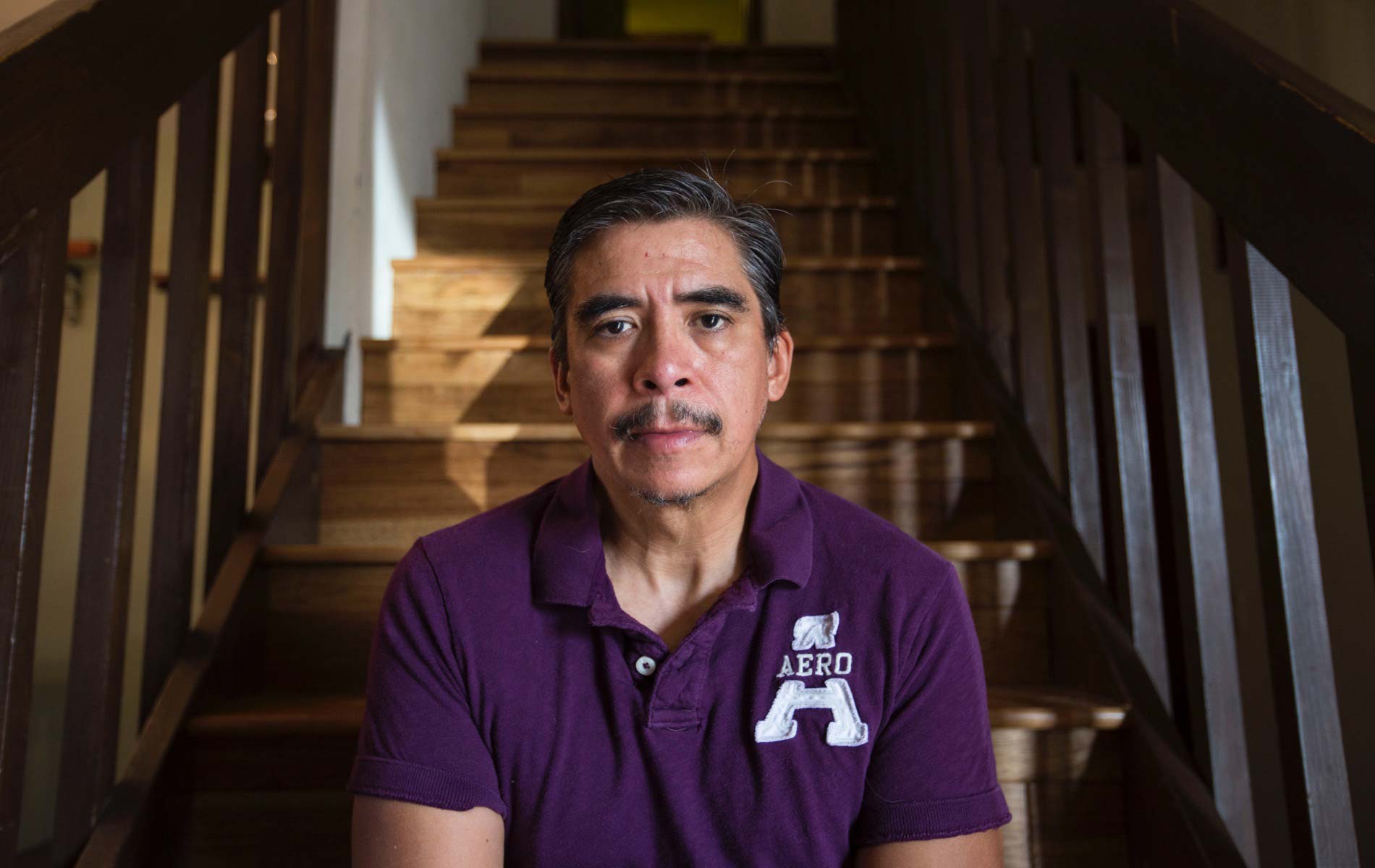

Floyd Beldsoe will be working with the Innocence Project in the coming year to get a compensation statute passed in Kansas. Photo: Erin G. Wesley.

In 2004, the Innocence Project ambitiously embarked on what was then unexplored territory for the then-young organization: criminal justice reform. The driving force behind the policy-based work was the organization’s firm belief that remedying systemic failures couldn’t be met solely by exposing miscarriages of justice; real transformation would require legislative action.

01.18.18 By Carlita Salazar

Floyd Beldsoe will be working with the Innocence Project in the coming year to get a compensation statute passed in Kansas. Photo: Erin G. Wesley.

But from the very beginning of these efforts, it was clear to the Innocence Project that to be fruitful in this arena, the organization’s approach would require more than simply presenting solid facts and figures; it would demand persuasive stories that would touch both hearts and minds. It would require face-to-face interaction with the very people most vested in changing the laws: individuals who’ve lived through a wrongful conviction.

Over the past 13 years, the Innocence Project has partnered with dozens of people who’ve been exonerated of crimes they didn’t commit to convince state and federal lawmakers that they need to pass laws that will prevent wrongful convictions. These powerful partnerships led to the adoption of more than 100 criminal justice reform laws across the country.

In celebration of the Innocence Project’s 25th anniversary, the Innocence Project in Print spoke to three exonerees—Floyd Bledsoe, Kristine Bunch and Chris Ochoa—who are boldly speaking out about the injustices that they’ve suffered and are pressing lawmakers to pass legislation to prevent others from becoming victims of a broken system.

In late 2015, Floyd Bledsoe was exonerated in Kansas of the sexual assault and murder of his 14-year-old sister-in-law. He had been wrongfully convicted of first-degree murder in 2000 based on false testimony provided by his brother Tom at trial that contradicted an earlier statement Tom had given police in which he confessed that he himself had committed the crime. Tragically, the investigators chose not to record Tom’s confession, so there was no evidence of it to present in court. The jury was convinced by Tom’s testimony, and Floyd was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

Bledsoe advocating for compensating the wrongly convicted at a hearing in Kansas.

Fifteen years later, after the Midwest Innocence Project helped uncover exculpatory DNA evidence and Tom—in a suicide note—took responsibility for the crime, it was finally revealed that Floyd was, in fact, innocent. His case received loads of media attention and served as an example as to why it’s absolutely critical that law enforcement record interrogations in their entirety.

To prevent others from facing the awful injustice that Floyd suffered, in 2016, Representative Ramon Gonzalez—previously an investigator on Floyd’s case who also helped expose the wrongful conviction—introduced a recording of interrogations bill in Kansas. Initially, both prosecutors and law enforcement associations came out against the bill. But over the course of the months that followed, and in no small part because of Floyd and his story, many of the naysayers rallied around the bill in 2017.

As Innocence Project Legislative Strategist Michelle Feldman explains, “Floyd had a huge impact.”

In conversation with Bledsoe and policy strategist Michelle Feldman

—

Michelle feldman: It took time to pass a recording of interrogations law in Kansas. The bill didn’t pass the legislative committee the first year, but it did get referred to the judicial council.

That council met several times during the legislative recess. Floyd came with me to some of those meetings. He had a huge impact.

He spoke to one of the prosecutors—the leader of a prosecutors’ association—about his case. That was key. His story convinced her that if this recording law had been in place when his sister-in-law was killed, he may not have been wrongfully convicted.

Also, one of the lobbyists there got to know Floyd. It was so helpful for them to have a face—a real life person—to connect to the issue.

With that momentum, this year, we got a recording of interrogations bill passed that everyone was happy with.

Floyd Bledsoe: I felt honored to be able to partner with Michelle and the Innocence Project. I was very happy to be a part of it. I want to help those that aren’t able to go before senators and representatives and plead their cases.

In my case, it wasn’t that law enforcement didn’t have the capacity to record. The fact was that they chose not to record. And when I was in front of the Senate and the representatives, that’s what I told them.

I told them that I wasn’t there to talk about the law enforcement offices that don’t have the funds or capacity to record. I was there to speak to what happens when officers have the option to record interrogations and, yet, consciously choose not to.

In my case, the officers chose not to record my brother’s confession. Every one of my interviews with the police was recorded, but for the first 60 days of the investigation, my brother’s interrogations weren’t recorded.

If there had been a law that mandated that all of the interviews be recorded, it would have helped significantly in my trial. Rather than relying on the officers’ vague recollections, we could have had actual recordings of what was said. We would have been able to play those recording for the jury and the media so that everybody would have heard my brother’s confession.

For this reason, we needed a law that would require law enforcement across the state to record interrogations in their entirety.

One of the biggest arguments from opposing law enforcement has been that recording interrogations will undermine people’s confidence in law enforcement if they learn their interrogation tactics. But that’s only going to happen if officers aren’t following the law and doing what’s right. Otherwise, it’s only going to reinforce the best ideas of law enforcement, that they’re acting with integrity and not doing anything shady.

For me, addressing the lawmakers was a terrific experience. I was amazed at how open they were to receiving my story. They had a real willingness and desire to help. They were open and willing to listen to try to understand and to try to keep further wrongful convictions from happening.

I think their response speaks to the unique value that people who’ve been wrongly convicted—people who are personally vested in improving the system—can bring to spurring meaningful criminal justice reform.

Exonerees, just through their experiences, bring home the reality of wrongful conviction. It’s not just a news story or character on TV.

It’s not just a fact or figure from a piece of paper that someone is reading. When an exoneree is in the room with you—right before you—the reality of their stories and experiences and of the system’s failures cannot be denied.

Just like with many things, wrongful conviction doesn’t affect a person until they’re confronted with the issue, face to face, and then they can’t deny the truth of the matter.

For a long time, Kansas was able to say, “We’ve only had six wrongful convictions come to light. It’s just a few people out of hundreds of thousands in the system.” But when you have a living, breathing person whose been wronged by the system sitting right in front of you, it’s hard to deny that even one innocent person being wrongfully convicted is a real injustice.

I will most definitely continue partnering with the Innocence Project on policy-related work. One issue we’re working on is getting a compensation statute for the state of Kansas. After being exonerated, I was released and left with nothing. I’d lost my land, my farm and my family. There needs to be an automatic process for people like me who’ve been exonerated of wrongful convictions to receive the financial resources we need to rebuild our lives. Also, I’d like to see some policy reform to address prosecutorial misconduct.

It’s amazing to play a part in bringing about these types of changes.

Kristine Bunch was exonerated in 2012 of setting the fire to her home that led to the death of her three-year-old son Anthony. In the past year alone, she’s testified before legislators in Wyoming and Illinois about her case. Also, with exoneree Juan Rivera, she’s launched Just Is 4 Just Us, a nonprofit organization aimed at providing people recently exonerated and released from prison with practical resources and support to build their lives. And in September, Justice for Miss America, a book about her life and case was released.

“I can’t see myself ever turning down the opportunity to tell lawmakers how we can make life better for people who’ve been wrongfully convicted,” says Bunch.

Kristine Bunch recently started her own non-profit organization Just Is 4 Just Us. Photo: Narayan Mahon.

Kristine Bunch: I’ve spoken to lawmakers in Illinois and Wyoming. I think it’s great to put an actual exonerated person in front of legislators so that they can learn more about the experience of being wrongfully convicted. It gives them a face for the issue, and that’s very important.

That being said, it’s important to stay strong when doing this work because it can be very frustrating. There are a lot of hoops to jump through to bring about legislative change. I think these changes should be black and white. We need to open up the doors and make the changes. So, even though doing policy work has been a positive experience, it can also leave a person feeling deflated when you walk out and feel like you haven’t made a difference.

In Wyoming, I recently spoke about the need for compensation as well the need to get rid of the law that allows people only two years after being convicted to present new evidence to prove their innocence.

I decided that this law was important because in my case— and I’m sure the same is true for many people in Wyoming—it took me years to prove my innocence. In fact, I didn’t go for my evidentiary hearing in Indiana until 12 years after I had been wrongfully convicted. Sadly, in Wyoming, they have a two-year time limit for new evidence. If there had been a time limit in the state of Indiana, like there is in Wyoming, I’d still be sitting in prison, innocent, with no way to get back into court to prove it.

So, in Wyoming, I spoke to legislators about the critical need to remove the time limit. After I testified, four legislators came out to hug me. They told me that they understood why it was so pressing to get this bill passed.

But, ultimately, they wanted to table the bill and make some changes to it. I understood their need to get a solid version of the bill passed but I also felt like it should have been at the top of their agenda and that there should have been greater urgency in getting it done.

In Illinois, I spoke with legislators about the need for compensation because I’m from Indiana—a state that doesn’t have a compensation statute. One of the problems in Indiana is that compensation for exonerated people has become a partisan issue. It needs to become a more personal issue. Lawmakers need to realize that wrongful conviction can happen to anyone.

Truthfully, if I didn’t have a brother who took me in after I was exonerated and released from prison, I would be living on the street. I’d be in a shelter. I walked out of prison with a plastic bag containing my prison uniform and tennis shoes. I didn’t even have a toothbrush when I walked out. That shouldn’t be. And it’s not just a matter of compensation. It’s a matter of giving people the tools they need to rebuild their lives.

“I walked out of prison with a plastic bag containing my prison uniform and tennis shoes. I didn’t even have a toothbrush when I walked out. That shouldn’t be.”

“I walked out of prison with a plastic bag containing my prison uniform and tennis shoes. I didn’t even have a toothbrush when I walked out. That shouldn’t be.”

Kristine Bunch Photo: Narayan Mahon.

There are so many needs that exonerees have when they get out—mental and medical health care, interview preparation and career counseling, money for an apartment and a car. Compensation needs to entail a total package.

It’s more important for female exonerees to step up and talk to law makers about these issues. There aren’t a lot of us, but we’re out here, and we have needs that are unique to us.

I lost 17 years of my life. When I walked out, I wanted to have another baby. Fortunately, I had people step up to support me in that process. I saw a doctor who educated me about the options at this point in my life. So, it’s important for compensation packages to also address of the specific needs that exonerated women are going to have once they’re released from prison.

Also, women aren’t the typical exonerees sitting in front of legislators. When we do speak up for change, legislators reflect differently on the issues. They think, “That could have been my sister. That could have been my aunt.” It makes the issue more personal for them.

Any time that I’m asked by the Innocence Network to go speak, I’m going to show up. I can’t see myself ever turning down the opportunity to tell lawmakers how we can make life better for people who’ve been wrongfully convicted. I have insider information; I can let them know things that they can’t see or experience for themselves. I feel like we’re making changes.

Amshula Jayaram is one of the Innocence Project’s state policy advocates. Her job is to foster relationships with lawmakers and other public officials for the purpose of educating them about how they can help prevent wrongful convictions through legislation.

One of Amshula’s greatest successes has been in Colorado. There, she collaborated with state policymakers to get a law passed mandating the recording of police interrogations in order to prevent false confessions.

Amshula, however, will be the first to say that she didn’t do it alone.

Key to the Innocence Project’s success in Colorado was the story and experience of Chris Ochoa. He spent 13 years of his life in prison for a wrongful rape and murder conviction.

Chris Ochoa in Wisconsin in 2016. Photo: Saiyna Bashir.

In 2002, with the help of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, he proved his innocence and was exonerated. One of the factors that contributed to Chris’ conviction was a false confession that was coerced by the police. Had the confession been recorded, it’s possible that neither Chris nor his co-defendant, Richard Danziger, whom Chris implicated in his confession, would have been wrongfully convicted.

To help get the law passed in Colorado, Chris leveraged his unique and painful experience to convince lawmakers that Colorado needed to pass a statute mandating the recording of interrogations. As Amshula explains here, Chris’ voice made all the difference in getting the bill passed into law.

Amshula Jayaram testifies before legislators in Colorado in 2014. Photo Gary Stefanski.

Amshula: When I started working in Colorado, the state had a post-conviction DNA testing law and a preservation law but nothing that looked at the front end of the system. Also, the attorney general’s office had received a grant to look at old cases to determine whether there were any wrongful convictions. And there was the exoneration, subsequently, of Robert Dewey.

The Innocence Project’s goal was to get two new statutes passed. The first campaign was on eyewitness identification reform. The next one, which Chris worked on, was on recording interrogations— something that many prosecutors, certainly not all, but many are interested in because it helps them to prove their own cases.

With this campaign, we used a tag-team approach at the hearing. In Colorado I testified as to the nuts and bolts of the issue of false confessions. Chris then helped me to bring that story to life for lawmakers.

To be honest, without people like Chris or advocates like Jennifer Thompson, I just don’t know where we would be in getting legislation passed. It’s hard for people to connect to facts and figures. But when they look in to the face of someone who has been through it, and they hear the stories of people like Chris who was threatened with the death penalty and almost lost his life—it’s hard for people to not be affected by that, to not be changed.

Innocence Project (IP): Chris, had you been involved in any Innocence Project related policy work prior to working with Amshula in Colorado?

Chris: Yes, I’ve done policy work for almost 20 years now. Colorado was just one of several states where I’ve worked. I’ve been a political junkie since college. I love political science. So for that reason, I love to be involved. But, the biggest reason is that it’s very satisfying.

I started partnering with the Innocence Project on policy work about two years after I was released. The Innocence Project had started to do some work in Texas, and asked a number of exonerees— including me—to talk to legislators about various bills that they were working on.

After that I went on to do a lot policy work trying to ramp up their compensation law in Wisconsin. I went to law school there, and it was the Wisconsin Innocence Project that actually helped me get relief.

The work I did in Colorado, though—to get recording of interrogations passed— was especially satisfying. Ever since I was exonerated, in 2001, getting that law passed has been my goal. In my case, if the interrogation had been recorded, specifically mandated, then maybe I wouldn’t have been wrongfully convicted.

If we can get recording of interrogation laws in place, and it can prevent even just one kid from being wrongfully convicted and preserve their freedom—their life— to me, it makes the work so worth it. No one should have to spend one day, much less years in jail or prison for a crime they haven’t committed. For me, preventing that injustice is very satisfying.

For my part, working in Colorado or anywhere I go, the Innocence Project does a really good job of preparing me. They help me to know the audience—who the legislators are that I’m addressing. Based on my knowledge of them, I know which aspects of my story or the bill to emphasize. I try to look for the best political angle.

Amshula: I think that’s exactly right. Chris and many of the clients that I’ve worked with are already political. So, they know how to emphasize certain aspects of their story. And it works. In Chris’ case, being able to talk about how a specific reform could have changed the outcome of his case—it made all the difference.

IP: What are some of the challenges to doing this work?

Amshula: The legislative session is so hectic. It can be chaotic.

Chris: I’m immune to that. I’ve been doing this work for a long time and I’m used to that environment. I think that as long as I have the attention of even two or three people, I’m fine. It doesn’t bother me. The important thing, to me, is that someone is listening to us. And before the Innocence Project, who was listening to us? No one.

For us exonerees, we will run through a hoop of fire for the Innocence Project. Our freedom— we owe it to the project and the Network. Just to be able to testify makes us feel useful.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.