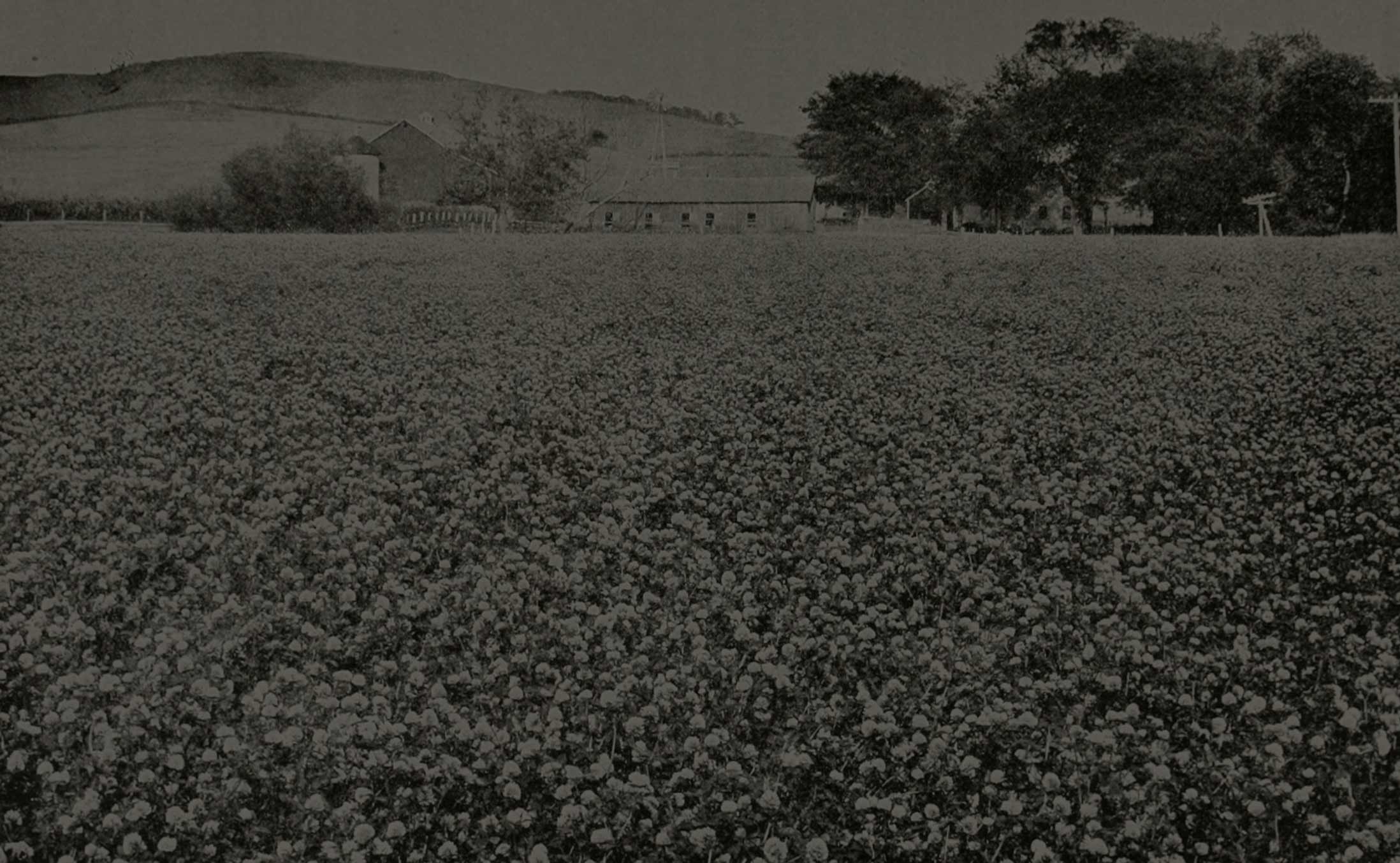

For nearly a century, Black children could be bought to serve as laborers for white plantation owners throughout the South. (Image: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-D428-850)

Special Feature 05.29.20 By Innocence Staff

Courtesy of Gloria Williams.

In her memoir Men We Reaped, Mississippi-born writer Jesmyn Ward recalls a Christmas Eve when she was 9-years-old and woke up in tears after a nightmare. In the dream, all of her uncles and father had been arrested and sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary — an infamous prison in the Mississippi Delta, often referred to as Parchman Farm.

“When I thought about prison, that’s the prison that came to mind,” Ward said in a 2018 interview with PBS News Hour. “I didn’t know much about it, but I knew it was a place I never wanted to end up. And the danger that I would end up there was a real thing, for me and for people that I know and loved.”

The danger became a reality for Levon Brooks in 1990 when he was arrested and wrongfully convicted in Noxubee County, Mississippi. And Ward’s nightmare, that she would lose her uncle to Parchman prison, became reality for Brooks’ 19-year-old niece, Gloria Williams. Brooks, her favorite uncle, was wrongly accused of raping and murdering a 3-year-old girl from their neighborhood.

“We knew he was innocent,” Gloria says, “that he couldn’t have done what they said.” Brooks spent 15 years at Parchman before being exonerated.

“They just wanted anybody,” Brooks’ father, Richard Brooks, said in “The Innocence Files,” a documentary series on Netflix. His words encapsulate what it means to be poor and black in America — an especially common reality in Mississippi, the poorest and blackest state in the country. Today, Black Mississippians account for 70% of Parchman’s incarcerated population, while making up 37% of the state’s population.

“By the numbers, by all the official records, here at the confluence of history, of racism, of poverty, and economic power, this is what our lives are worth: Nothing.”

“By the numbers, by all the official records, here at the confluence of history, of racism, of poverty, and economic power, this is what our lives are worth: Nothing.”

Jesmyn Ward Author of Men We Reaped

Parchman’s history is rooted in Black suffering.

After the Civil War, the South’s economy, government, and infrastructure were left in compete shambles. Desperate to restore the previous economic and social order and to control the freedom of newly emancipated African Americans, Southern states adopted criminal statutes, collectively known as “Black Codes,” that sought to reproduce the conditions of slavery. These laws are also commonly known as Jim Crow laws.

“The plantation owners, as best they could, wanted Blacks to return to the same place as they had been as slaves,” according to historian David Oshinsky, author of Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice.

In addition to denying Black people the right to vote, serve on juries, and testify against white people, African Americans could be arrested en masse for minor “offenses” such as vagrancy, mischief, loitering, breaking curfew, insulting gestures, cruel treatment to animals, keeping firearms, cohabiting with white people, and not carrying proof of employment — actions which were not considered criminal when done by white people.

In Mississippi, Texas, and other states, legislatures passed “Pig Laws,” which labeled the stealing of a farm animal — or any property valued at more than $10 — “grand larceny,” punishable by five years in prison. Such laws were enforced almost exclusively against Black people, reinforcing the man-made association between Blackness and criminality. “A single instance of punishment of whites under these acts has never occurred,” declared a Tennessee Black convention, “and is not expected.”

While the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, it carved out a loophole that allowed for the exploitation of incarcerated people, who were then and now, disproportionately Black.

The amendment abolished slavery and involuntary, “except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Prisoners — men, women, and hundreds of children as young as 6 or 7 — were then leased to private farmers and business owners who’d previously depended on cheap labor supplied by slaves. By 1880 “at least 1 convict in 4 was an adolescent or a child — a percentage that did not diminish over time,” according to Oshinsky.

For nearly a century, Black children could be bought to serve as laborers for white plantation owners throughout the South. (Image: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-D428-850)

States profited substantially from the Black Codes and prisoner leasing system. The number of state prisoners in Mississippi rose from 272 in 1874, the year the “Pig Law” was passed, to 1,072 by 1877.

“They needed a workforce,” Oshinsky wrote in Worse Than Slavery. “The best workforce and the cheapest workforce they could get were convicts who were being arrested for largely minor offenses and then leased out for $9 a month.”

The system was synonymous with violence and brutality, a murderous industry considered “slavery by another name.” In 1882, for instance, nearly 1 in 6 Black prisoners died because, unlike under chattel slavery, lessees had little incentive to safeguard the lives of prisoners. “Different from chattel slavery, ‘It is to be supposed that sub-lessees [take] convicts for the purpose of making money out of them,’ wrote a prison doctor, ‘so naturally, the less food and clothing used and the more labor derived from their bodies, the more money in the pockets of the sub-lessee’,” Oshinsky wrote.

Working prisoners to literal death was so commonplace that “not a single leased convict ever lived long enough to serve a sentence of ten years or more,” he wrote.

Due to shifts in the political and economic landscapes, prisoner leasing faded in the early 20th century, but in its place rose Parchman Farm in Mississippi, Angola prison in Louisiana, and hundreds of other county camps — prisons that used racial oppression to create a supply of forced labor.

The original superintendent’s residence at Mississippi State Penitentiary (Wikimedia Commons).

In 1901, the state of Mississippi began purchasing land in the heart of the Mississippi Delta — home to some of the richest land and most successful cotton plantations in the United States, including Parchman plantation, named after the family that previously owned the land. Months after its purchase, prisoners were taken to Parchman and ordered to prepare the land for farming.

In Worse Than Slavery, Oshinsky chronicles the history of Parchman Farm, which he describes as “the quintessential penal farm, the closest thing to slavery that survived the civil war.” People incarcerated there labored sunup to sundown, sometimes 15 hours a day in 100 degrees Fahrenheit, on Parchman’s 20,000-acre plantation, planting, picking cotton, and plowing fields under the control of armed guards.

“Convicts dropped from exhaustion, pneumonia, malaria, frostbite, consumption, sunstroke, dysentery, gunshot wounds, and ‘shackle poisoning’ (the constant rubbing of chains and leg irons against bare flesh),” Oshinsky wrote.

For the state of Mississippi, Parchman was “a giant money machine: profitable, self-sufficient and secure,” Oshinsky observed. By the end of its second year of operation, Parchman earned $185,000 for the state of Mississippi, the modern-day equivalent of roughly $5 million. For those imprisoned at Parchman — 90% of whom were Black, it was legalized torture. Inmates were whipped into submission by a “leather strap, three-feet-long and six-inches-wide, known as ‘Black Annie,’ which hung from the driver’s belt.” According to Oshinsky:

At Parchman, formal punishment meant a whipping in front of the men. It was done by the sergeant, with the victim stripped to the waist and spread-eagled on the floor. What convicts most remembered were the sounds of Black Annie: the ‘whistlin’ air, the crack on bare flesh, the convict’s painful grunt…When asked to defend Black Annie, Parchman officials did so with pride. The lash was effective punishment, they insisted, and it did not keep men from the fields. ‘You spank a fellow right,’ claimed a superintendent, ‘and he’ll be able to work on.’ Most of all, Black Annie seemed the perfect instrument of discipline in a prison populated by the wayward children of former slaves. There simply was no better way ‘of punishing [this] class of criminals,’ said Dr. A.M. M’Callum, Parchman’s first physician, ‘and keeping them at the labor required of them.’

Parchman also relied on the “trusty system.” Incarcerated people known as “trusty-shooters,” some of them convicted of the most violent crimes, were selected to intimidate and watch over others who were incarcerated. Armed with rifles, they were expected to use brutal force to maintain order. The horrors of Parchman Farm — referred to as “destination doom” in William Faulkner’s novel The Mansion — have been documented in works of fiction and nonfiction, including novels, plays, and blues songs, such as Bukka White’s “Parchman Farm Bluess”:

Oh listen you men, I don’t mean no harm (2×)

If you wanna do good, you better stay off ol’ Parchman farm

We got to work in the mornin’, just at dawn of day (2×)

Just at the settin’ of the sun, that’s when the work is done

“There were two reasons for Parchman. One was money-making and the other was racial control. They went hand in hand.”

“There were two reasons for Parchman. One was money-making and the other was racial control. They went hand in hand.”

David Oshinsky Author of Worse Than Slavery

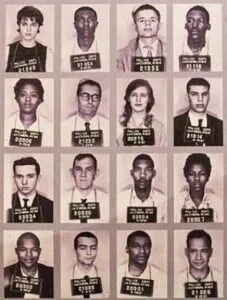

Mug shots of some of the more than 300 Freedom Riders who were arrested in Mississippi during the summer of 1961.

In the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders, including Stokely Carmichael and Joan Trumpauer, were sent to Parchman for challenging the policy of segregation on public buses. While at the prison, they were kept in horrid conditions, isolated in the supermax unit on death row, and often served inedible food. Their treatment brought national attention to the prison’s dangerous, inhumane conditions. Despite criticism — and Supreme Court rulings declaring segregated interstate buses unconstitutional — Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett defended his treatment of the activists, reportedly telling Minnesota delegates, “When people come here to willfully violate the laws, you can’t expect them to be treated like they were at a tea party.”

In 1971, Parchman inmates filed a class action la suit (Gates v. Collier) against the superintendent of Parchman Farm, members of the Mississippi Penitentiary Board, and the governor, arguing that “deplorable conditions and practices” violated the prisoners’ civil rights. When federal judge William C. Keady inspected the facility he found an “institution in shambles, marked by violence and neglect,” wrote Oshinsky. “The camps were laced with open ditches, holding raw sewage and medical waste. Rats scurried along the floors. Electrical wiring was frayed and exposed; broken windowpanes were stuffed with rags to keep out the cold … he saw filthy bathrooms, rotting mattresses, polluted water supplies and kitchens overrun with insects, rodents and the stench of decay.”

After several visits, Keady declared that Parchman was “an affront to modern standards of decency” and the living conditions were “unfit for human habitation.” He ordered an immediate end to the trusty system and all other unconstitutional conditions and practices, including the beating and shooting of prisoners; the deprivation of mattresses, hygienic materials and adequate food; the practice of handcuffing or otherwise binding inmates to fences, bars, or other fixtures; and the use of cattle prods to keep prisoners standing or moving, as well as several other inhumane practices. (Gates v. Collier)

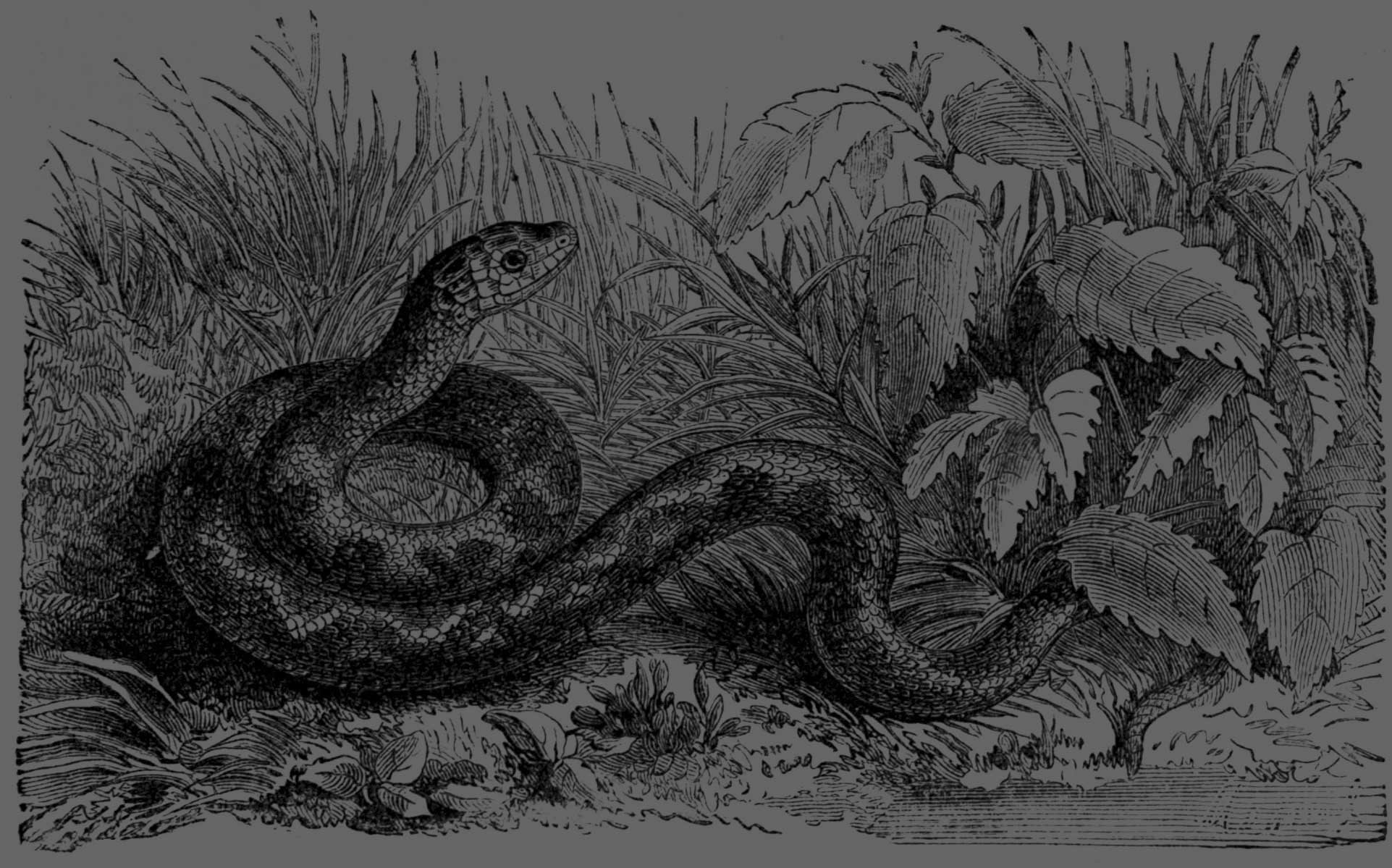

“Sometimes I think it done changed. And then I sleep and wake up, and it ain't changed none...It's like a snake that sheds its skin. The outside look different when the scales change, but the inside always the same.”

“Sometimes I think it done changed. And then I sleep and wake up, and it ain't changed none...It's like a snake that sheds its skin. The outside look different when the scales change, but the inside always the same.”

Jesmyn Ward Author of Sing, Unburied, Sing

Williams, who visited her uncle at Parchman during his wrongful incarceration, prays she never has to return to Parchman again.

“I can’t do it again,” she told the Innocence Project, recalling the two-hour drive there and back where she would witness men, hunched over, harvesting crops field after field. Williams said even visitors were treated poorly and subjected to invasive searches.

“They even checked the baby’s diaper,” she recalled. And, on top of that, the indescribable pain of leaving the person you love behind in that place of suffering.

Today, incarcerated people at Parchman still work in the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed and tended, only the cotton has been replaced by fruits and vegetables. The fieldwork, according to Mississippi’s Department of Corrections, is supposed to address “inmate idleness.”

Parchman remains a site of forced labor, deadly violence, and unsanitary conditions. Recent videos and photos have exposed inhumane conditions that match those from a century ago: Rat-infested cells without power or mattresses, unusable showers and toilets, and unidentifiable food. Nine deaths were reported in January 2020, including due to stabbings, beatings, and suicide.

Parchman. Left: a shower with damaged walls; top right: a shower with missing ceilings and knobs; bottom right: a backed up shower drain. One building had a single working shower for more than 50 inmates. (Parchman 2019 Health Inspection Report).

These stories are not limited to Parchman. Across the United States, where there are more than two million incarcerated people — the overwhelmingly majority poor and disproportionately Black and brown — human beings labelled “convicts” and “inmates” routinely live and die in inhumane conditions. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division released a 53-page report on Alabama’s men’s prisons. Page after page detailed accounts of beatings, murders, sexual assaults, and drug overdoses.

In May 2016, for example, officers found a strangled prisoner “lying face down in his bed … his face was flattened, indicating that he had been dead for quite some time. At some point, the assailants appeared to have urinated on the victim.”

Brutal conditions also exist in America’s jails, where people presumed innocent are held awaiting trial. According to a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1,071 people died in local jails in 2016. The leading cause, suicide, accounted for nearly one-third of those deaths.

The 13th Amendment continues to permit the enslavement of prisoners, who are still required to work for little or no pay in various public and private industries. In 2010, a federal court held that “prisoners have no enforceable right to be paid for their work under the Constitution.” Yet, across the country, prison labor remains essential to running prisons and services beyond prison walls. They cook and clean, work in fields, manufacturing warehouses, and call centers, fight wildfires, do commercial laundry, make masks and hand sanitizer, sometimes for as little as two cents an hour —if anything — often under threat of punishment.

Taken together, these accounts provide a grim picture of the injustices inside, and outside, of our nation’s jails and prisons, where the vestiges of slavery live on through updated modes of state-sanctioned violence, neglect, and coerced labor. As Angela Y. Davis observes in Are Prisons Obsolete? “[Prison] relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.”

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

May 10, 2025 at 3:19 pm

I had no idea what Parchman Prison was until today. I was researching blues songs and came across Bukka White’s song. I am saddened and angered that this happened, let alone learning the prison is still in operation. I cannot understand why a first world nation cannot behave like one. We have so far to go.