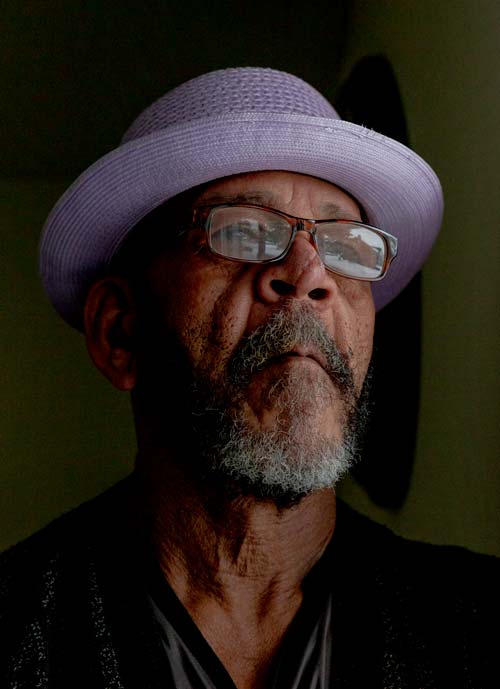

Gerry Thomas, 64, at his apartment in Sterling Heights, Michigan on Feb. 7, 2022. (Image: Sylvia Jarrus/Innocence Project)

Special Feature 02.16.22 By Daniele Selby

Gerry Thomas shows an old photo of himself as a 14-year-old inside of his apartment in Sterling Heights, Michigan, on Feb. 7, 2022. (Image: Sylvia Jarrus/Innocence Project)

“I have always loved making stuff,” said Gerry Thomas. “Even back in the day, before I went to prison, I was pretty crafty with my hands, and I loved it especially because I wasn’t so good at school.”

As a youth in Detroit, Mr. Thomas built mini bikes, fixed up cars, and enjoyed helping his brother repair houses. And liked to play around with his style, “jazzing up” his clothes.

“My mother would say, ‘Boy, you done messed them clothes up.’ But I ain’t really messed them up, I just put them the way I like,” he recalled.

He didn’t give his creative hobbies much thought beyond that, but in 1991, when Mr. Thomas was wrongly convicted and incarcerated for an assault and attempted murder in Detroit, his passion for creating and crafting with his hands became his lifeline — his one freedom within the extremely restrictive conditions of prison.

He spent nearly 30 years wrongly incarcerated before being exonerated in January 2020. At the beginning of his wrongful imprisonment, he struggled to hang on to the mantra his mother instilled in him: “Always keep love in your heart.”

“Imagine, you’re a grown up, but you’re treated like a little kid and you have all these restrictions — you can’t do this or that — and you have to obey someone that you don’t know and you’re innocent,” he described. “I just really had to do something, so I just started making stuff.”

Mr. Thomas said he drew strength from creating something — anything — every day, calling it “spiritual food.” He said doing so encouraged him to “just keep moving, keep good thoughts in my head.”

He began by learning leatherworking from another incarcerated man who made moccasins and sold them to others in the prison. The men would pay for the shoes in the form of items from the commissary. Mr. Thomas quickly became adept at making shoes, and with encouragement from his friend began experimenting with making leather goods of his own design.

Soon, men in the prison began commissioning items from him. Even prison officers took notice of his work and asked him to make them leather goods for their own use.

“Once I got a little more material, I just went wild with it,” he said. “And people loved what I made, they would say, ‘This is exactly what I wanted — don’t you make another one of these for anyone else!’”

Mr. Thomas made several belts with different designs, a modest accessory that allowed him to “jazz up” his prison-issued clothing, making it ever so slightly unique. But in 1998, the prison prohibited the men from using their own personal belts. Instead, they were given standard belts that were rendered unnecessary a short while later by prison uniforms with elastic waistbands.

Mr. Thomas would not let his creativity — one of the few things he had control over in prison — be stifled. He made other items, like bags and wallets, sometimes embossing and painting them with floral designs and bright colors throughout his 10 years at that prison. His passion helped him earn some money, most of which he put back into his hobby, and it helped him “keep love in my heart.”

Gerry Thomas at home in Sterling Heights, Michigan, on Feb. 7, 2022. (Image: Sylvia Jarrus/Innocence Project)

“Then they unplugged me,” Mr. Thomas said. “Unplugged” is what he called being transferred to another prison. The next prison had stricter regulations and did not allow incarcerated people to have access to leatherworking tools. Mr. Thomas had to put his leatherwork aside.

Working with his hands was the way Mr. Thomas hung on to freedom — if he could have no other form of freedom, then he could at least be free to create. And when he couldn’t do even that, he leaned on his “strength box” — his cassette tape player and small trove of gospel tapes and recordings of speeches by Martin Luther King Jr.

Mr. Thomas was a child at the peak of the civil rights movement, but even then, Dr. King’s words resonated with him. Mr. Thomas attended a segregated school and lived in a poor, primarily Black neighborhood in Detroit, where from an early age he was cautioned to be vigilant against the city’s rampant violence, but, at times, it was unavoidable.

In his 20’s, Mr. Thomas worked as a maintenance person in an apartment building in what he called a “bad area.” In his time working there, he found several bodies of people who had been killed in the common areas. He was later shot by a resident of the building and seriously injured, having to use a wheelchair for some 30 months as a result of his injuries. The man was never arrested or thoroughly investigated. The man was found dead a few years later. He had been tied to a tree and shot.

In 1987, a Black woman was threatened at knifepoint and sexually assaulted in her car while waiting for her son to come out of a convenience store. She was forced to drive the car with her attacker — who she described as Black man with a “dark complexion” and beard, and said he was taller than herself, roughly 5’ 3”. Eventually, she escaped and the man drove off with her car.

Police pulled two people over in the woman’s stolen car three weeks later. The passenger told police that they’d gotten the car from the driver’s relative. The men in the car were released after the woman did not identify either of them as her attacker. Even though police had found the woman’s vehicle registration at the driver’s home and the driver’s relative matched the woman’s description of her attacker, the police did not question the relative. In fact, they conducted no further investigation.

Gerry Thomas, 64, at his apartment in Sterling Heights, Michigan on Feb. 7, 2022. (Image: Sylvia Jarrus/Innocence Project)

Two years later, the woman thought she spotted her attacker walking out of a store. She drove to her sister’s house and returned to the store with her husband. The officers who met her there searched for the man she’d seen and a few blocks away encountered Mr. Thomas. The woman identified him as the man who had attacked her, but police did not arrest him nor did they investigate the case further.

The police returned eight months later and arrested Mr. Thomas solely on the woman’s identification — eyewitness misidentification is the leading contributing cause of wrongful convictions. No physical evidence connected him to the crime and his light complexion and towering frame clearly did not match the woman’s description of her attacker.

The shoddy police investigation that led to Mr. Thomas’ wrongful conviction is an example of the ineffective and lackluster policing reported by communities of color, especially poor Black communities. Research shows that, although Black people are disproportionately victims of crime, crimes against Black people are less likely to be cleared by police, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, and murders involving Black victims are less likely to result in an arrest.

Despite obvious gaps in the investigation of Mr. Thomas’ case, he was convicted and lost nearly three decades of freedom. Black people exonerated from sexual assault convictions, like Mr. Thomas, spend an average of 4.5 years longer in prison before being exonerated than their white counterparts, the National Registry of Exonerations found.

In prison, Mr. Thomas returned to Dr. King’s words over and over.

As an innocent person in prison for a crime he didn’t commit, Mr. Thomas said, Dr. King’s words took on even deeper meaning because of the civil rights icon’s own unjust incarceration.

I was determined to come out of that prison standing up.“MLK said in ‘65, ‘No lie can live forever,’ and I really believed that,” he said. “I was determined to come out of that prison standing up, I said, ‘I am going all the way to the resting place standing up.’”

He said the voices of his loved ones, Dr. King, and gospel singers like Mahalia Jackson and Shirley Caeser would come to him in difficult times giving him a “strength of spirits.”

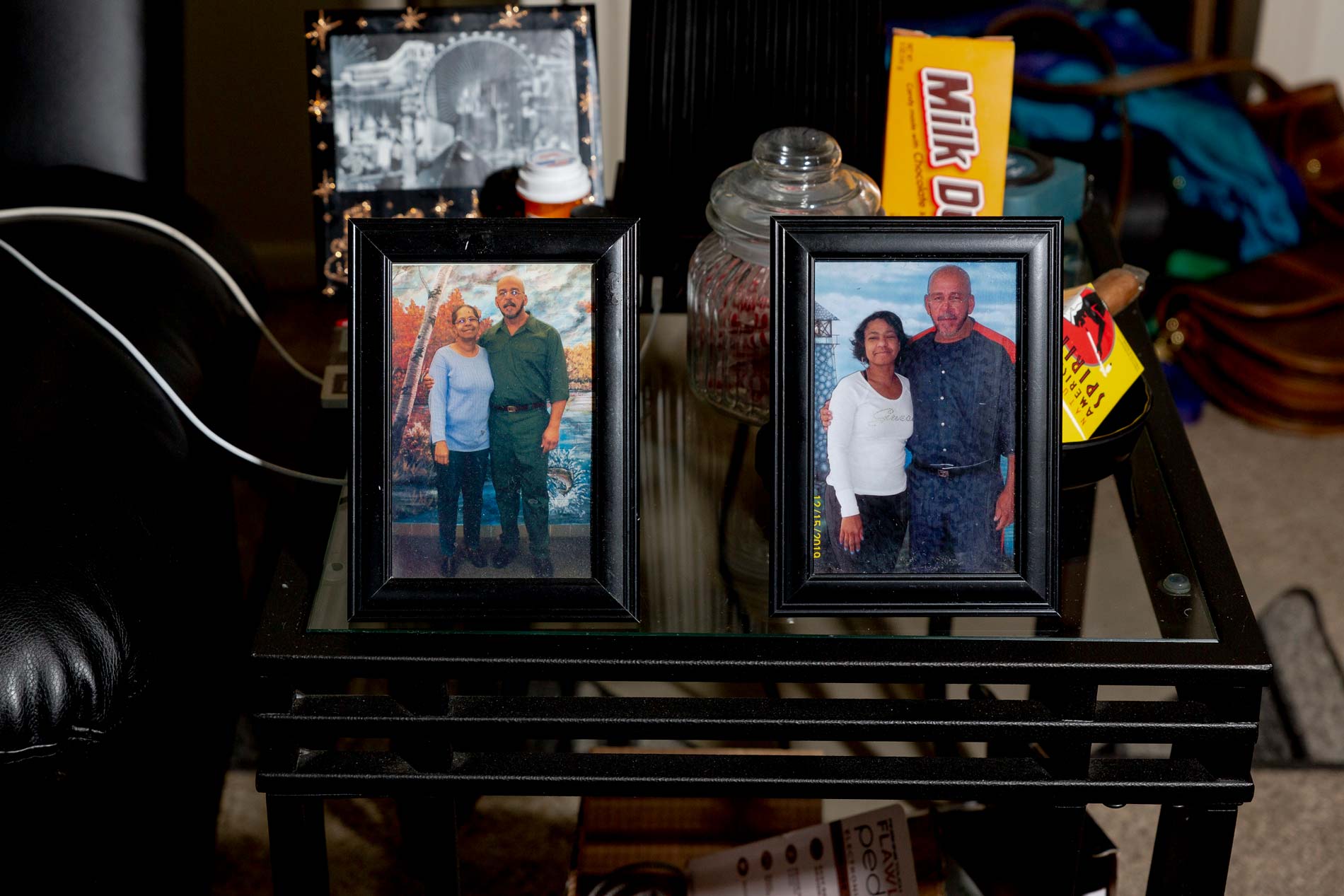

Photos of Gerry Thomas with his sister (left) and niece (right) while he was in prison sit on a table in his apartment in Sterling Heights, Michigan on Feb. 7, 2022. (Image: Sylvia Jarrus/Innocence Project)

A clock Gerry Thomas made for his Innocence Project attorney Jane Pucher during his wrongful incarceration. (Image: Innocence Project)

“Every day of that 30 years in some kind of way I felt that strength [of spirits] and I had to keep going because if I’d have stopped I’d have been gone right now. Any time a heavy or sad thought came to me, I’d hear like, ‘Hold on, don’t stop there,’” Mr. Thomas said.

And so he didn’t.

At the prison where he spent his final years of wrongful imprisonment, Mr. Thomas could not do any leatherwork. Instead, he turned to making clocks, cards, and art with the few tools and resources he had.

Deprived of sandpaper to smooth out the edges of the intricate clocks he fashioned from craft sticks, he devised his own sandpaper, gluing sand from the prison yard to a piece of paper. But when an officer discovered his homemade sandpaper, he threatened to send him to the hole — solitary confinement — but ultimately told him he’d let it slide as long as he threw the sandpaper out because he’s a good guy.

Mr. Thomas’ next solution: an “itty bitty” rock. Day after day, Mr. Thomas placed the small rock, perfect for sanding down the edges of the craft sticks he cut down and shaped and with nail clippers, in the same spot so that it would be there when he needed it for his next project. And though working with leather is his main passion, Mr. Thomas said the clocks he made with these limited tools for his Innocence Project attorney Jane Pucher are some of his proudest pieces.

Gerry Thomas and his sisters Lois and Mary moments after his exoneration and release from 29 years in prison on Jan. 13, 2020. (Image: Suzy Salamy/Innocence Project)

In January 2020, Mr. Thomas was freed and fully exonerated after a reinvestigation into his case by the Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) of the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office confirmed what he’d always said: He was innocent.

Mr. Thomas has returned to the words of Dr. King many times since being freed. “The stuff he talked about is happening still today even though that person is long gone,” he said a year after his exoneration.

Segregation in Detroit officially ended in the ‘70s, but its impacts continued to be felt by the city’s majority-Black population. Black communities in Detroit are still experiencing higher rates of poverty and inadequate access to necessary resources like quality health care. These disparities have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In these ways, segregation persists in the city, though its taken on a different veneer, Mr. Thomas described. His own neighborhood was classified by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, as “highly segregated.”

One study found that Detroit remains one of the most segregated cities in America. The city has even retained a wall from the era of segregation that divided Black and white neighborhoods and stands as a controversial reminder of the racist policies of the past.

But Mr. Thomas said he continues to live by his mother’s words, “For the rest of my stay here on earth, I’m just going to try to keep love in my heart and go from there.”

His main goal is to make people happy.

“I always tell people, before I leave, Imma have you laughing — and sometimes just that makes them laugh, and then it makes me laugh because I’m making someone happy whether they’re in the supermarket or wherever, going through something bad.”

And he is most excited to get back to leatherworking now that he has unfettered access to tools and materials that he couldn’t get while incarcerated.

“I just see different [after being exonerated],” he said. “I feel like we’re not here forever, so we just have to make the best of what we’re doing. I don’t want to be at the end of the road [of life] and be like ‘Man I wanted to do this, I wanted to do that’ — so I want to do all I can do.”

While he hasn’t gotten his hands on any leather materials yet, Mr. Thomas has been tinkering with an old Cadillac and has plans to build a lamp using an empty champagne bottle. His day is filled with the sounds of Motown and gospel classics — his “soothers” — that play from a little monkey-shaped bluetooth speaker that he wears around his neck. And his love of style has been restored.

“I just want to grab ahold to everything I can and be very happy,” he said. “I hope that if people I’ve met remember me for a minute, they say, ‘Man, that guy was so good.’”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.