Worlds Collide: How Two Leaders’ Experience of Childhood Segregation Led Them to Criminal Justice

Innocence Project Executive Director Christina Swarns and Board Member Denise Foderaro discuss their paths.

03.31.21 By Innocence Staff

Christina Swarns and Denise Foderaro are powerful advocates for justice — Christina as the executive director of the Innocence Project and Denise as an Innocence Project board member and the co-founder of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice.

They grew up in very different, but similarly segregated neighborhoods — Christina in a Black neighborhood in Staten Island and Denise in an all-white inner city neighborhood of south Philadelphia — in a time of racial and political tumult. Their childhoods had profound and lasting effects on their individual views of the world.

Despite those differences, the two found that they share more in common than either would have guessed.

And though they took very different roads to careers in criminal justice reform — Christina was inspired by an internship at the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., while Denise was motivated by her husband’s wrongful conviction — their unique perspectives have inspired powerful advocacy.

During Women’s History Month, they came together over zoom to discuss how their formative experiences led them to these paths.

Denise Foderaro with her siblings (Image: Courtesy of Denise Foderaro)

Denise: I grew up in a Catholic family, in an Italian neighborhood in Philadelphia, where we were told we weren’t allowed to venture into neighborhoods with people of different races and nationalities. So I first met kids from my outside of my neighborhood when I participated in a summer program run by the Archdiocese called Operation Discovery, which brought young kids from different races and neighborhoods together.

I had an incredible experience with kids of color who I would have never otherwise met. Looking back on it, even though everybody was a different race or religion, they became friends. It was a beautiful experience because kids approach things differently and as a young child, I was more curious than anything else.

Christina: Denise’s description of her childhood sounded exactly like mine. She was one of five kids, I was one of three. I grew up in a working middle class household in Staten Island. We had a dog. We played outside.

But we were the first Black family to move onto my block.

Denise: Did you feel welcome on that street?

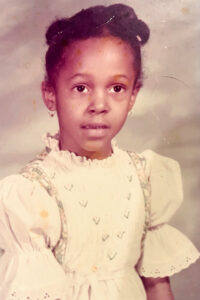

Christina Swarns as a child. (Image: Courtesy of Christina Swarns)

Christina: Not at first. Nothing bad happened to my family, but I definitely didn’t always feel welcome.

At that time, there were hard borders between neighborhoods that corresponded with race. I remember thinking that there were “zones.” “Neutral zones” were neighborhoods where it was safe for me, as a Black person, to go. “White zones” were neighborhoods where I understood that I could never go without facing physical danger or racist taunts.

My neighborhood was considered a “Black zone,” even though it was a mixed community — again, we were the only Black family on our block. I guess it was like a “one-drop rule” — it was designated a Black community if any Black people lived there. Eventually, a couple of additional Black families moved in.

I grew up thinking that these racial borders were normal. I didn’t realize that this was a crazy way to live until after I left.

Denise: It was scary back then. I remember race riots. I was young and it was scary because we had a similar racial divide line in the playground.

I remember being in that wonderful summer program. It was different from my usual school because, there, I had Black friends. We did plays together and we had fun but I knew that I could never take them to my neighborhood. And they couldn’t take me to theirs either.

Denise Foderaro as a child. (Image: Courtesy of Denise Foderaro)

That said, one time, I brought one of my Black friends to my house. My father wouldn’t let her come in and it was awful. I felt terrible and my father and I didn’t speak for a while afterwards. Part of it was the time and the tumultuous awfulness, but somehow we got through. Later in life he evolved and had Black friends and co-workers.

Christina: I had that happen to me too. I went to a friend’s house and I was asked to leave. My friend was mortified and I left because I didn’t want to cause a problem. I forgot all about that until you shared your story.

Denise: I hurt for this country now and what it’s going through. My generation wanted a better world; we protested the Vietnam War. I thought we made so much progress. But it’s clear we still have a long way to go to address discrimination, especially in the criminal justice space.

Christina: When I was younger, I didn’t think of criminal justice as a racial justice issue. I didn’t have any contact with the criminal justice system until I interned at a prosecutor’s office when I was in college. They were incredibly kind to me — I was the only non-law student and I had no relevant skills. But I saw an overwhelming number of Black people coming through the system and I found it impossible, as a Black 19-year-old, to stand on the opposite side of the courtroom. So, for the duration of my internship, I worked to avoid public-facing positions.

Christina Swarns’ graduation photo. (Image: Courtesy of Christina Swarns)

After that experience, I thought I’d never work in criminal law but I wound up volunteering at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and that opportunity gave me a completely different perspective on criminal justice and brought me back to this field.

Denise: I became involved in criminal justice after my husband was convicted even though he was innocent. It was like, here we are, two college graduates, we speak English, we had money, we had good lawyers, and we still lost and it was crazy.

After that, we felt like we had to help people who couldn’t help themselves. That’s how we got involved with the Innocence Project.

Since then we’ve heard terrible story after terrible story, and it’s clear that there is a big problem, that this system is incredibly problematic. You know, in other fields — like transportation or medicine — when mistakes are made, there is accountability. It doesn’t take 20 years to fix the problem.

So when someone says that the release of someone wrongfully convicted shows that the criminal justice system worked — I don’t agree. If you put your key in your car ignition for 20 years and it didn’t turn, and suddenly it works, I don’t think you’d say your car is working.

Christina: Exactly! Once I saw the problem — it’s breadth and scope — the unchecked power without accountability; the fact that people are just being churned through without regard for humanity, I thought we can’t just keep pretending it’s okay.

This system is broken and it corrupts everything. It even corrupts the way we look at each other. For example, as I look at you, Denise — if you put the two of us on stage and said one of us had a personal experience with the criminal justice system — the expectation would be me. And the reality is that so many people have this experience across the country.

Once you see how badly the system functions, there’s no turning back.

Denise: I agree, it’s about our humanity. We just have to help other people and liberate them in more ways than one.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.