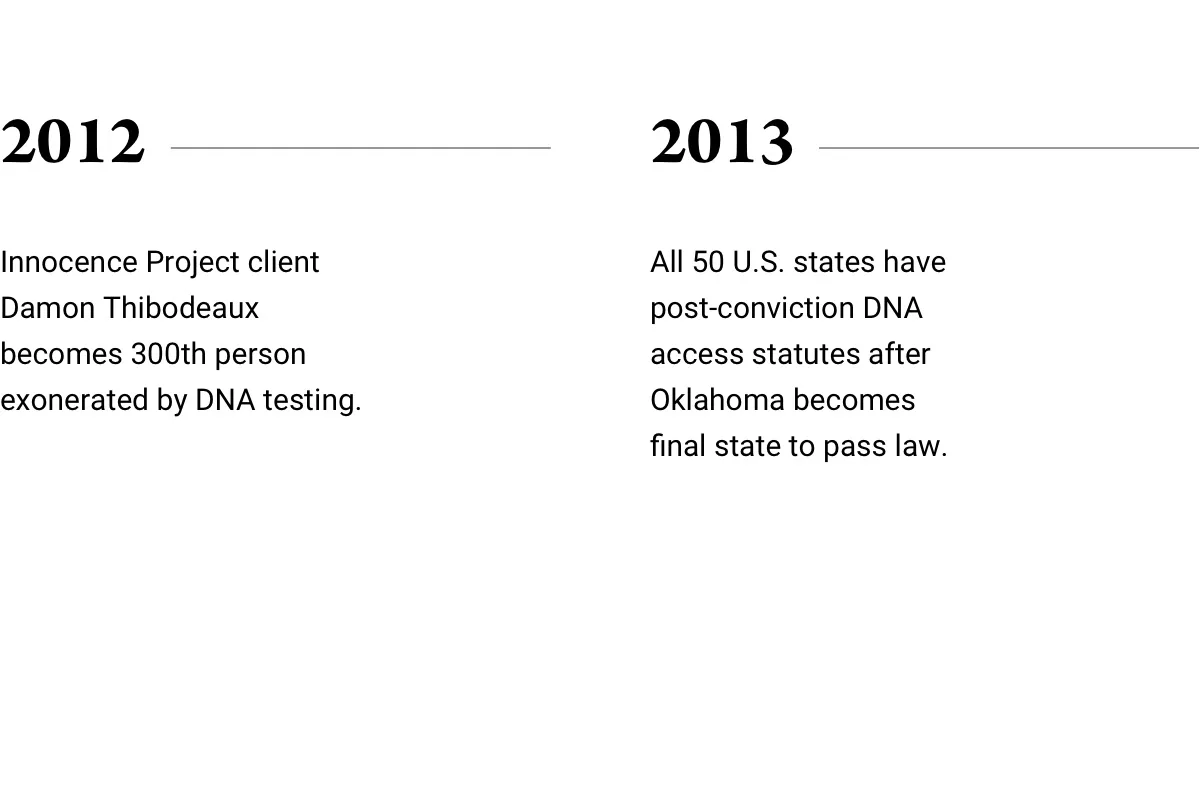

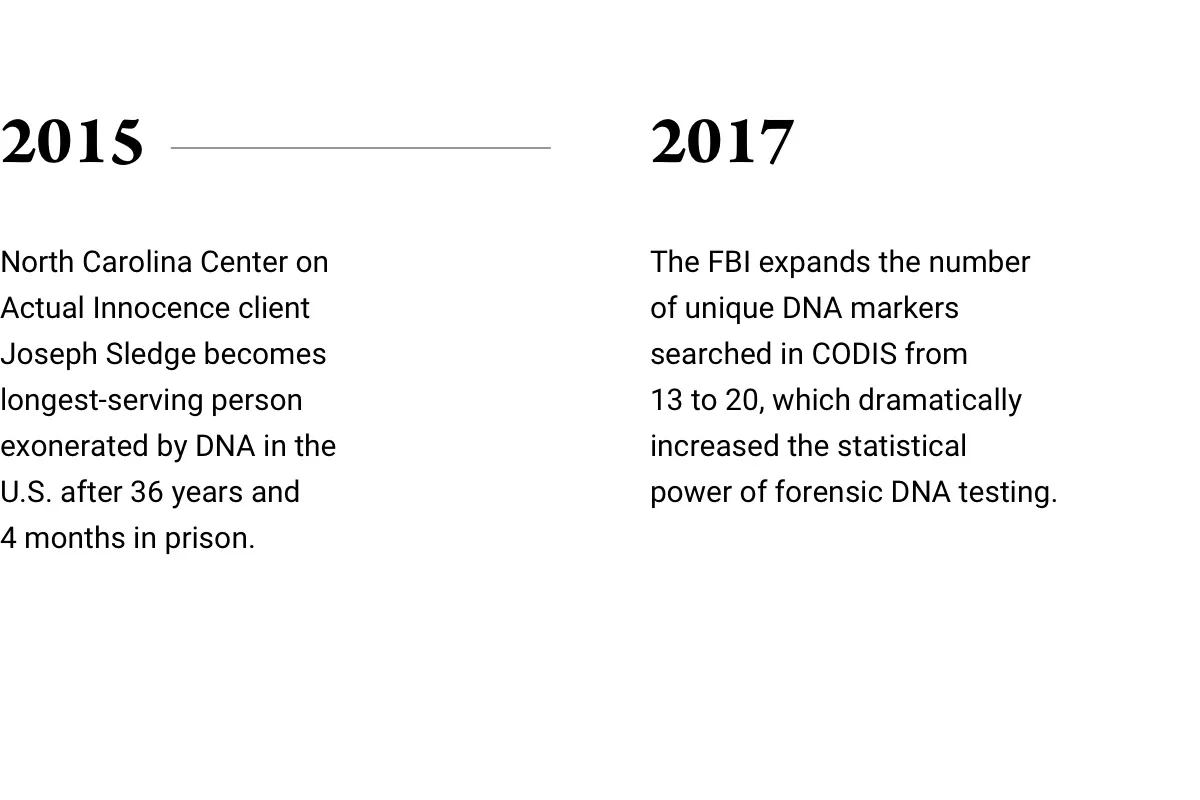

Below is a timeline of historic moments and stories to show the revolutionary impact of DNA on freeing innocent people and reforming the criminal justice system in the United States.

“We knew that this new DNA technology would not only prove people guilty, but also prove people innocent.”

“We knew that this new DNA technology would not only prove people guilty, but also prove people innocent.”

Barry Scheck Innocence Project Co-Founder and Co-Director

How Innocence Project Uses DNA

The Intake Process

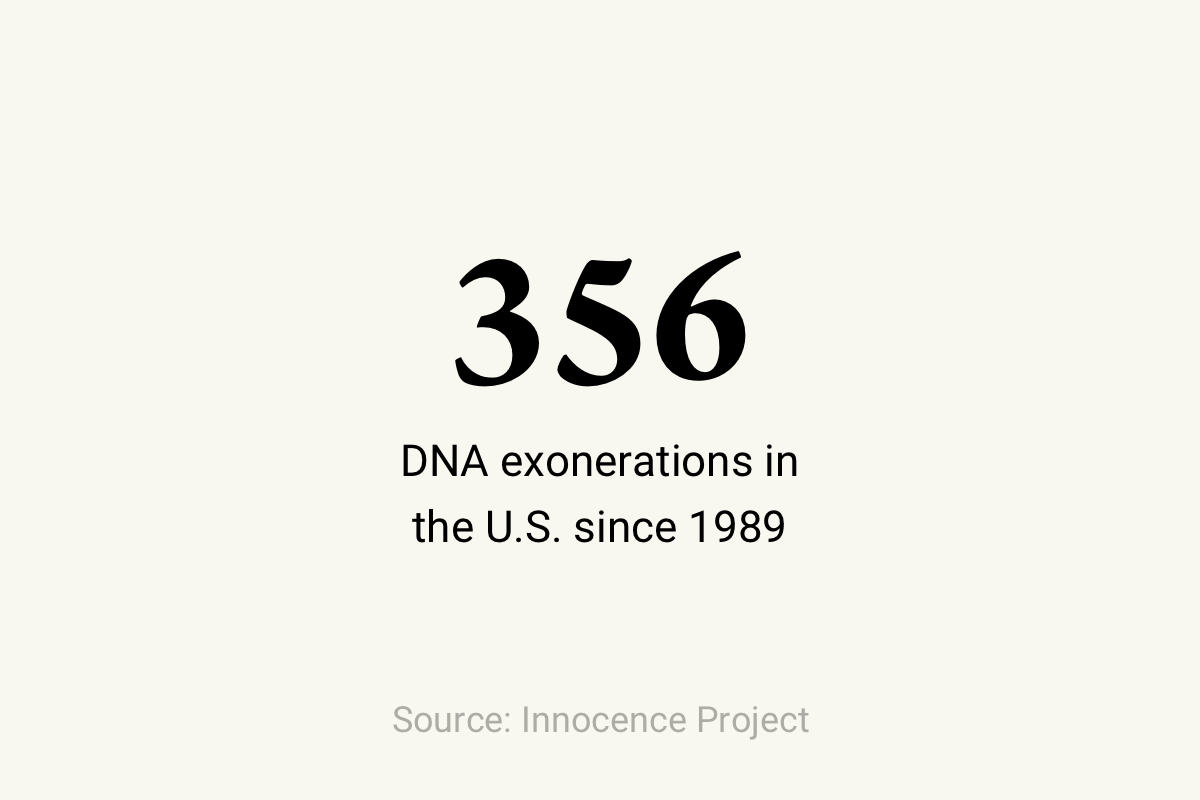

Since 1993, the Innocence Project has received over 50,000 letters from incarcerated individuals seeking help in proving their innocence.

The Innocence Project conducts an extensive evaluation of cases to determine 1) whether the identity of the perpetrator is at issue, 2) whether the perpetrator potentially left behind biological evidence, and 3) whether the biological evidence was collected and what new testing may be conducted on the evidence. The viability of the person’s innocence claim is also assessed.

Generally, we can prove the defendant’s innocence if the defendant is excluded from a probative item or multiple probative items left by the perpetrator. In some cases, DNA testing may also develop a profile that matches to an alternate suspect or to someone in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), the national DNA database of offenders, missing persons and forensic materials collected from crime scenes.

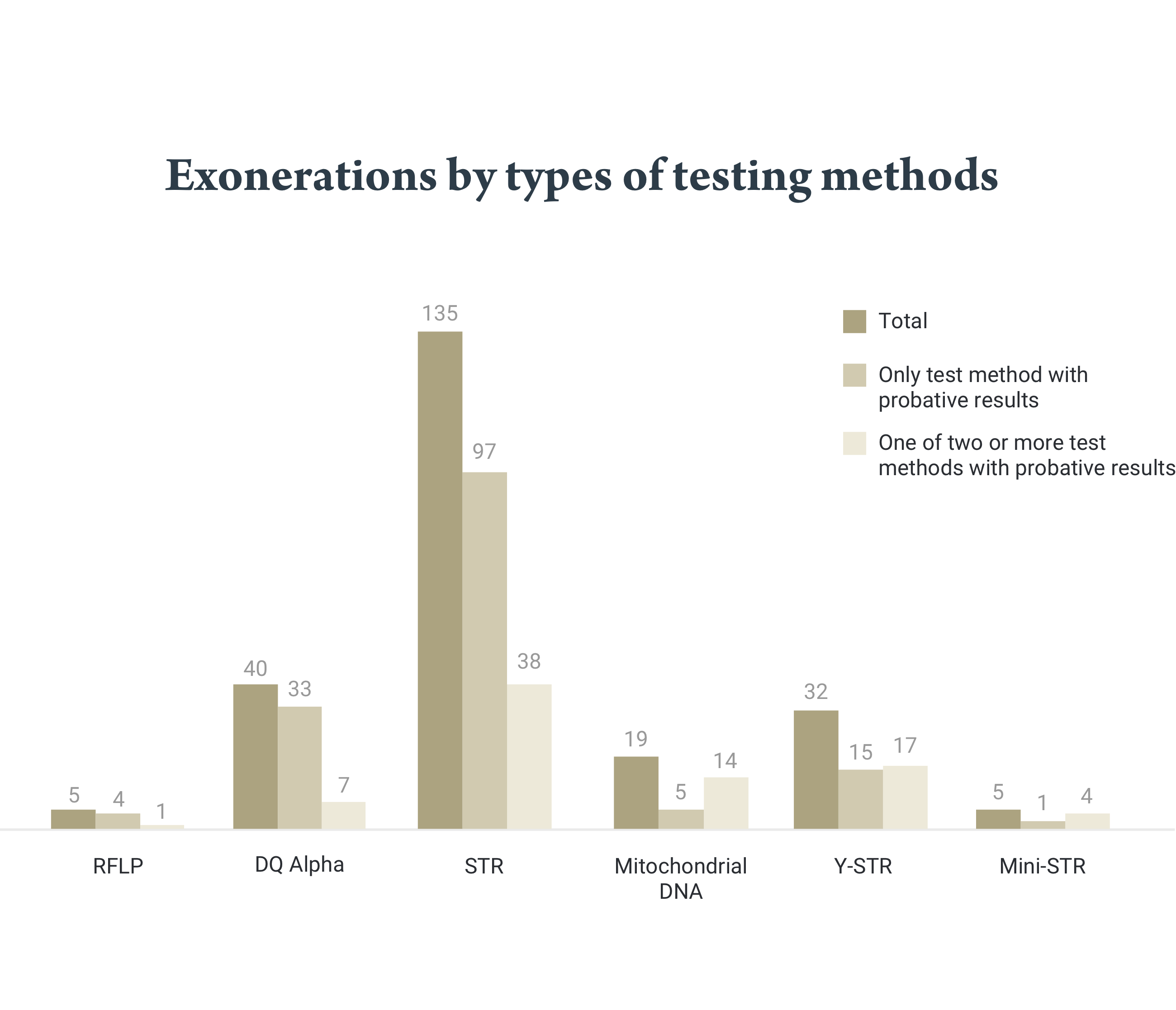

Below is a chart on the types of DNA testing methods that were used in the first 194 DNA exoneration cases:

Hampikian, West, Akselrod, “The Genetics of Innocence: Analysis of 194 U.S. DNA Exonerations”, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2011. Vol. 12:97-120.

Chart Key

RFLP: Restriction fragment length polymorphisms. First type of DNA testing used in the criminal justice system. Required a large amount of DNA to be present for testing.

DQ Alpha: Second iteration of DNA testing and incorporated a new step in testing that allowed smaller amount of DNA to be subject to testing, however, was not very discriminatory.

STR: Analysis of STR regions on DNA. This is the gold standard of DNA testing and the method used by all forensic DNA laboratories. This type of testing is highly sensitive and discriminatory.

Mitochondrial DNA: Analysis of DNA from a person’s maternal lineage. Tests crime scene evidence for mitochondrial DNA that is inherited maternally. Most helpful in testing hair and bone samples.

Y-STR: Analysis of DNA from a person’s paternal lineage by isolating the Y chromosome. Test crime scene evidence for male DNA; most helpful in sexual assault cases.

Mini-STR: Analysis of DNA from degraded or extremely small samples. Similar to STR testing but used for evidence that may be degraded.

“What you want to do in the criminal justice system is ultimately develop the most scientifically rigorous, reliable methods so we can all get to the truth and victims can be more satisfied, defendants can be more satisfied and the public can rest assured that we reached the right result.”

“What you want to do in the criminal justice system is ultimately develop the most scientifically rigorous, reliable methods so we can all get to the truth and victims can be more satisfied, defendants can be more satisfied and the public can rest assured that we reached the right result.”

Peter Neufeld Innocence Project Co-Founder and Co-Director

Litigation Process

Once cases are selected based on the likelihood that DNA testing can be used to prove innocence, there are two steps to the litigation process: 1) accessing the evidence that may be suitable for DNA testing through court proceedings; and, 2) litigating on behalf of the client and arguing for relief based on exculpatory evidence.

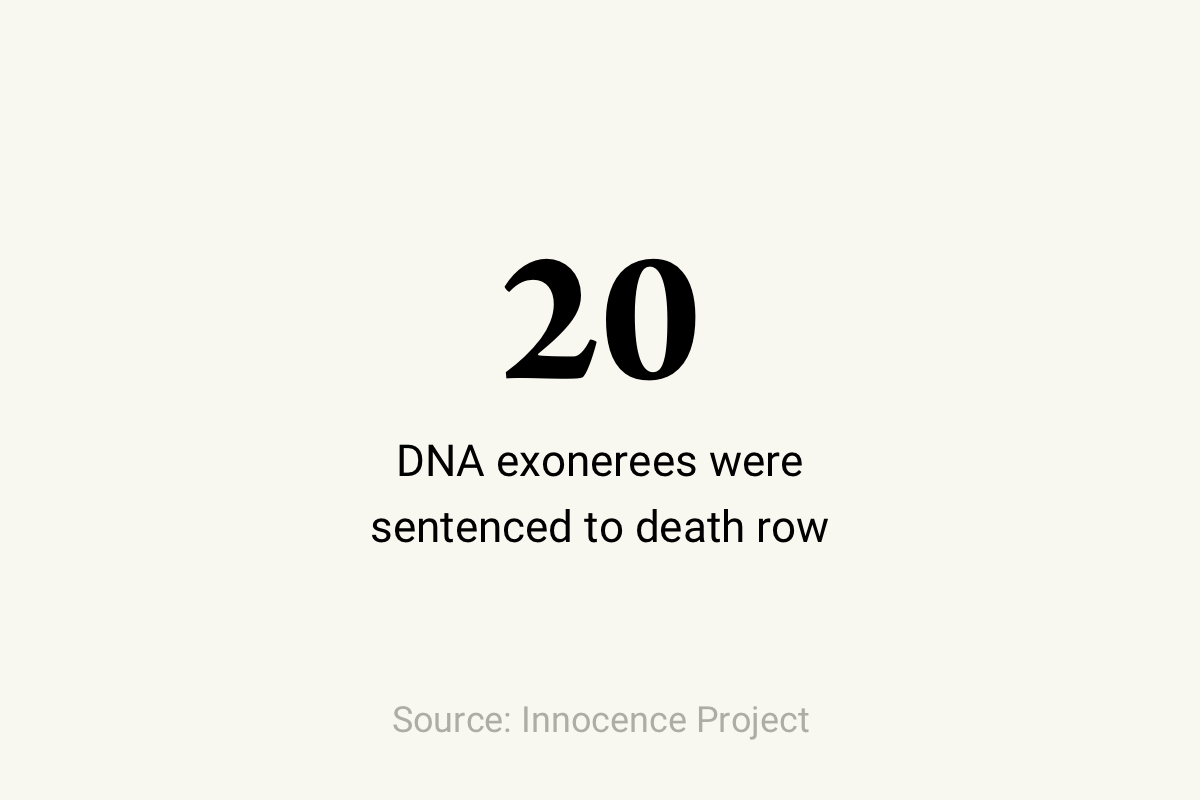

Although a seemingly clear process, these two stages can take decades before an exoneration occurs.

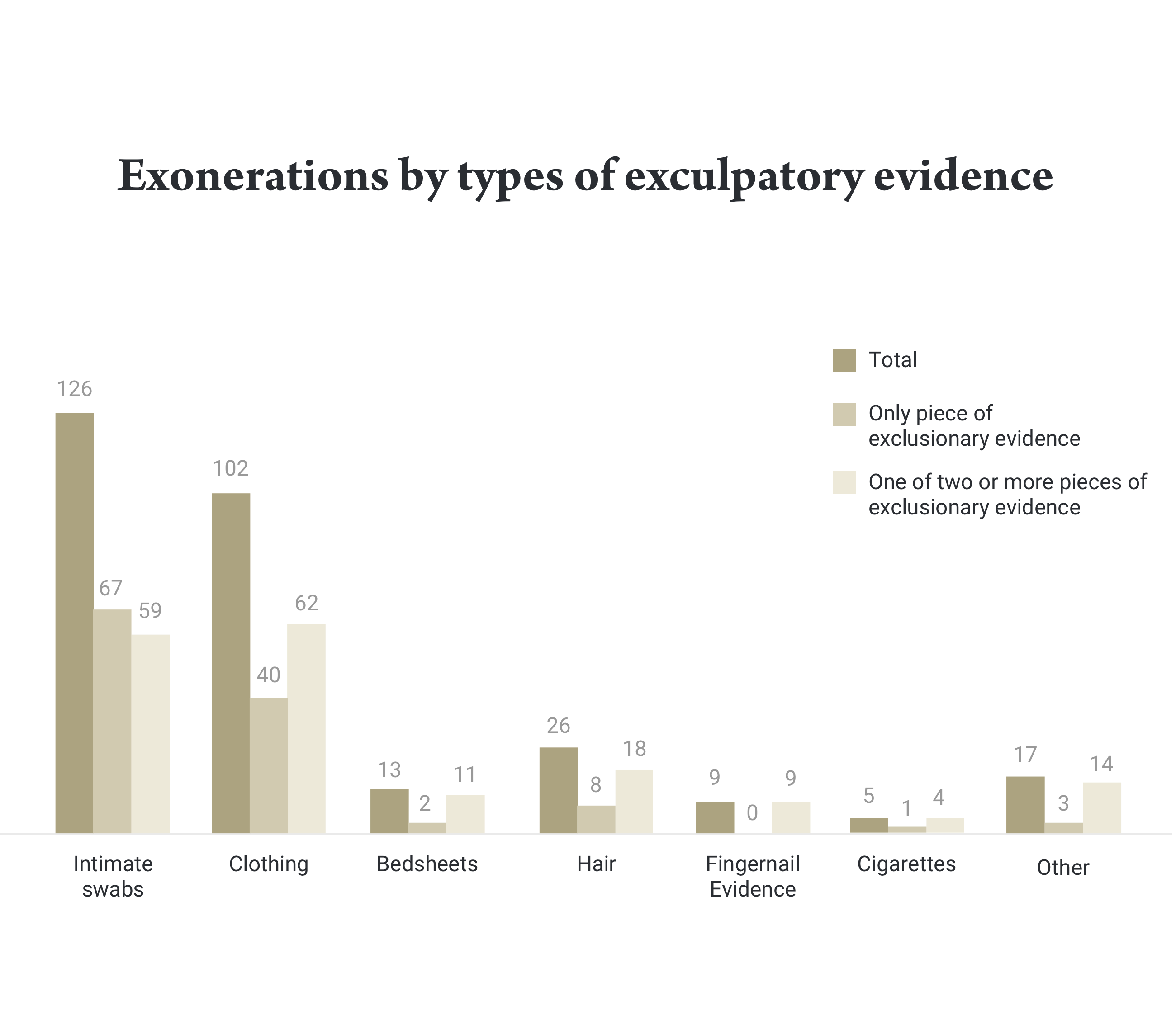

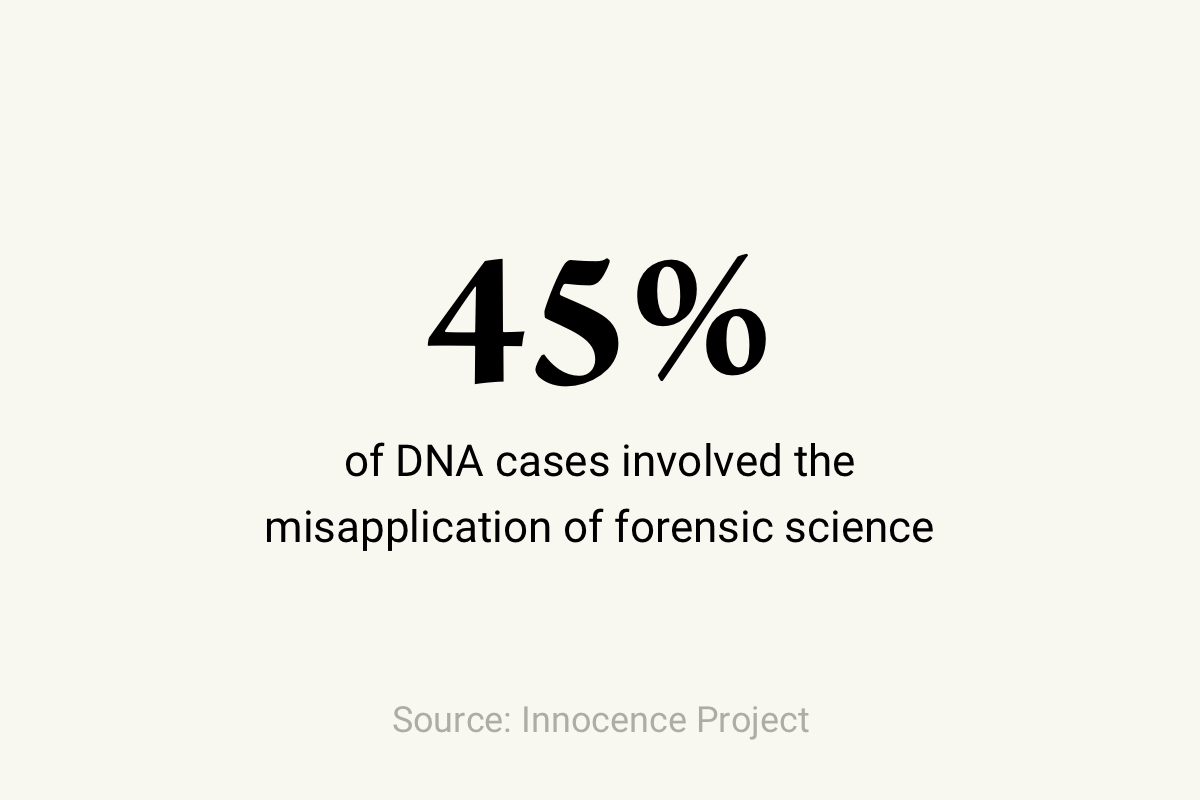

Of the first 194 DNA exonerations, the types of exculpatory evidence that helped prove defendants innocent can be seen in the graph below:

Hampikian,West, Akselrod,”The Genetics of Innocence: Analysis of 194 U.S. DNA Exonerations“, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2011. Vol. 12:97-120.

“Gary Dotson wants to remove the stigma of being a convicted felon ... This will be independent, scientific evidence that proves conclusively that he had nothing to do with Cathleen Crowell [Webb].”

“Gary Dotson wants to remove the stigma of being a convicted felon ... This will be independent, scientific evidence that proves conclusively that he had nothing to do with Cathleen Crowell [Webb].”

Thomas M. Breen Lawyer to Mr. Gary Dotson, The New York Times

Gary Dotson: First Person Exonerated by DNA

10 Years in Prison

In July 1979, Gary Dotson was convicted of aggravated kidnapping and rape of 16-year-old Cathleen Crowell Webb in a Chicago suburb and sentenced to 25-50 years in prison.

The teen identified Dotson from a police mugshot book and police lineup.

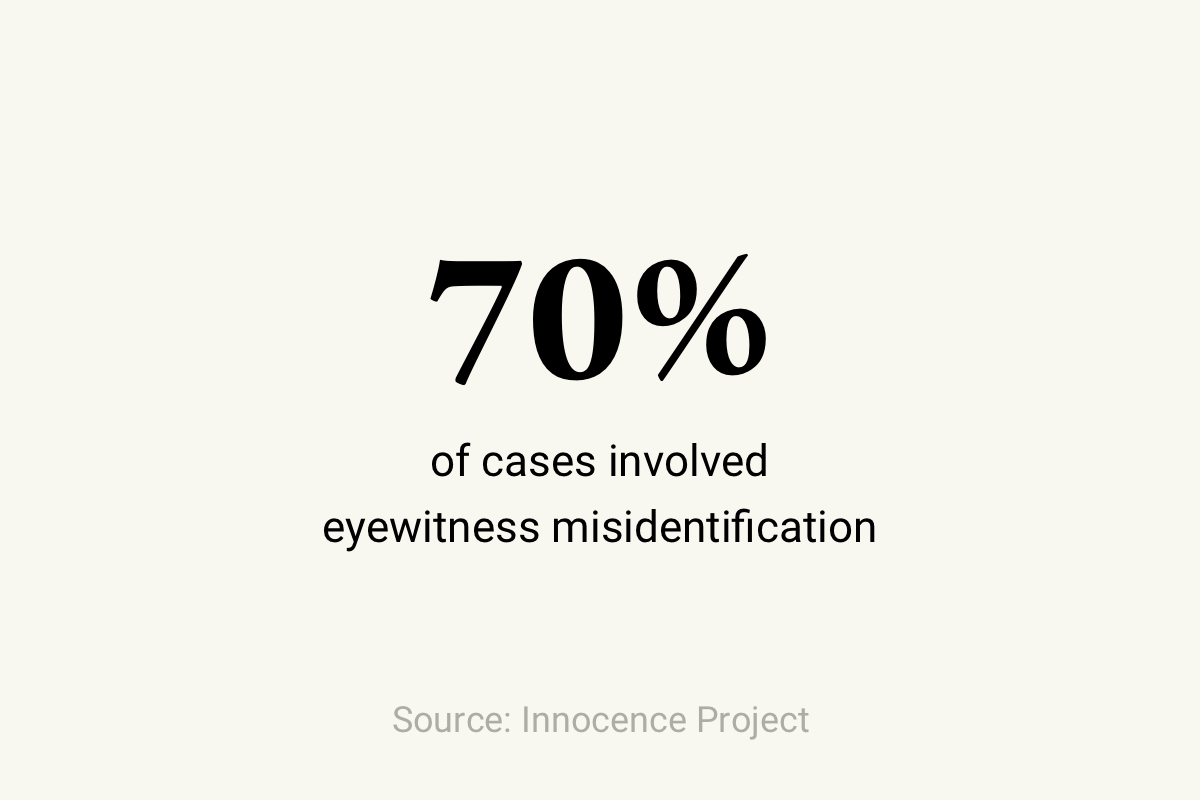

Later at trial, the prosecution included the composite sketch of the assailant that was prepared by the police with Webb’s assistance. Eyewitness misidentification coupled with flawed serology and improper hair analysis during trial helped secure Dotson’s conviction.

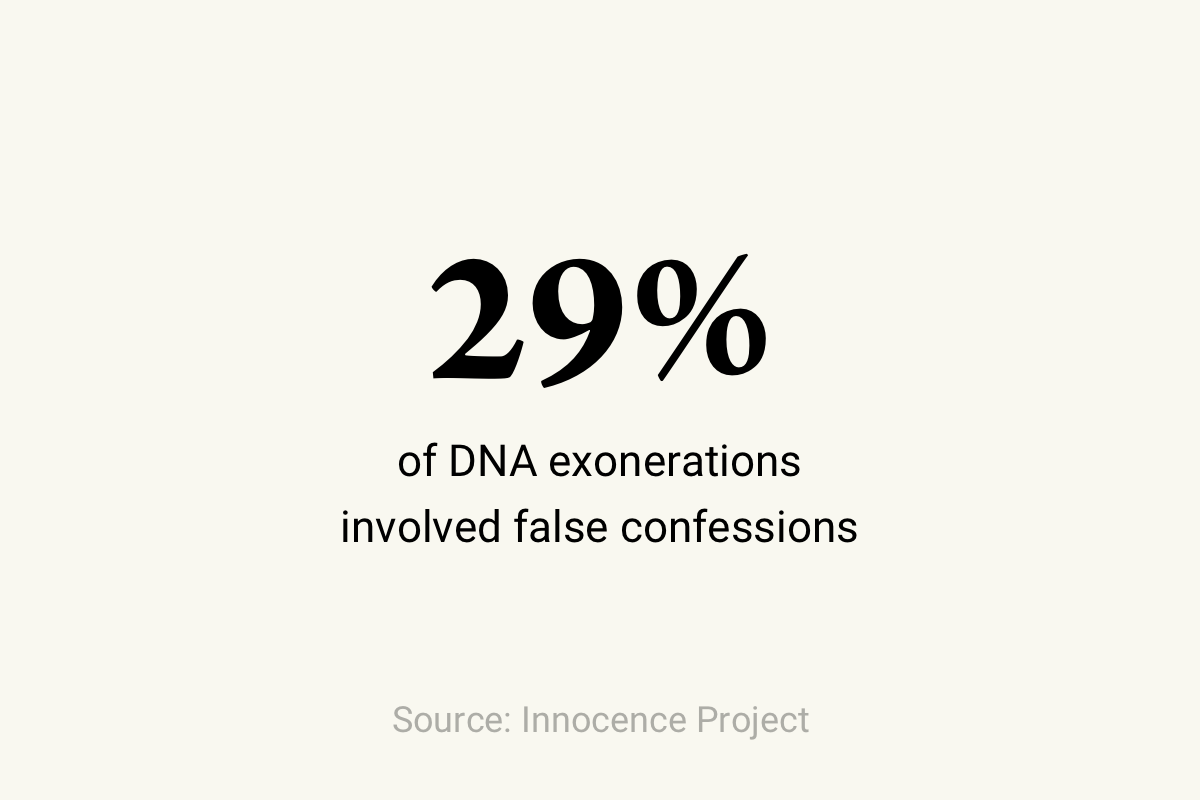

In March 1985, Webb recanted her testimony, admitting that she fabricated the rape to hide a consensual sexual encounter with her then-boyfriend. Dotson contended that the victim’s recantation of testimony constituted grounds to vacate the original sentence but was denied a new trial.

Dotson’s attorney Warren Lupel petitioned Governor James Thompson for clemency. Instead of taking a recommendation from the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, Thompson decided to preside over the hearing. The case was already highly publicized and this intensified when the review board televised the graphic proceedings. The governor refused to believe Webb’s recantation, and Dotson was denied a pardon, losing another chance at justice.

After several years of having his parole denied, Dotson’s new attorney Thomas M. Bree had DNA tests conducted, not available at the time of trial, which matched Webb’s boyfriend at the time of the crime, and not Dotson.

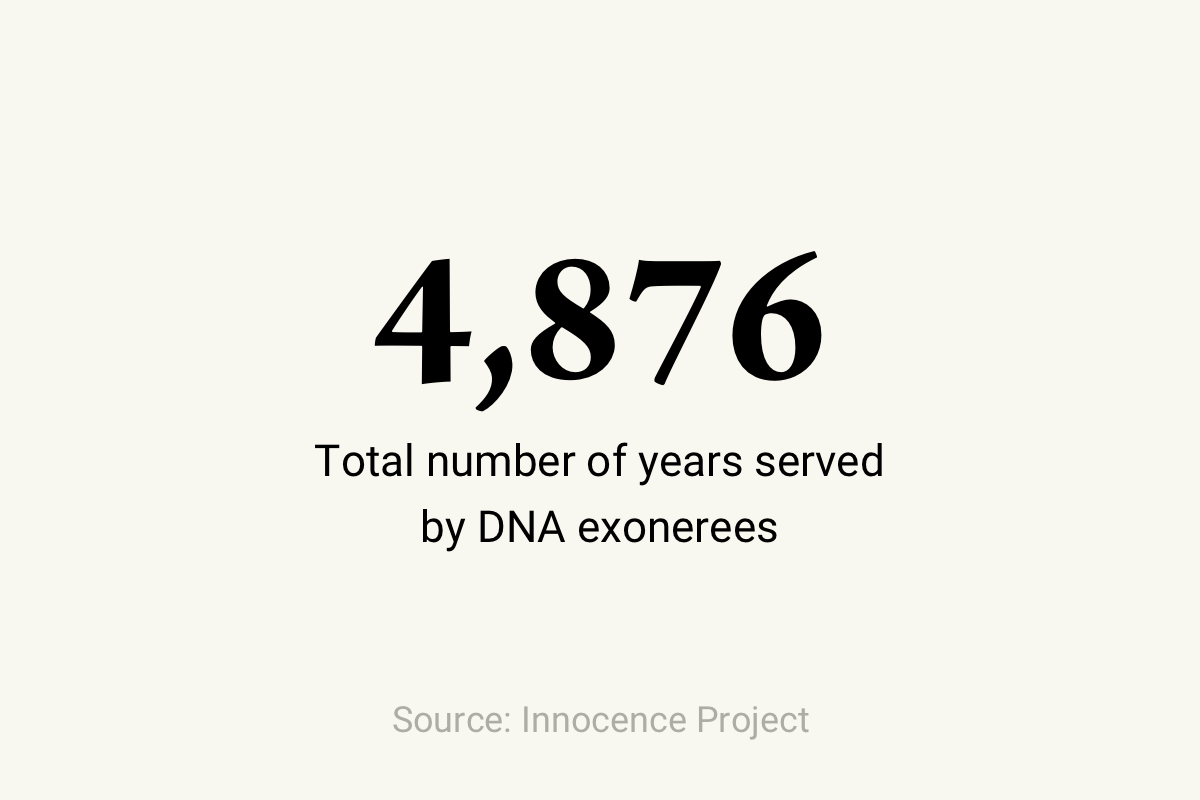

Finally, the chief judge of the Cook County Criminal Court ruled that Dotson was entitled to a new trial. The state’s attorney office, however, decided not to prosecute based on the DNA test results. Dotson’s conviction was finally overturned on August 14, 1989, after he had served 10 years in prison.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.