Illinois Can Once Again Lead in Preventing Wrongful Convictions by Passing a Critical False Confession Bill

New proposed Illinois legislation would allow judges to rule on whether or not a confession is reliable – a key reform to prevent wrongful convictions.

Op-Ed 05.22.24 By Peter Neufeld and Steven Drizin

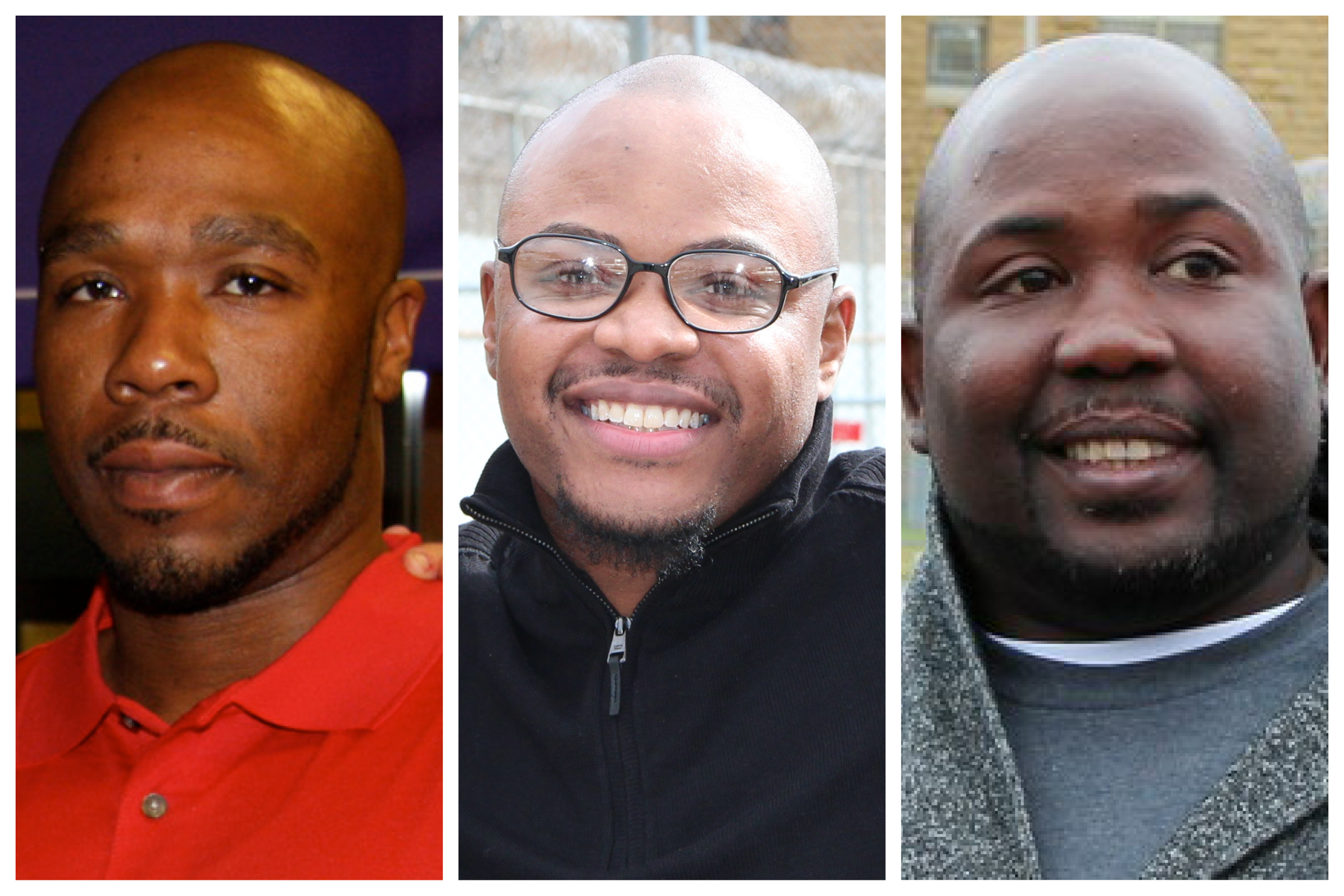

Robert Taylor, Jonathan Barr, James Harden, Robert Lee Veal, and Shainne Sharp, known as the Dixmoor Five, were all between the ages of 14-16 when they were wrongly accused of the 1991 rape and murder of a young woman in Cook County, Illinois.

Prosecutors argued that the confessions obtained from several of the young men were admissible because they were made voluntarily. The default test used by most courts to find voluntariness is whether the accused signed their Miranda warnings, which these teenagers signed. However, the mere acknowledgement that you are aware of your rights — for example, the right to remain silent — even assuming the full import of the waiver was understood doesn’t provide the court with any assurance that the confession is reliable.

Despite the fact that Illinois judges routinely rule on the reliability of other evidence, such as eyewitness identifications and forensic evidence, Illinois has not asked its judges to assess the reliability of the alleged confession. In the Dixmoor Five case, given that the DNA evidence, pre-trial, excluded each of them as the source of the semen on the victim’s body and their so-called confessions did not align with the other evidence, it is unlikely that a judge would have found the confessions reliable. Wrongly convicted, the Dixmoor Five spent a total of 95 years behind bars, losing years of their lives they can never get back, until they were exonerated. Meanwhile, the real perpetrator, subsequently matched to a DNA database search, remained free and, in fact, committed other sexual assaults.

Across the country, confessions that satisfy the “voluntariness” test can be admitted as evidence at trial, even if they are irrefutably false and unreliable, like those of the Dixmoor Five. In fact, attorneys for the Dixmoor Five moved to have their confessions thrown out, but were denied because the judge only considered voluntariness and not the confessions’ lack of reliability. Their case is just one of many demonstrating the need for a legal mechanism for judges to rule on whether a confession is reliable. Had this been in place and had their interrogations been recorded, it is likely the confessions would not have passed the test for admissibility — and the tragedy of their wrongful conviction might have been avoided.

Legislators have a chance right now to make such a provision possible — and they should take it.

Illinois is known as the wrongful conviction capital of the country. Illinois’ 540 exonerations tops the ranking of states, followed by Texas, with 474 exonerations. Illinois is also the false confession capital of the country. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 135 of the 445 exonerations nationwide that involved false confessions happened in Illinois — a full 30%. Almost all of these exonerees filed motions to suppress their confessions before their trials but because the judge merely tested voluntariness, all of these innocent people were convicted and spent decades in prison before they were cleared.

There are some telltale signs that a confession may be false. False confessions often fail to lead police to new evidence and may even contradict other witness testimony or physical evidence, as was the case with the Dixmoor Five. However, as it stands, judges are powerless and cannot choose whether to exclude or admit a confession from evidence based on its unreliability. This has to change.

Besides the obvious and terrible moral cost of these wrongful convictions, there is an economic cost to taxpayers not only in Illinois, but in every state across the country. Exonerees are often (and rightly) awarded millions of dollars in civil suits, and even the cost of opposing these lawsuits can run up to $5 million per case.

Representative Justin Slaughter, chairman of the Illinois House Judiciary Criminal Committee, has introduced legislation, House Bill 5346, that would create a pre-trial mechanism for judges to consider the reliability of confession evidence and provide guidance as to the hallmarks of an unreliable confession. Under the proposed legislation, a judge could refuse to allow a confession into evidence if, for example, the confession fails to provide any new details to law enforcement, doesn’t line up with other evidence, or directly contradicts other evidence.

While Illinois has been a nationwide leader in wrongful convictions, the state has also been a leader and innovator in solving the contributing problems of wrongful convictions. In 2021, Representative Slaughter and his chief co-sponsor, Republican Minority Leader Jim Durkin, unanimously passed legislation to ban the use of law enforcement deception in the interrogation of minors — a first-in-the nation bill that has led to bans in Oregon, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Nevada, and Utah. Representative Slaughter’s work follows in the footsteps of former Illinois State Senator and U.S. President Barack Obama, who passed the first law requiring the video recording of interrogations in the country, leading the way for 33 other states to enact similar policies.

Illinois could become the first state in the nation to ensure reliability in confessions by passing House Bill 5346, and serve as a beacon to all other states when it comes to keeping unreliable evidence from factfinders. Together with recording interrogations and banning police deception to minors, this trifecta of reforms would bring to fruition a vision set two decades ago to prevent false confessions from ripening into harrowing and costly wrongful convictions.

Peter Neufeld is Innocence Project’s co-founder and special counsel. Steven Drizin is a clinical professor of law at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law and the co-director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.