Hit in DNA Database Proves Leonard Mack’s Innocence After 47 Years of Wrongful Conviction

Unreliable witness identifications along with racial bias and tunnel vision led to Mr. Mack’s wrongful conviction, the longest to be vacated based on DNA evidence.

Breaking News 09.05.23 By Innocence Staff

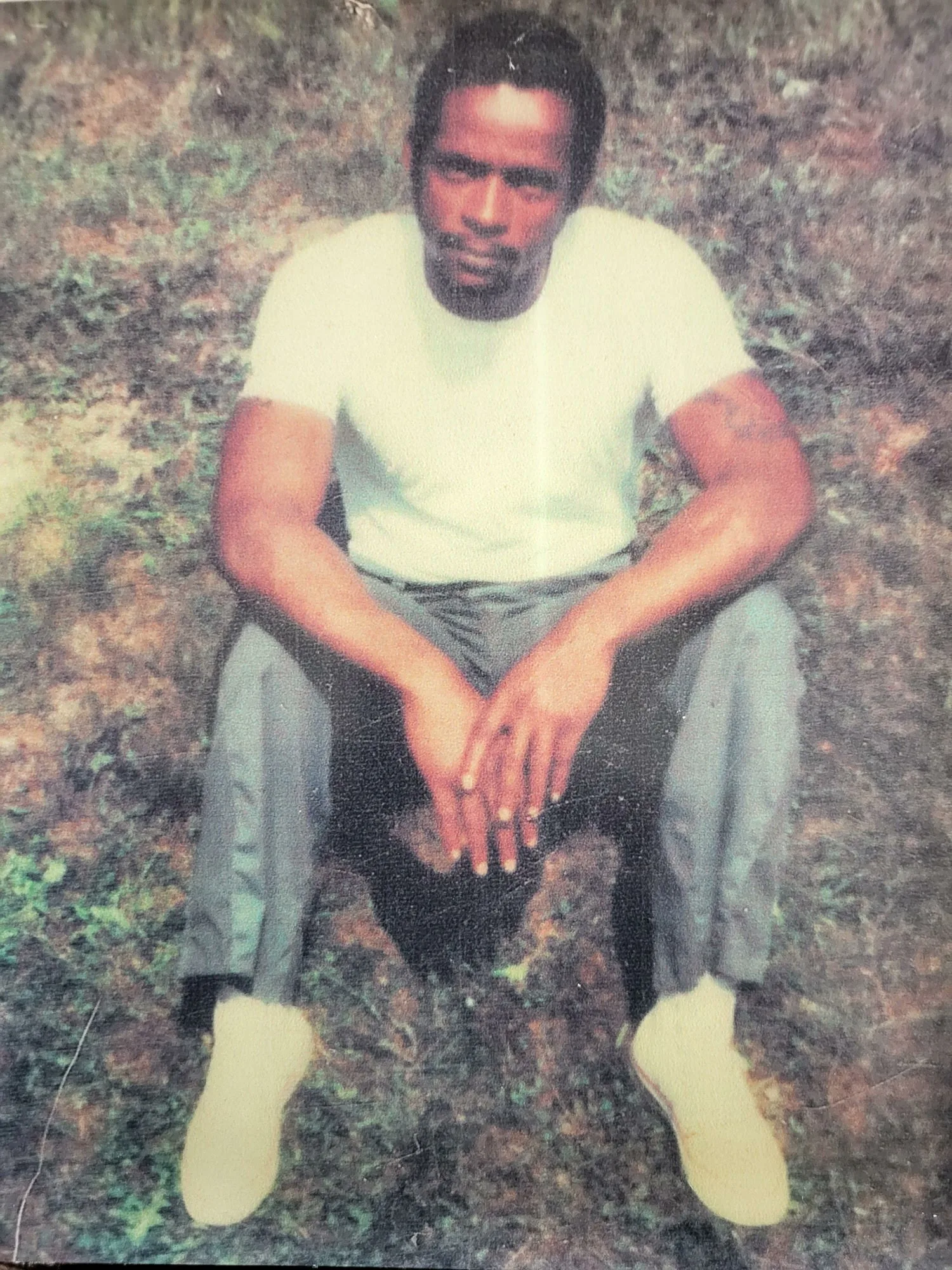

Leonard Mack at Elmira Correctional Facility in 1978.

(September 5, 2023 — White Plains, NY) Leonard Mack was exonerated today nearly five decades after he was wrongfully convicted of rape and two counts of criminal possession of a weapon in March 1976. New DNA testing of crime scene evidence found in a post-conviction investigation by the Innocence Project and the Westchester County District Attorney’s Conviction Review Unit proved Mr. Mack did not commit the crime. Mr. Mack’s wrongful conviction is the longest to be overturned based on new DNA evidence known to the Innocence Project. The DNA profile developed from the evidence was uploaded to the state and local DNA database and yielded a hit. The actual assailant identified by this search has since confessed to the crime.

This case contains virtually every common contributing factor in wrongful convictions. Eyewitness misidentification, the leading cause of wrongful convictions, played a central role, in addition to misleading forensic testimony presented by the State’s forensic analyst at trial, racial bias, and tunnel vision. Despite alibi witnesses and serological evidence from the victim’s underwear that excluded Mr. Mack in 1976, he spent seven-and-a-half years in prison and has since lived with this wrongful conviction for 41 years.

“Today, indisputable DNA evidence proves that Leonard Mack is innocent. Nearly five decades later, he finally has some measure of justice,” said Mary-Kathryn Smith, one of Mr. Mack’s Innocence Project attorneys. “Mr. Mack’s resilience and strength is why this day has finally come. We want to thank the Westchester County District Attorney and its Conviction Review Unit for their cooperation and commitment to search for the truth.”

“I want to first thank God for this day. Next, I want to thank the Innocence Project. Today has been a long time coming. I lost seven-and-a-half years of my life in prison for a crime I did not commit and I have lived with this injustice hanging over my head for almost 50 years. It changed the course of my life — everything from where I lived to my relationship with my family. I never lost hope that one day that I would be proven innocent. Now the truth has come to light and I can finally breathe. I am finally free.”

Westchester County District Attorney Miriam E. Rocah said, “Today we’re asking the courts to find Leonard Mack actually innocent for a rape he never committed; for which he unjustly served more than seven years in prison. We were able to prove Mr. Mack’s innocence, in large part, due to our independent Conviction Review Unit’s commitment and Mr. Mack’s unwavering strength fighting to clear his name for almost 50 years. This exoneration and the new DNA evidence confirm that wrongful convictions are not only harmful to the wrongly convicted but also make us all less safe.”

Leonard Mack Exonerated on his 72nd Birthday

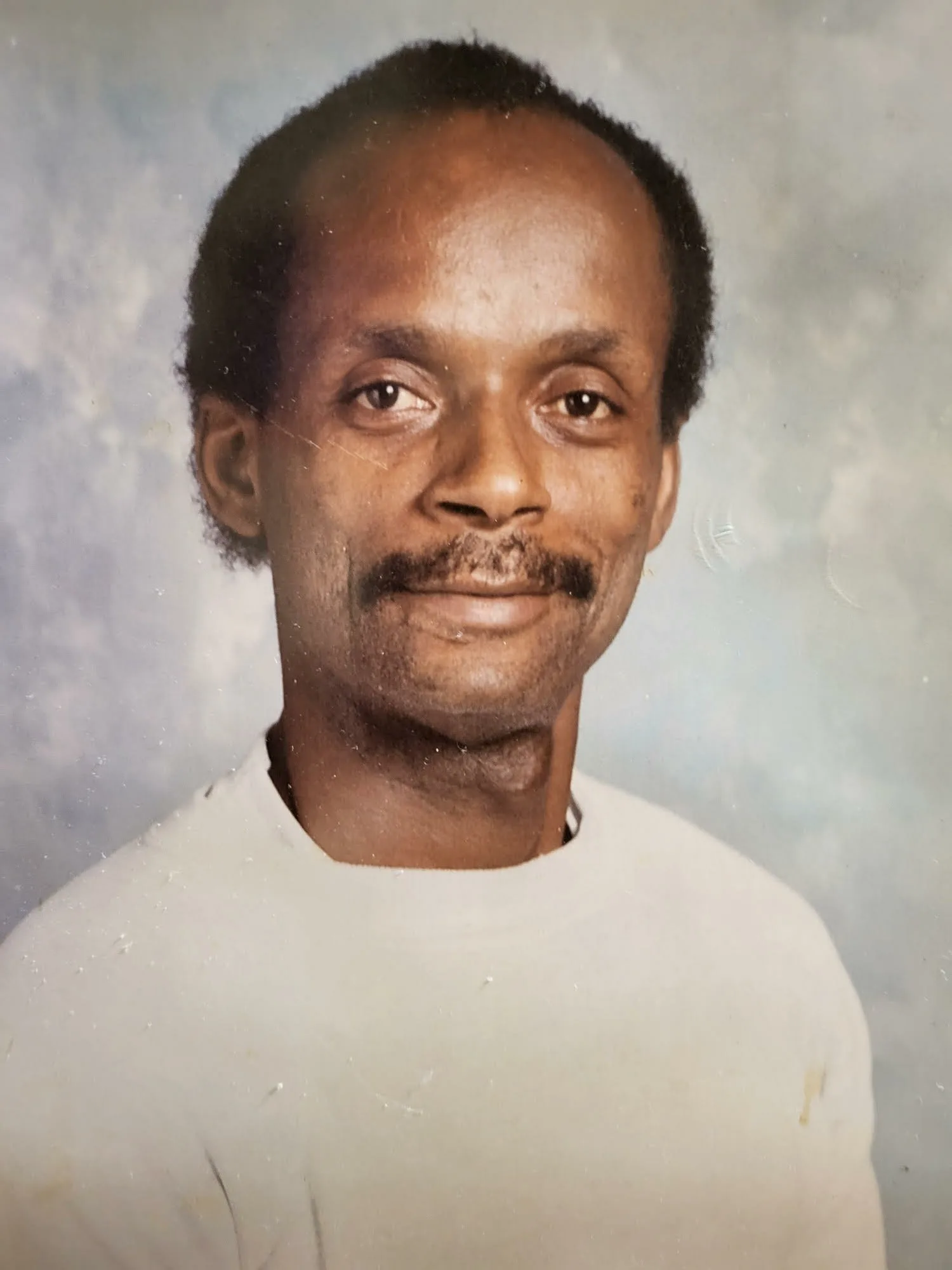

Leonard Mack in 1993.

Multiple Eyewitness Misidentifications

On May 22, 1975 at 3:00 p.m., two 12th-grade students from Woodland High School were walking home from school near a wooded area in Greenburgh, NY, when a man approached them and held them at gunpoint. He told them not to scream or he would kill them, and proceeded to use their belt and shreds of jacket to blindfold, gag, and restrain both girls’ wrists and ankles. He then raped one of the girls twice and threatened them again as he left the scene. The girl who was not raped broke free and ran to a nearby school where a teacher called the police. The second victim, who was raped, freed herself and ran home, where her sister also called the police, before being taken to the hospital where a rape kit was collected.

The Greenburgh Police Department issued a dispatch for officers to be on the lookout for a Black male suspect in his early 20s, close cropped hair, clean shaven with a medium build, wearing black pants, a tan jacket, a black hat with a white brim, and a gold earring in his left ear, and carrying a .22 or .32 caliber handgun.

Roughly two-and-a-half hours later, Officer James Fleming pulled over Mr. Mack, who was wearing a black fedora hat and had a gold earring in his left ear, on Harney Road. Officer Fleming told Mr. Mack he matched the profile of a rape suspect, although his clothing did not match the description the teenagers gave to police. Mr. Mack denied any involvement in the crime and explained he was with his girlfriend at the time of the attack, which she corroborated. Officer Fleming searched Mr. Mack’s vehicle and, finding a .22 revolver in the trunk, placed him under arrest. Both girls were then asked to identify him in a series of highly suggestive and problematic identification procedures.

One of the victims was brought to Harney Road, where Mr. Mack was in handcuffs and surrounded by Officer Fleming and six police cars. At first, unsure, the girl asked police to reposition him, at which point she identified Mr. Mack as the assailant. She was then taken to Greenburgh Police Station and presented with a photo array containing seven photos of Black men, including that of Mr. Mack. His was the only photo showing his face and clothing, along with a distinctive May 1975 calendar hanging in the background, clearly differentiating it from others. The girl selected Mr. Mack’s photograph.

In a third identification attempt, the same girl was taken to the Parkway police station later that evening where police conducted a show-up — when witnesses are presented with only one suspect for identification — through a one-way mirror. According to Officer Fleming’s testimony, it was not “feasible” to put together a line-up of Black males in the “basically white” Greenburgh area. Not surprisingly, the girl identified Mr. Mack, later describing him as the person she was supposed to identify. The girl later mentioned that Mr. Mack was wearing the wrong clothes, upon which police showed her clothing options allowing her to pick out the right clothes for Mr. Mack to wear. She again identified him as her assailant.

The same suggestive photo array was later shown to the other victim after she left the hospital and was taken to the Greenburgh police station. This girl was legally blind and had stated that she was unable to tell the gender of a person unless they were within 10 feet of her and could not see the color of someone’s clothing unless they were within five feet. She told detectives she recognized one man’s shirt, referring to Mr. Mack’s photo, but could not be sure of her identification.

She was then taken to the Parkway police headquarters, where she viewed Mr. Mack through a one-way mirror with the other victim, who told her, “That’s him.” The girl could not identify Mr. Mack, saying only, “It could be, I think so.” She said that Mr. Mack was the same “size, shape, and color” as the man who had attacked her. Given the limitations of her identification, she asked if she could hear Mr. Mack’s voice. At that point, police had Mr. Mack repeat what the attacker said to the girls through a door: “Don’t scream, don’t turn around or I’ll kill you.” Based on this, the girl identified Mr. Mack as the assailant.

Eyewitness misidentification, as in this case, is the leading contributing factor of wrongful convictions and has contributed to 64% of the Innocence Project’s 245 exonerations and releases. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, intentionally suggestive witness identifications occur twice as frequently in the cases of Black and Latinx exonerees as they do in the cases of white exonerees. In 2017, New York passed a law adopting standards and best practices, advocated for by the Innocence Project, around eyewitness identification procedures that law enforcement agencies were required to implement.

Flawed Forensic Testimony at Trial

At trial, the State’s case rested almost entirely on the victims’ identification of Mr. Mack. In addition to three alibi witnesses who accounted for Mr. Mack’s whereabouts the afternoon of the crime, the defense presented testimony from Dr. Alexander Wiener from the Office of Chief Medical Examiner in New York City. Dr. Weiner testified that the State had confirmed there was sperm on the victim’s vaginal swab and that biological material found on her underwear, which had tested positive for acid phosphatase, a presumptive test for semen, had excluded Mr. Mack through serological testing. The basis for this exclusion was that the biological evidence indicated that the assailant was blood type A, which is not Mr. Mack’s blood type.

The State, which did not include any of the serology evidence in its case, presented testimony from an analyst from the forensic science lab for Westchester County in its rebuttal case. The analyst attempted to cast doubt on Dr. Wiener’s testimony by incorrectly suggesting that the victim may have been the source of the biological evidence. On March 29, 1976, Mr. Mack was found guilty of all three charges.

Missteps: Racial Bias and Tunnel Vision

Satisfied that they had their suspect, a Black male wearing a black hat and a gold earring in a predominantly white neighborhood, the State failed to search for the true assailant. Because of information based on little more than his race, Mr. Mack “fit the description” and his fate was sealed. Despite all the contradictory factors — Mr. Mack’s clothing not matching the original description, the unreliable identifications, and the exculpatory serology evidence — police made no efforts to investigate further. Such tunnel vision, fixing on a single theory or suspect, is a known consequence of implicit racial bias that contributes to the deep racial disparities evident in wrongful convictions. While just 13.6% of the American population identify as Black, they account for 53% of the 3,200 exonerations listed in the National Registry of Exonerations according to its 2022 report, Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States. Based on exonerations, innocent Black Americans are seven times more likely than white Americans to be falsely convicted of serious crimes. Similarly, of the 245 people the Innocence Project has helped free or exonerate, 58% are Black.

DNA Identifies the True Perpetrator

In November 2022, the Innocence Project contacted the Westchester County District Attorney’s Conviction Review Unit seeking its assistance and collaboration in finding and testing biological evidence in this case. Most of the crime scene evidence no longer existed, but the Conviction Review Unit did find the victim’s underwear cuttings that tested positive for semen along with Mr. Mack’s underwear. Using modern DNA testing methods, the Westchester County forensic lab excluded Mr. Mack as the source of the DNA on the victim’s underwear. The DNA evidence was then uploaded to the state and local DNA database. The search yielded a hit to to an individual who was convicted of a burglary and rape in Queens that occurred weeks after this crime. He also had a 2004 conviction for burglary and sexual assault of a woman in Westchester County.

Mr. Mack is a Vietnam War veteran and has lived with his wife in South Carolina for nearly 21 years.

Mr. Mack is represented by Susan Friedman, a senior staff attorney at the Innocence Project, and Post-conviction Litigation Fellow Mary-Kathryn Smith.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.