10 Year Anniversary of the Landmark Report on Forensic Evidence

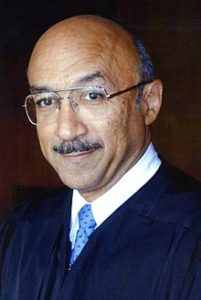

02.21.19 By Honorable Harry T Edwards

Hon. Harry Thomas Edwards is currently a Senior United States Circuit Judge, chief judge emeritus of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in Washington, D.C. and professor at the New York University School of Law. In 2006, the United States National Research Council at the National Academy of Sciences appointed Judge Edwards to serve as co-chair of the Committee on Identifying the Needs of the Forensic Science Community. Notably, Judge Edwards is an acclaimed author and scholar of legal education, judicial decision-making and racial equality and inequality in America. Below is a statement he drafted about the importance of the 2009 National Academy of Sciences report, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward.”

Ten years ago, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report entitled, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward.” The report reached the extraordinary conclusion that, “[w]ith the exception of nuclear DNA analysis, . . . no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source.” The report found that “much forensic evidence – including, for example, bite marks . . . – is introduced in criminal trials without any meaningful scientific validation, determination of error rates, or reliability testing to explain the limits of the discipline.” The report not only exposed the paucity of scientific research to support forensic methods, it also detailed some dubious practices in crime laboratories, the absence of rigorous certification requirements and robust performance standards for practitioners, and the failure of forensic experts to use standard terminology in reporting on and testifying about the results of forensic investigations. Yet, as the report noted, despite the “serious issues regarding the capacity and quality” of forensic practice, “the courts continue[d] to rely on forensic evidence without fully understanding and addressing the limitations of different forensic science disciplines.”

A serious problem in the forensic science community was that many practitioners concededly did not know what they did not know: they often believed their methods were reliable and their conclusions were accurate with little or no scientific foundation for their beliefs. As a consequence, judges and jurors were misled about the efficacy of forensic evidence, which too often resulted in wrongful convictions. And yet, despite the alarming lack of scientific support for forensic methods, some prosecutors and forensic practitioners criticized the report when it was issued because it challenged established practices. When I explained the situation to my eight year-old grandson, he asked me, “Grandpa, does something bad become good just because it has been followed for a long time?” The answer is obvious.

Related: Ten Years Later: The Lasting Impact of the 2009 NAS Report

In the last ten years, the report has consistently and remarkably drawn attention to the problems associated with forensic science evidence. There have been countless conferences, television programs, news reports, and scholarly articles that have thoughtfully addressed the problems that plague the forensic science community. We have also seen some notable developments in the forensic science community. Several professional associations, such as the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, have endorsed the report. In 2015, the FBI conducted a review of its testimony relying on microscopic hair analysis and publicly admitted that, in over ninety percent of cases examined, its testimony contained errors. The Texas Forensic Science Commission, a body convened specifically to review the validity of questionable fields of forensics, recommended a moratorium on the use of bite mark analysis in court. And some former proponents of bite mark evidence have recanted on their claims regarding the viability of this forensic method. In 2016, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology issued an exhaustive and compelling study debunking several forensic methods and calling for better scientific research. A number of crime laboratories have come under investigation after shoddy, suspect, or fraudulent results were uncovered. The National Institute of Justice has maintained its support of research in forensic science for criminal justice. Although judges have been slow to exclude forensic evidence outright, more judges are now imposing restrictions on forensic examiners’ testimony to prevent overstatements about the strength and meaning of forensic evidence. And there have been a number of highly-publicized exonerations of people who were wrongfully convicted on the basis of faulty forensic evidence. In all of these situations, “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward” is invariably cited.

This is progress. Nevertheless, to continue on the “Path Forward,” much remains to be done. For example, in the report, the Committee recommended the establishment of “a strong, independent, strategic, coherent, and well-funded federal program [with a culture that is strongly rooted in science] to support and oversee the forensic science disciplines.” That has not happened. In 2013, the Department of Justice established a National Commission on Forensic Science, in partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, purportedly to enhance the practice and improve the reliability of forensic science. However, over the objection of a number of Commission members, DOJ disbanded NCFS in 2017. In 2014, NIST established the Organization of Scientific Area Committees to coordinate the development of standards and guidelines to improve the quality and consistency of work in the forensic science community. But NIST does not see its role as ensuring that a scientific basis exists for forensic methods. And NIST is not a standard-making agency, nor is it a regulator. As a result of the absence of a national, independent agency to oversee forensic research and practices, there is still too much forensic evidence admitted supporting criminal prosecutions that falls well short of the types of requirements that we set in our regulations of food, cosmetics, and even television programs.

Perhaps most critically, we still do not know what we do not know. We need better scientific studies and standards to shape the work of forensic practitioners and regulate the admission of forensic evidence. This means that more top scientists must engage in research on forensic methods and appear in court to explain the evidence. This will allow judges to better understand forensic evidence and to more clearly and accurately instruct jurors on the limits of the evidence. Faulty forensic evidence has no place in our system of justice. It is gratifying to know that the recommendations in “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward” set forth a viable blueprint for continued reform in the years ahead.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

May 14, 2019 at 8:52 am

March 1, 2019 at 2:30 am

I as a former Judge and defense attorney would have to know what other evidence was admitted. I hope he exercised his right to appeal. Good luck.

Add firearm analysis to the list. Like hair and fingerprints, until standards are developed, it should only be important as exculpatory, not inculpatory. That is, it should only server as evidence of exclusion. Just as bad, footprint analysis as now practiced.