- “Now that I’m aware of the whole dental world, I know I could have saved some of those teeth.”

Injustice Beyond Bars: How Poor Oral Health Care in Prison Continues to Burden Wrongfully Convicted People

“Getting my teeth fixed exonerated me in a different kind of way.”

03.20.24 By Alyxaundria Sanford

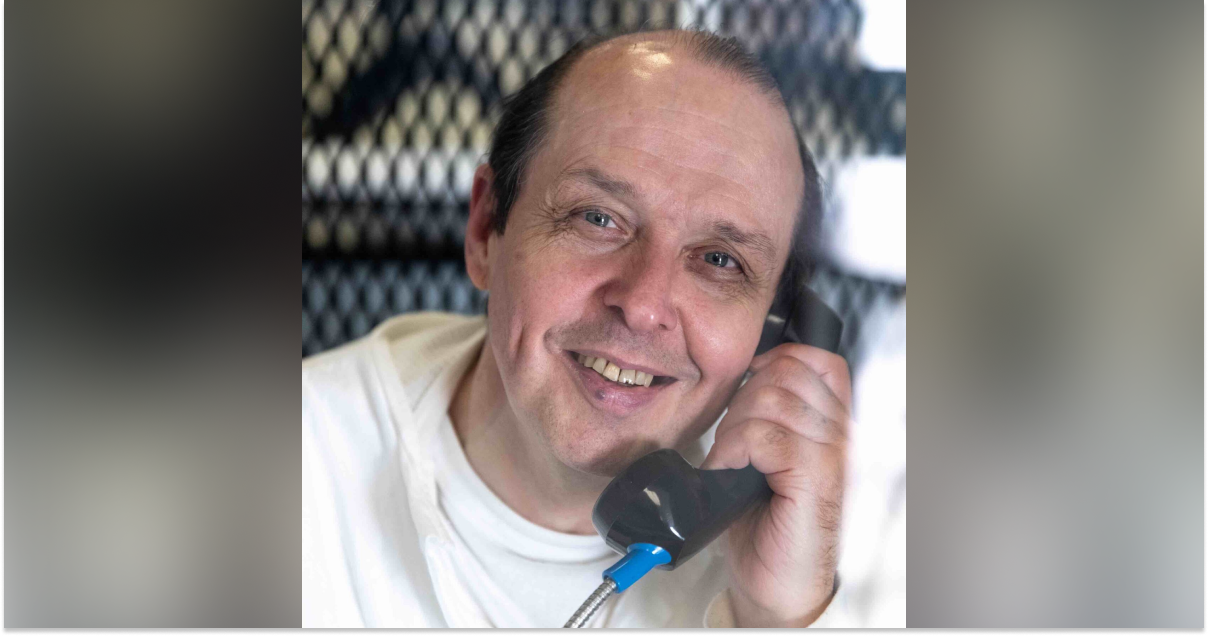

Rodney Roberts at the 2023 Innocence Network Conference in Arizona. (Image: Kenny Karpov /Innocence Project)

Rodney Roberts grew up taking care of his teeth — his mother instilled good habits from an early age — but found himself facing a dental nightmare when he was wrongfully incarcerated for 18 years.

Mr. Roberts describes the prison dental clinic as a “butcher shop,” recounting the “cruel and unusual” experience of having three teeth pulled for common cavities. Not only did he have to endure the pain of the extractions but the low-grade painkillers he was given made recovery unnecessarily agonizing.

“Now that I’m aware of the whole dental world, I know I could have saved some of those teeth,” said Mr. Roberts, now a re-entry coach at the Innocence Project. “They could have filled some of the cavities — capped or crowned my teeth — but I was never given that option.”

As a result, he avoided dental visits while in prison, causing his oral health to deteriorate over the years.

The poor quality, and often the brutality, of dental care has deep and lasting consequences for many people caught in the carceral system. Mr. Roberts attributes this to the inhumane treatment of people throughout the country’s prisons.

“It’s an extension of the mindset that you’re here because you’re being punished. They have to provide you with dental care. They didn’t say they had to provide an above-quality standard, as long as it’s dental care,” he said.

Mr. Roberts in 2022 preparing for bridge implants after the dentist noticed his fear and helped him relax. (Image courtesy of Rodney Roberts)

The Federal Bureau of Prisons’ policy on prison dental services corroborates that claim. It states that “dental care will be conservative, providing necessary treatment for the greatest number of inmates within available resources.” This limited approach to dental care even takes place on the state level. For example, the Florida Department of Corrections’ dental policy considers procedures such as crowns, bridges, and implants to be elective dental care, and the wait to see a dentist can be up to two years in some prisons.

While most correctional facilities initially provide basic hygiene products like toothbrushes, incarcerated people are expected to replace them by purchasing them at the commissary, an added expense on low wages.

Ummer Ali, a social worker at the Innocence Project, echoed that the oral health treatment people receive in prison is a reflection of the carceral system at large, sharing examples of the overlooked struggles faced by clients who have lost teeth in the time they were in prison or jail.

“I can go get a steak right now and there’ll be no issues. But for folks who are missing teeth or who have really bad dental health because of being incarcerated, they have to really think about how a meal could ruin their whole day,” Mr. Ali said, referring to several clients’ desire to eat at a steakhouse.

In fact, one client, who was waiting for his implants post-release, once choked on his hamburger so severely that a Heimlich maneuver was performed, according to Suzy Salamy, Innocence Project’s director of social work.

“His dentures never fit properly, even though he had traveled over an hour to his dentist nine times to get a better fit,” she said.

The consequences of poor oral health extend beyond physical discomfort. Mr. Roberts said that when he was released from prison, he felt a sense of shame and embarrassment due to the state of his teeth. He withdrew from social circles and mumbled through public speaking engagements.

“I was so self-conscious of what my smile looked like,” he said.

- “Something as simple as a smile can make you open up your shell.”

Mr. Roberts feeling confident after the dental procedure. (Image courtesy of Rodney Roberts)

That sense of embarrassment, coupled with the social stigma associated with neglected oral health, may be an added roadblock to chances of employment, especially in public-facing roles. According to the Prison Policy Institute, the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is a staggering 27%, more than seven times the national average.

When Mr. Roberts was finally able to see one particular dentist whom he described as compassionate, he said people noticed a change in his confidence.

“It wasn’t a personality hang up. Something as simple as a smile can make you open up your shell, because now you feel comfortable opening up your mouth,” he said.

In his role as a re-entry coach, mentor and advocate, Mr. Roberts says he wants to serve as a testament to the transformative power of a smile. With some dental bridgework already completed and the prospect of veneers on the horizon, Mr. Roberts is reclaiming not only his oral health but also his confidence and self-esteem.

“Getting my teeth fixed exonerated me in a different kind of way,” said Mr. Roberts. “I felt like I made parole from being held back by shame.”

While comprehensive treatment can significantly boost self-esteem and even opportunities, the costs can be tremendously high and a significant barrier to accessing essential care for many Americans. An estimated 68.5 million adults in the United States lack dental insurance. For those who have experienced incarceration, this financial burden can be insurmountable.

Currently, the Innocence Project’s Exoneree Fund, which is supported by generous donations, helps supplement the costs of crucial dental procedures that are not covered by insurance.

Additionally, Mr. Ali and his colleagues on the social work team have tapped into their personal relationships to connect clients to medical providers. He said he hopes that the process becomes more streamlined in the future, especially when it comes to oral healthcare.

“It’s easier for me sometimes to find a cardiologist than it is to find a dentist,” said Mr. Ali. “I think if we had a network of folks who’d be willing to do [cosmetic dental implant procedures] for some discounted rate, that would genuinely change so many people’s lives.”

Learn more about the Exoneree Fund and donate here.

Meghan Nguyen contributed to this report.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

March 23, 2024 at 7:39 pm

March 22, 2024 at 5:14 pm

Why not create a project to contact Dentists in each of your cities to donate, ‘ Floss, toothbrush , toothpaste’ to every prison throughout the world??

I am proud to donate to the Innocence Project. Mr. Roberts’ story is a testimony to why the work of the Project is so necessary. Thank you, Innocence Project, for your commitment to justice and human rights!