Albert Woodfox: A ‘Country Boy’ Turned Black Panther Reflects on Life After 45 Years of Solitary Confinement

Despite the grave injustice of his wrongful incarceration and the horrors of sustained solitary confinement, Mr. Woodfox emerged an activist whose spirit remains unbroken.

Special Feature 02.19.21 By Alicia Maule

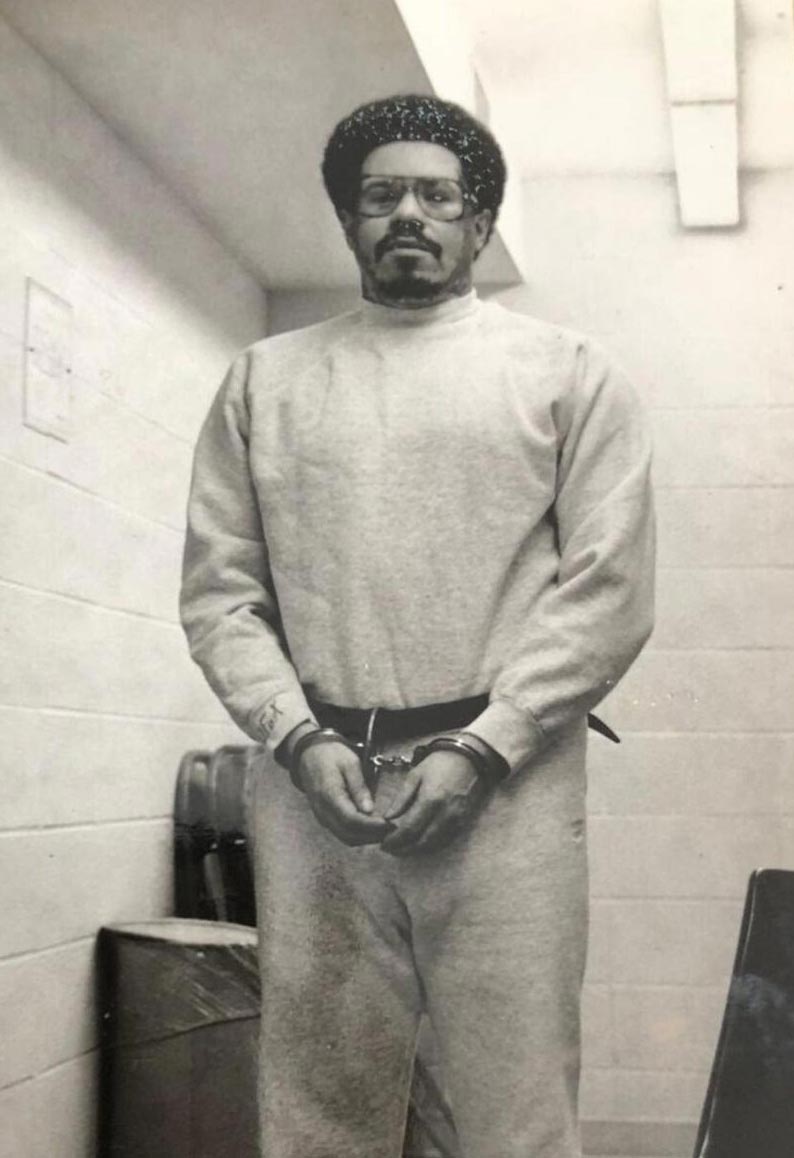

Albert Woodfox detained in Angola prison. (Image: Courtesy of Albert Woodfox)

Update (8/4/22): On August 4, 2022, Albert Woodfox, with an unbreakable spirit, passed away. On the day of his passing, his attorney George Kendall sadly remarked, “There will be a huge hole in the sky tonight.”

On Feb. 19, 2016, Albert Woodfox was freed after 44 years and 10 months of incarceration — almost all of which he spent in solitary confinement. At the age of 69, after having his conviction overturned three times, and enduring a trial and retrial, he entered an Alford plea. With this deal — in exchange for his immediate release — Mr. Woodfox maintained that, while the evidence against him might be sufficient to convict again, he was innocent.*

Despite the grave injustice of his wrongful conviction and the horrors of sustained solitary confinement, Mr. Woodfox emerged an activist whose spirit remained unbroken. He is a living wellspring of history, a former Black Panther whose Black radical ideology is rooted in his belief in humanity and profound love for his mother, Ruby Edwards.

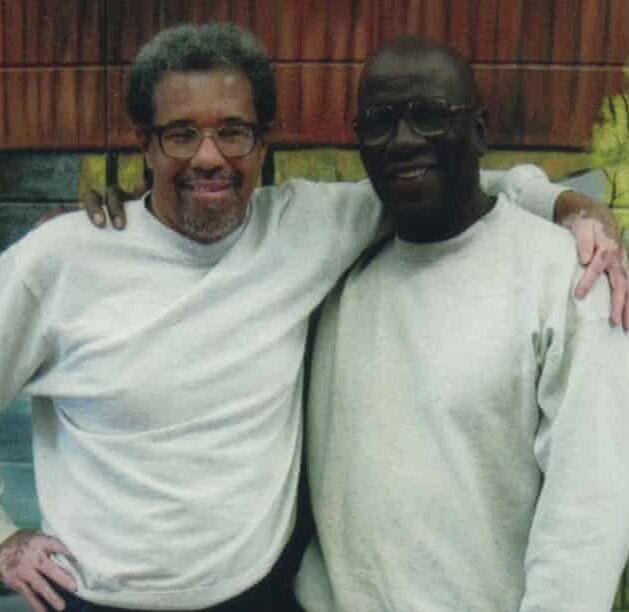

He tells his story in detail in Solitary, a 2019 non-fiction National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist. In 1972, a white correctional officer at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (known as Angola prison) was killed. Two prisoners and Black Panthers — Mr. Woodfox and Herman Wallace — were immediately targeted as suspects, despite a lack of evidence, and convicted. Together with Robert King, a fellow Black Panther convicted of a separate murder in prison in 1973, the men became known as the Angola Three. All three maintained their innocence for decades.

Mr. Woodfox is widely reported to have served the longest time in solitary confinement of any person in the U.S. His story has inspired both debate around the cruelty of solitary confinement and meaningful reform.

Throughout his wrongful imprisonment, Mr. Woodfox supported those incarcerated alongside him at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola prison — a moniker taken from the former plantation upon which the prison was built. He helped educate other incarcerated people and organized hunger strikes for humane treatment. His goal was and continues to be to leave the world a better place for his grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and all the generations after him, just as he believes his African ancestors did for him.

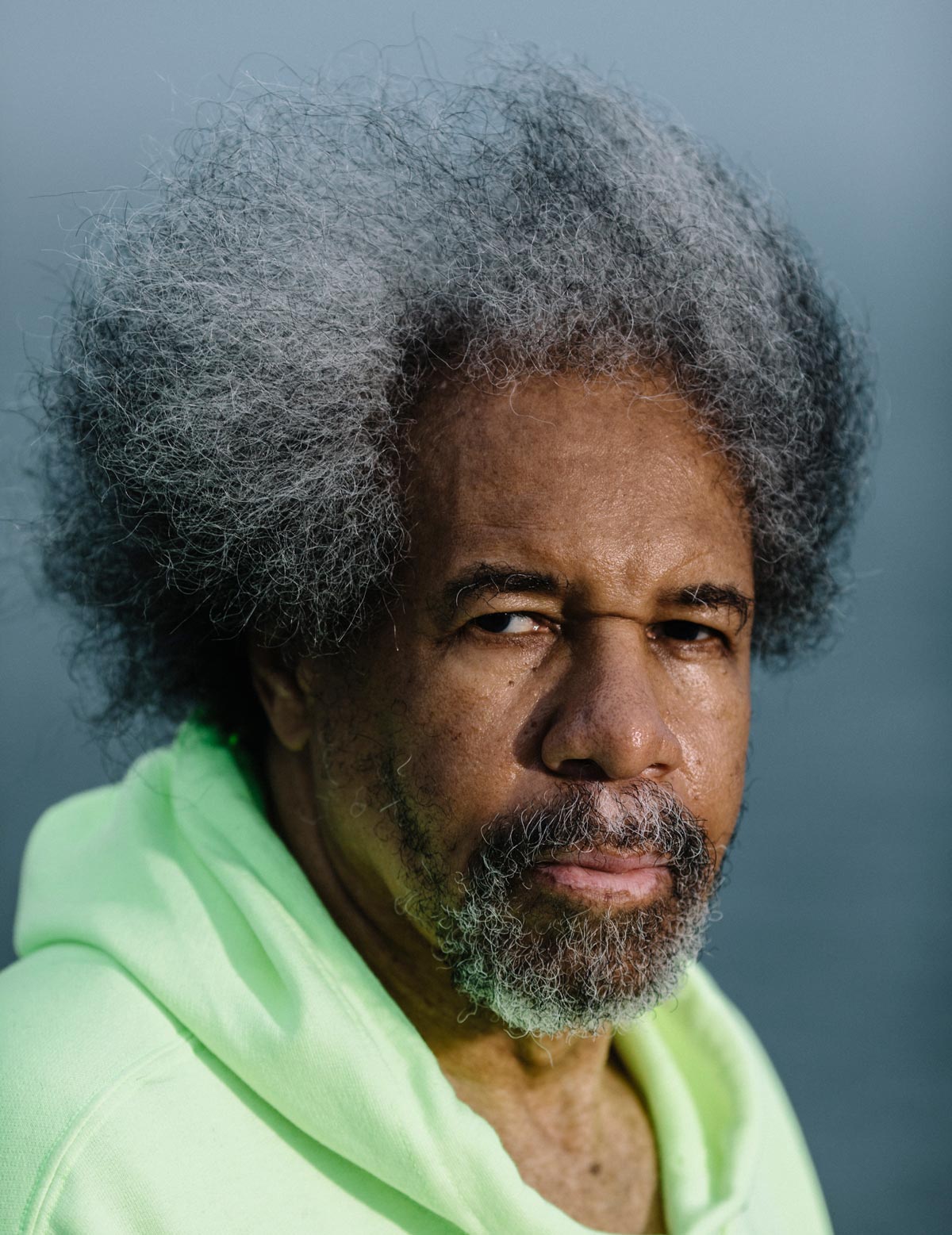

Mr. Woodfox did not allow solitary confinement to defeat him. Through the injustice he survived, Mr. Woodfox said he liberated himself intellectually and spiritually despite his physical confinement — which is why he considers today, the fifth anniversary of his release, the anniversary of his “physical freedom.” It also happens to be his 74th birthday.

To mark the occasion, we spoke to him about his long journey to justice. And to adequately capture the full weight of Mr. Woodfox’s words and his profound thoughts, expressed in his New Orleans Yat accent, video clips from our conversation, conducted over Zoom, are included here to bring his full story to life.

*Mr. Woodfox was represented pro bono by Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLP. His lead counsel included Carine M. Williams, who is today the Chief Program Strategy Officer of the Innocence Project.

Albert Woodfox interviewed by Innocence Project Digital Engagement Director Alicia Maule on Zoom in February 2021. (Image: Alicia Maule/Innocence Project)

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The fifth year anniversary of your release and your 74th birthday are coming up. What have you learned since you’ve been out?

Nothing has changed other than technology — I learned that after three weeks of being back in society. While in prison my only window to society was a TV or magazine — things we had earned over the years and decades through struggle, hunger strikes, and various other forms of struggle. I saw a lot of change. Once I was in society, the instinct and intuition kicked in and I’m like … only thing that has changed is technology. How can I come out in society, and realize that the same forces that oppress my ancestors are still here active as ever?

I’m with you! What does your Afro mean to you?

It’s a symbol. It’s a statement: It means here I am … My African pride. The old saying “fried, dyed, and laid to the side” doesn’t apply to me. It never has, it never will.

What are you most proud* of?

Robert King and I, wherever we went to speak, always asked the inviting body to let us meet with some of the young leaders of the Black lives movement. This is when Black Lives Matter wasn’t fashionable, and it was one of the most hated groups in America. Robert and I both saw the potential of the Black Lives Matter movement and their resemblance to the Black Panther Party. I think it’s the most promising movement in this country.

*Albert Woodfox has also said that he is most proud of helping Charles “Goldy” learn how to read in Angola.

Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox in Angola prison. (Image: Courtesy of Albert Woodfox)

How do you see the impact of the legacy of the Black Panthers? Where do you see it today?

I was watching a program on the History Channel and it was about gangs. Imagine my surprise when the historian referred to the Black Panther Party as a “gang,” rather than a political organization. And that was because white America, particularly the FBI, set the narrative and told the history of the Black Panther Party. We are at a stage now where you have a lot of Panther alumni groups starting to go out to the community. We’re telling our story, we’re telling the accomplishments and the contributions that the Panthers made. Most of all, the courage that it took for these men and women in those times to do what they did.

Can you say why the Black Lives Matter movement is promising to you?

Its concern with humanity, building the value of humanity, building a better society. Taking on institutional and individual racism and white supremacy. One of the guys I truly admire and I even would see as my hero is Colin Kaepernick. I don’t think America really understood the sacrifice that this man made. I think he set the mold for what being an African American male really is. There are many great athletes and entertainers that I admire, and there are some I’m disappointed in. Especially those who I consider to be betraying our African people in our history when they embrace this white supremacist President Donald Trump. I still have problems understanding how they could forget the history from 1619, when the first slaves were brought to this country, until now. The murder, the rape, the brutality, the destruction of culture, and language, to the crushing of our dignity, pride, self respect.

“It never ever came close to breaking my spirit. And that's what solitary confinement is designed for.”

“It never ever came close to breaking my spirit. And that's what solitary confinement is designed for.”

Albert Woodfox

How far back can you trace your family history? And what are some of your favorite childhood memories?

Leslie George (his partner and co-author of Solitary) and I traced the name Woodfox and come to find out it’s owed to Native American names. Neither one wanted to change their last name, so they combined Wood and Fox. Many years ago, a friend of mine traced Woodfox … we go back to the 1700s in Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, Florida. I knew that the word Fox was a Native American name, but I never knew that it was a combination of two names.

My grandparents on my stepdad’s side come from a small town in La Grange, North Carolina.

But we basically lived in the Sixth and Seventh Ward over the years. Rampart Street. Some of my favorite things during my childhood was playing ball on neutral ground.

And my aunt’s cooking, you know? The three of them would get in there — my aunt Florence, my mom, and my aunt Gussie. I would smell the odors from cooking when we were in North Carolina or in New Orleans. I’m used to Black women getting in that kitchen, and all the old recipes start coming out and the whole house is filled with the aroma. And then you can hear the kids and see your kid riding up and down the block, playing in the street.

Do you like gumbo?

[Laughs] Oh I love gumbo … I love Soul Food. But I can cook — gumbo, fried chicken you know all the basic staples. Mom and my aunts made sure that all of us could cook and clean the house. My favorite meal though is creamed corn, rice and smoked sausage. When I got out of prison I went to my daughter’s house for the first time because she was an infant when I left society, and she prepared some creamed corn, rice, and smoked sausage, which was absolutely delightful.

Tell me more about your daughter.

Her name is Brenda. I have three grandkids, and I have four great-grandkids. They are the delight of my life. They’re also one of the motivating factors of why I’m still active in social struggle. I would like to leave a better world for them. And for me, I would hate to think that 30 years from now they’re fighting the same battles.

You mentioned your mom, tell me what you loved about her.

My mom was functionally illiterate, but she was probably one of the smartest women. Those qualities that I had, she had instilled in me by example: internal strength, fortitude, determination, strong sense of loyalty.

I never saw all that racist society had done to her. I never saw them break her. I never saw a moment when she had just resigned herself to the status quo, she always fought. During 44 years and 10 months in a prison cell, and being actively involved, organizing, and resisting, I had a lot thrown at me. And you know, a lot of pain and suffering, but I can honestly say I’ve never ever thought of giving up. It never ever came close to breaking my spirit. And that’s what solitary confinement is designed for … to break people.

Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace in Angola prison. (Image: Courtesy of Albert Woodfox)

What impact has your case had on policy in Louisiana?

Robert and Herman and I filed a civil suit about long-term confinement. And since that time, solitary has become a discussion nationwide — now, worldwide. I like to think that the work Robert, Herman and I started that conversation or contributed to that conversation. There hasn’t been much change, but there have been some minor movements. In Angola prison, there have been some changes. It’s not as easy for security people to put you in solitary confinement as it was one time, but it still exists. And as long as it exists, it is a threat to humanity. It is a threat to an individual’s dignity and pride, self respect, because that’s what solitary is.

What are a few of your favorite songs?

I’m an old R&B man. Some of my favorite singers are Aretha Franklin — of course, the Queen of Soul — Ray Charles, Gladys Knight and the Pips. I love hip hop. I understand the movement.

Hip hop or rap is history for African Americans. We had members in tribes whose responsibility to the village was to record their history and to remember their history. It’s a way of expressing what we are going through right now. What’s being done to us and how are we going to fight it. It’s a wonderful form … And I love Ebonics. You know, I think Ebonics is probably one of the most beautiful forms of communication that exists.

So is your second book going to be about your love for Ebonics?

It’s strange you say that because I just bought a typewriter. I haven’t set a specific date, but one day I’ll just sit and start typing. Primarily the book will be on what life has been like with my observation and experiences since I’ve been out.

“These are the principles I'm going to live by, these are the things that I'm willing to die for if necessary. And I think, so far, when I look in the mirror, I'm proud of what I look back at.”

“These are the principles I'm going to live by, these are the things that I'm willing to die for if necessary. And I think, so far, when I look in the mirror, I'm proud of what I look back at.”

Albert Woodfox

How do we fight racial injustice today?

I think we’re doing a great job refusing to accept it now by building a level of consciousness. Education is probably the greatest tool, in whatever form it is. It’s the greatest weapon you can use in social struggle to bring about change.

Individual acts don’t make change, mass movements cause change. Individual acts may create a momentary moment of awareness. I used to have a saying that “individual acts create chaos, mass movements bring about change”.

So who’s gonna play Mr. Woodfox in the Hollywood feature?

You’re not going to believe this. We have a deal with Mahershala Ali. I think he’s going to play my character.

He better start growing that Afro.

[Laughs] I’m sure special effects can help with that.

This journey has really, really tried me as a human being, and I’m happy to say that I’m very, very proud. My mom, when I was coming up, my mom used to tell me, “Boy when you look in the mirror, if you’re not proud of what’s looking back at you, then you not a man.” I didn’t understand that at that time. But, I always tell people, I grew into my mom’s wisdom.

That’s where [the poem] Echoes* come from. I think I was in my early 40s, when I really came to a point in my life where I said, “Okay, I’m ready. This is who I’m going to be until the ancestors call me. These are the principles I’m going to live by, these are the things that I’m willing to die for if necessary.” And I think, so far, when I look in the mirror, I’m proud of what I look back at.

*Albert Woodfox wrote the poem Echoes in 1995, a year after his mother died. Although his lawyers had arranged for him to attend the funeral and he was prepared to attend, at the last minute Angola prison officials denied him the opportunity to lay his mother to rest.

Echoes

Echoes of wisdom I often hear,

a mother’s strength softly in my ears.

Echoes of a womanhood shining so bright,

echoes of a mother within darkest night.

Echoes of wisdoms on my mother’s lips, too young,

to understand it was in a gentle kiss.

Echoes of love and echoes of fear

Arrogance of manhood wouldn’t let me hear,

Echoes of heartache I still hold close

As I mourn the loss of my one true hero.

Echoes from a mother’s womb,

heartbeats held so dear,

life begins with my first tears.

Echoes of footsteps taken in the past,

echoes of manhood standing in a looking glass.

Echoes of a motherhood gentle and near,

Echoes of a lost mother I always hear.

—Albert Woodfox, 1995

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.