Wrongful Convictions Revealed the Dangers of Trusting Unvalidated Science. Are We About to Repeat the Same Mistakes With AI?

Emerging technologies like AI-based surveillance systems lack independent verification, empirical testing, and error rate data, leading to wrongful arrests and potentially wrongful convictions.

10.03.24 By Katherine Jeng

In 2016, Silvon Simmons was shot three times after Police Officer Joseph Ferrigno mistakenly believed that the car he was in belonged to someone involved in a criminal investigation. Officer Ferrigno told detectives that Mr. Simmons had shot at him, resulting in charges of attempted aggravated murder, attempted aggravated assault of a police officer, and two counts of criminal possession of a weapon being leveled at Mr. Simmons.

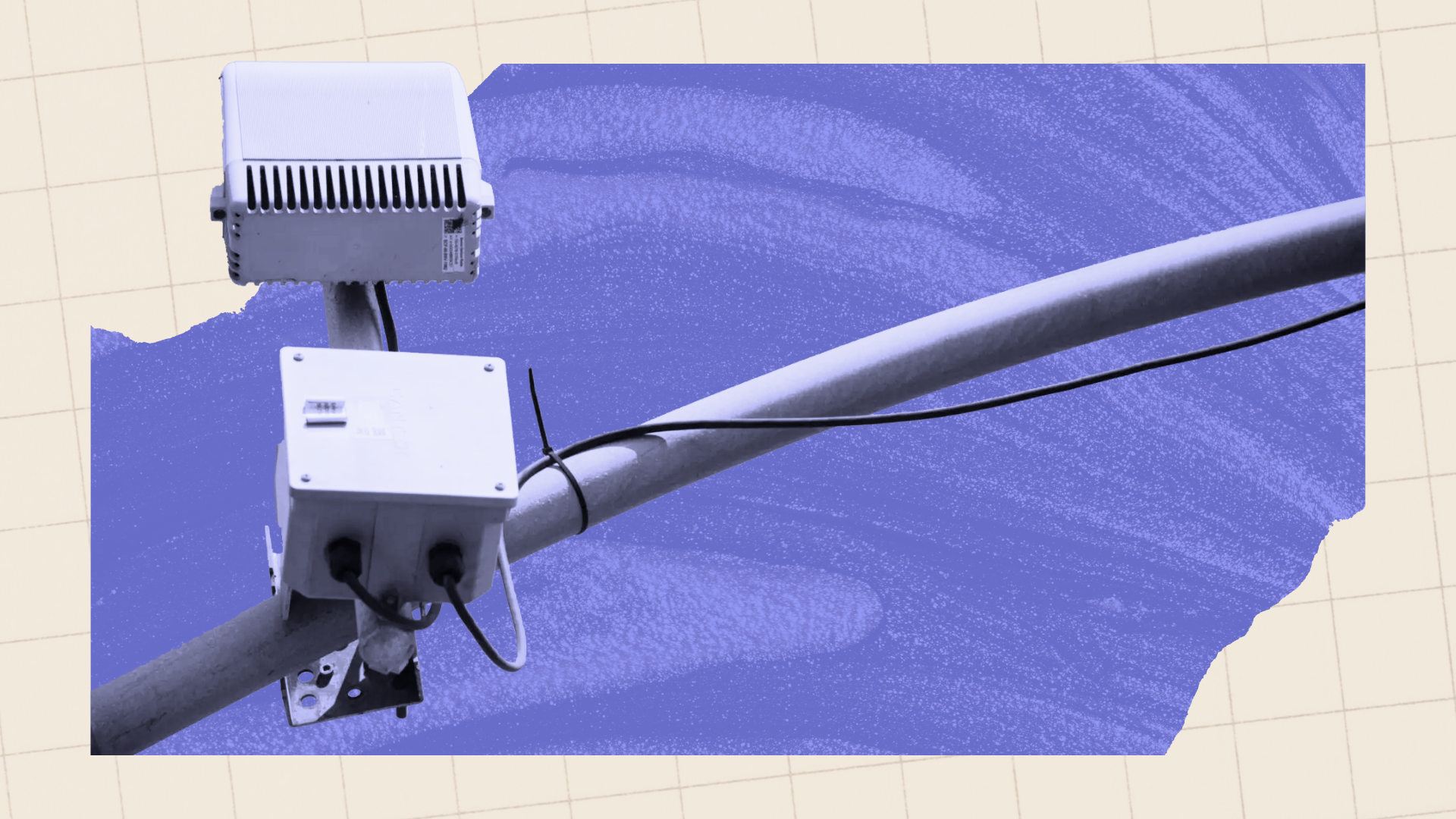

At trial, prosecutors turned to a piece of contested forensic evidence — an audio spool captured by ShotSpotter, an artificial intelligence-powered gunshot detection system — to argue Mr. Simmons had exchanged gunfire with Mr. Ferrigno.

A ShotSpotter engineer testified that the system identified five shots, suggesting that two had come from Mr. Simmons and contradicting the company’s earlier conclusion that the sounds detected by its sensors that night were from a helicopter, not gunfire. Mr. Simmons consistently denied firing any shots or even owning a gun.

Although jurors voted to not convict Mr. Simmons on most of the charges, they voted to convict him on a gun possession charge. The trial judge, however, tossed the conviction, stating that the ShotSpotter evidence was not reliable enough to sustain any charges.

While Mr. Simmons narrowly escaped a wrongful conviction, the very introduction of ShotSpotter evidence in his case reflects a disturbing readiness among some system actors, especially prosecutors, to accept AI-based evidence at face value. This eager acceptance mirrors the same flawed embrace of misapplied forensic science, which has contributed to numerous wrongful convictions.

“Half of the Innocence Project’s victories to date involved wrongful convictions based on flawed forensic science,” Vanessa Meterko, Innocence Project’s research manager, said. “We don’t want to see this same pattern with untested or biased AI in the years to come.”

The use of unreliable forensic science has been identified as a contributing factor in nearly 30% of all 3,500+ exonerations nationwide. Take bite mark analysis, for example. The practice was widely used in criminal trials in the 1970s and 1980s but is poorly validated, does not adhere to scientific standards, lacks established standards for analysis and known error rates, and relies on presumptive tests. It has since been discredited as unreliable and inadmissible in criminal trials due to its shortcomings. Still, there have been at least 24 known wrongful convictions based on this unvalidated science in the modern era.

There has been some progress. Amid a growing number of documented wrongful convictions and advances in forensic science disciplines, some states have begun to implement “change in science” statutes to allow innocent people to bring their cases back into court.

At the same time, the courts’ approach to scientific evidence has evolved. The 1923 Frye v. United States decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, for instance, introduced the “general acceptance” standard for admissibility, meaning that the scientific technique at the center of a case needed to have enough recognition, reliability, and relevance in the scientific community to be “generally accepted” as evidence in court. Some state courts still apply this standard today.

Federal courts and many other state courts, on the other hand, abide by the Supreme Court’s 1993 ruling in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., which shifted the focus to evaluating the relevance and reliability of expert testimony to determine whether it is admissible in court.

In applying the Daubert standard, a court considers five factors to determine whether the expert’s methodology is valid:

- Whether the technique or theory in question can be, and has been, tested;

- Whether it has been subjected to publication and peer review;

- Its known or potential error rate;

- The existence and maintenance of standards controlling its operation; and

- Whether it has attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community.

Under the Daubert and Frye standards, much AI technology, as currently deployed, doesn’t meet the standard for admissibility. ShotSpotter, for example, is known to alert for non-gunfire sounds and often sends police to locations where they find no evidence that gunfire even occurred. It can also “significantly” mislocate incidents by as much as one mile. It, therefore, should not be admissible in court.

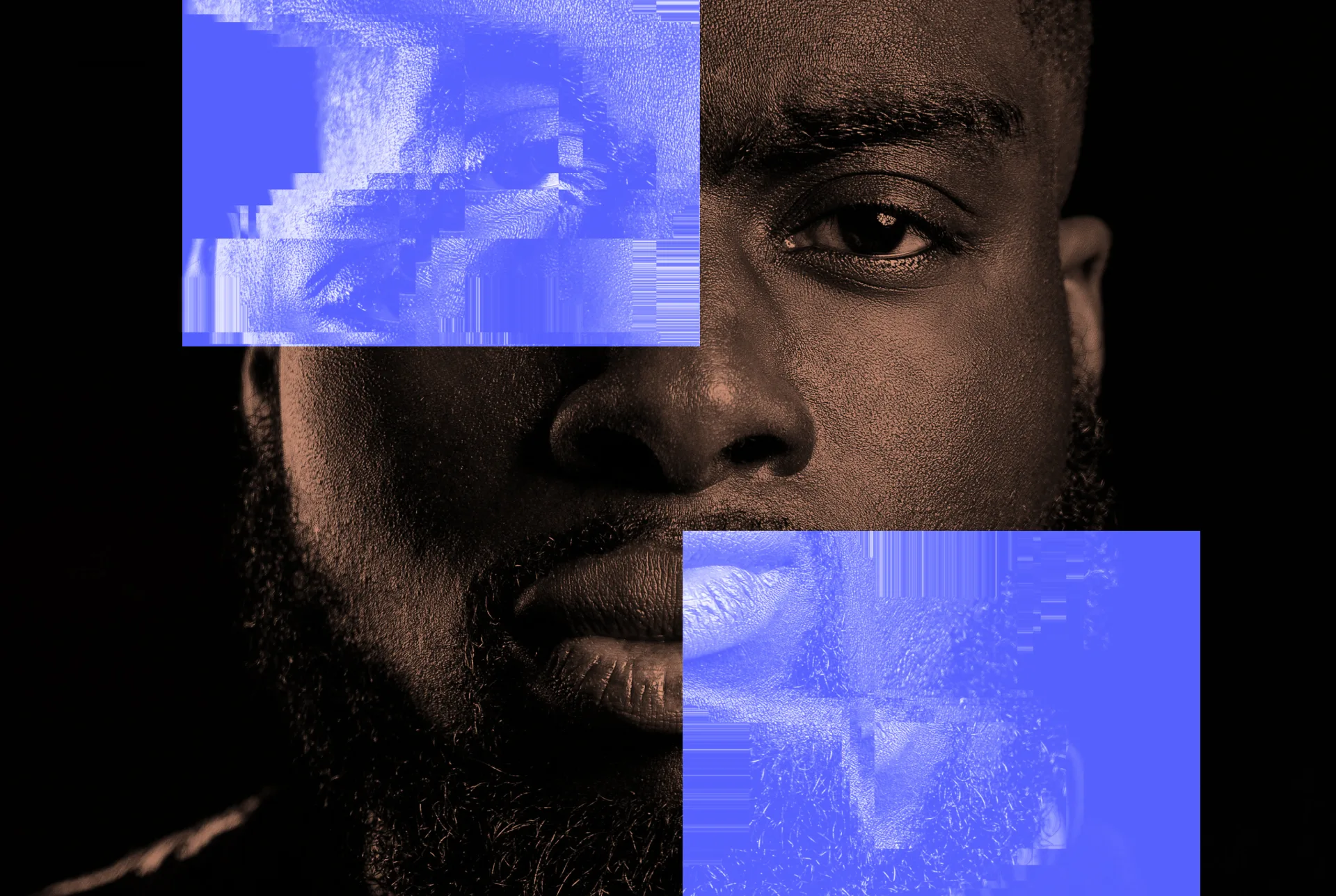

Similarly, facial recognition technology’s susceptibility to subjective human decisions raises serious concerns about the technology’s admissibility in court. Such decisions, which empirical testing doesn’t account for, can compromise the technology’s accuracy and reliability. Research has already shown, for instance, that many facial recognition algorithms are less accurate for women and people of color, because they were developed using photo databases that disproportionately include white men.

Worse, some courts aren’t applying the Frye or Daubert standard adequately — or at all — to these novel technologies.

“While science and technology have incredible potential to reveal truth and improve our world, we shouldn’t adopt these things without a critical assessment of not only their validity and reliability, but also their ethical, legal, and social implications,” Ms. Meterko said.

If we are to prevent a repeat of the injustices we’ve seen in the past from the use of flawed and untested forensic science, we must tighten up the system. Too many investigative and surveillance technologies remain unregulated in the United States.

“Unvetted technology risks compounding human error and cognitive bias, even as it can mask those errors with a veneer of technological sophistication,” said Mitha Nandagopalan, a staff attorney at the Innocence Project. “And human decisions can end up being a rubber stamp for flawed technology.”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.