Ms. Swarns’ feature in the American Bar Association Journal in 2012. (Photo courtesy of Christina Swarns)

Named one of America’s top lawyers, Ms. Swarns has spent decades challenging injustice. Here’s how she got there.

02.25.25 By Alyxaundria Sanford

Christina Swarns didn’t grow up dreaming that she would one day become one of the few Black women to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, let alone win a precedent-setting case like Buck v. Davis, which struck down a racially biased death sentence. In fact, as a self-described shy and introverted child, she wasn’t even sure what she wanted to do career-wise. But life has a way of pulling people toward their purpose, and for Ms. Swarns, that meant becoming one of the most influential voices in criminal justice reform.

Now in her fifth year as executive director of the Innocence Project, Ms. Swarns has spent decades fighting to dismantle the many systemic failures that lead to wrongful convictions, especially for Black and brown people. Along with arguing before the nation’s highest court, she has overturned numerous death sentences rooted in racial bias, and led teams of attorneys at some of the country’s most impactful legal organizations, including the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and New York City’s Office of the Appellate Defender. Once dubbed “Lady of the Last Chance” by the American Bar Association Journal and named one of Crain’s Notable 2023 Black Leaders, she was most recently named to the 2025 Lawdragon 500 Leading Lawyers in America list.

But her story isn’t just about big wins — it’s about the path that got her there. In a recent interview, she reflected on her career, the lessons she’s learned, and the legacy she hopes to leave.

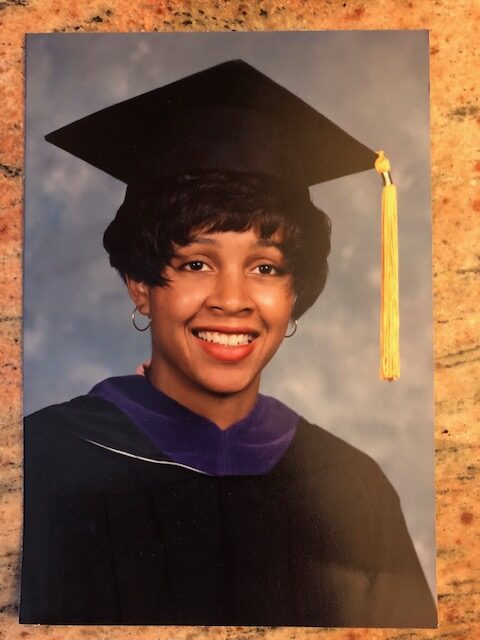

Ms. Swarns’ feature in the American Bar Association Journal in 2012. (Photo courtesy of Christina Swarns)

You’ve spoken before about a time in your life when you weren’t sure what direction to take and felt uncertain about your path. Can you share more about that period and how it shaped your personal and professional journey?

I grew up in Staten Island, New York, with a Caribbean immigrant mother who was a teacher and a father from North Carolina who worked in business. I had no idea what I wanted to do — for a while, I even dreamed of being a hairdresser. I eventually found my way to law but had little understanding of it since I had no direct access to lawyers or the legal world.

My knowledge was what I saw on TV. My mother said I had to have an internship that was relevant to my aspirations, so she made the effort for me and got me an internship through a neighbor two doors over, who happened to be a prosecutor. After working that internship for two summers, I enrolled into the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, knowing one thing and one thing only, that I would never do criminal law again.

I did very well in law school, but I actually graduated without a job which was unusual. At that moment it felt like things couldn’t get any worse. It felt deeply embarrassing to be in that position, but also empowering to have the time to figure out what I wanted to do.

Ms. Swarns graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School in 1993. (Photo courtesy of Christina Swarns)

Who helped you find your way during that time?

My sister, Rachel, suggested that I speak to lawyers to learn what they do day-to-day. I had a series of lunches which were informative. And at the same time, my parents said that I needed to at least volunteer. I knew I wanted to work with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. (Important note, I did not realize it was quite as prestigious as it is.) I picked up the phone and said, “Listen, I got some time on my hands. I have a good degree. And I’m free.”

Elaine Jones, who was the director-counsel of the NAACP LDF at the time, sat down with me, and she interviewed me and hired me as a volunteer. She gave me options of which divisions I could work in: political participation, education, economic justice or capital punishment. I told her I’d go anywhere. And she sent me to work in capital punishment. That was my first experience in criminal justice from the defense side. And I loved it.

But for many years I didn’t tell this story. I had a lot of imposter syndrome and felt like I had snuck in the backdoor.

As one of the few Black women to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, how has your identity impacted your work? Did you take that with you in the courtroom?

Always. The Supreme Court [Buck vs. Davis] case was all about race, and the perceived link between race and criminality, race and violence. For me, it was important that I stood and argued the case because I really viewed myself as a living refutation of what was happening in this case. You can’t talk about Black people being more likely to commit crimes as I stand here, arguing in the highest court in the land. I’ve overwhelmingly represented Black men, and, since I was 27, I overwhelmingly represented people convicted of murder.

I bring my identity with me to strengthen relationships with my clients. I can call out things in ways others may not feel comfortable. I can say, “You and I come from the same places, and so we’re not going to play that nonsense.” I can get to a different place. [My identity] is a shorthand that helps build relationships.

Whom do you draw inspiration from in the fight for justice?

I’m a big fan of Ida B. Wells, because she documented hundreds of lynchings. I spent many years fighting death penalty cases, so I’m humbled by so many things about what Ida Wells did. I can’t even imagine how she did that at the turn of the century, documenting and telling the stories of people who were lynched. I can’t even imagine the depth of commitment and the personal risk that it took to do that.

I am also a huge fan of Fannie Lou Hamer and love her quote: “If I fall, I’ll fall five feet four inches forward in the fight for freedom. I’m not backing off.” And coincidentally, I’m 5’4”!

What challenges have you faced in advancing anti-racism?

Race is hard to talk about. Usually the first challenge is understanding why we have to talk about it. Which is another way of saying: I’m afraid to talk about [race]. The initial challenge is creating a safe space to have the conversation. But there’s no way, especially in the criminal legal system, we cannot talk about race because they’re inextricably tied to one another. People are so afraid of the fault lines, of saying the wrong thing and being canceled. It’s tragic because then we never get to the heart of the real issues.

Looking back, what moments have been the most meaningful for you?

One of the most special moments was the day Jabar Walker joined us for an all staff meeting after he was exonerated. Jabar shared his experience and described just how hard it was for him to live through his incarceration. And then somebody said, Well, what do you want now? And he said, I just want a hug. And there was a line that went out the door of the staff who stood up to give him hugs. That lives in my heart. Another proud moment was sitting in the well of 100 Center Street and watching Vanessa Potkin and Barry Scheck help exonerate Muhammad A. Aziz, who was wrongfully convicted in the 1965 murder of Malcolm X. It was amazing to be part of that history and watch him be exonerated.

How do you balance the emotional demands of your work with your well-being?

That’s hard. When I was in Philly, I was a federal defender, doing capital punishment work for seven years. I had a really high volume of cases, about 20 death cases at any given time. Because I spent a lot of time just in really sad spaces I remember feeling like I needed everybody I knew to just come over and be nice to me. To cope, I joked and told people I was going to take a vacation or walk around Barney’s [department store]. I wanted to spend some time in a world where people were just looking at sparkly things.

It became really important for me to have balance in my life. So, to this day, I have a whole world of friends that have nothing to do with criminal justice.

What legacy do you hope to leave as the Innocence Project’s executive director?

I would like to end wrongful conviction in this country. It’s not going to happen on my watch, but I hope to advance the ball. Another thing that is important to me as a leader is that people feel as though I ran an organization where the staff can genuinely flourish. It’s really important to me that this is a place where you can live and do really hard and amazing work and not be overwhelmed or burned out.

When I was younger in college, I was smitten by the title of Huey Newton’s book: To Die for the People. I thought that was the grandest thing. I totally used to be like, “Yes, the goal is to die for the people.” But as I’ve grown, I realize that the goal is not to die for the people but to live for the people. And that’s what I want. I want this to be a place where people are able to commit to this extraordinary cause and live whole and full and healthy lives. We should be able to do this work that is going to require a lot and go home and watch 90 Day Fiancé.

How do you see your role in inspiring and mentoring the next generation of Black attorneys and justice advocates?

We end where we started. I know what my bio sounds like but I don’t want to feel inaccessible. I want people to understand that you can do what I do. It is all about finding your love, passion, and place. And once you find that, you can do everything that I did. You just have to be willing to make the sacrifices for it.

The instinct is to hear that I argued in the Supreme Court and I run the Innocence Project, and blah, blah, blah, and the LDF — and immediately there’s this monster pedestal, this big separator. And I’m like, “No, please don’t put me on a pedestal. Instead, I want you to understand that I have walked behind you. I have walked with you, and you can walk the same exact walk.” And that, to me, is the most important thing.

*This Q+A was edited for clarity.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.