Why Bite Mark Evidence Should Never Be Used in Criminal Trials

Nearly a quarter of people exonerated since 1989 were wrongfully convicted based on false or misleading forensic evidence, like bite marks.

Special Feature 04.26.20 By Daniele Selby

In May 1992, Noxubee County, Mississippi, was rocked by the discovery of the body of three-year-old Christine Jackson in a creek about 500 yards from her home. Two nights before, Jackson had been taken from her home in the middle of the night, raped and murdered.

Police found no signs of forced entry, which led them to suspect that the person who abducted the child must have been in the home. Police ignored the fact that a window near the child’s bed was broken and, therefore, could not be locked for safety. They soon arrested Kennedy Brewer, Jackson’s mother’s boyfriend.

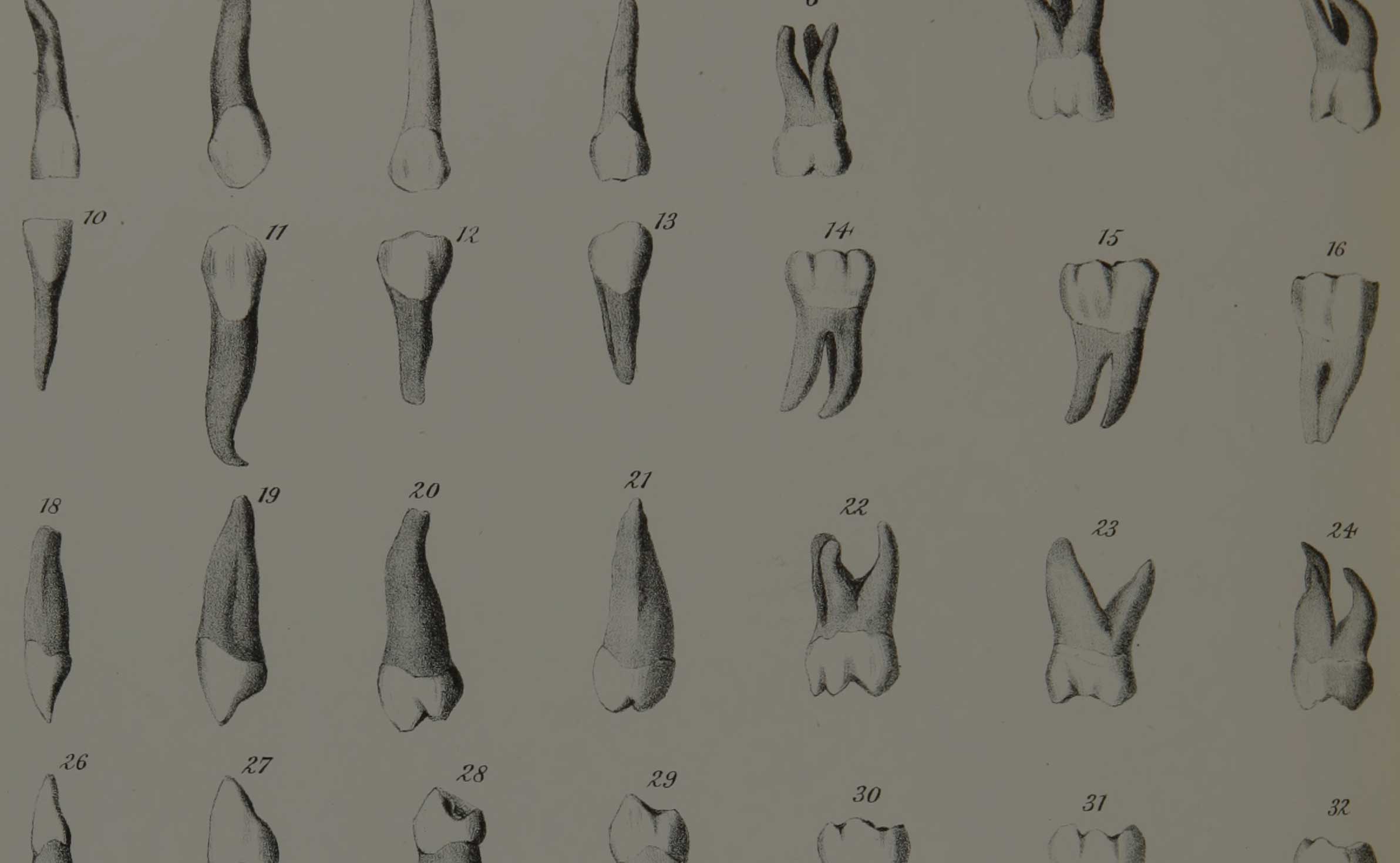

Though a semen sample was recovered from the girl’s body, it was insufficient for DNA testing at the time. So the prosecution focused on the 19 marks found on the child’s body, which medical examiner Steven Hayne said he believed to be bite marks. Hayne called on Dr. Michael West, a forensic odontologist, to examine the marks on the girl’s body.

Dr. West was certain that the marks on Jackson’s body came from teeth and that those teeth “indeed and without a doubt” belonged to Brewer.

In fact, Dr. West matched Brewer’s teeth to the marks on Jackson’s body and excluded all other potential sources, a degree of certainty that is simply impossible because bite mark evidence has never been scientifically validated. Bite mark “experts” cannot even agree on the answer to the most basic of questions: Was this injury caused by teeth?

Despite conflicting testimony from another forensic dentist, Brewer was convicted and sentenced to death, almost entirely on Dr. West’s testimony.

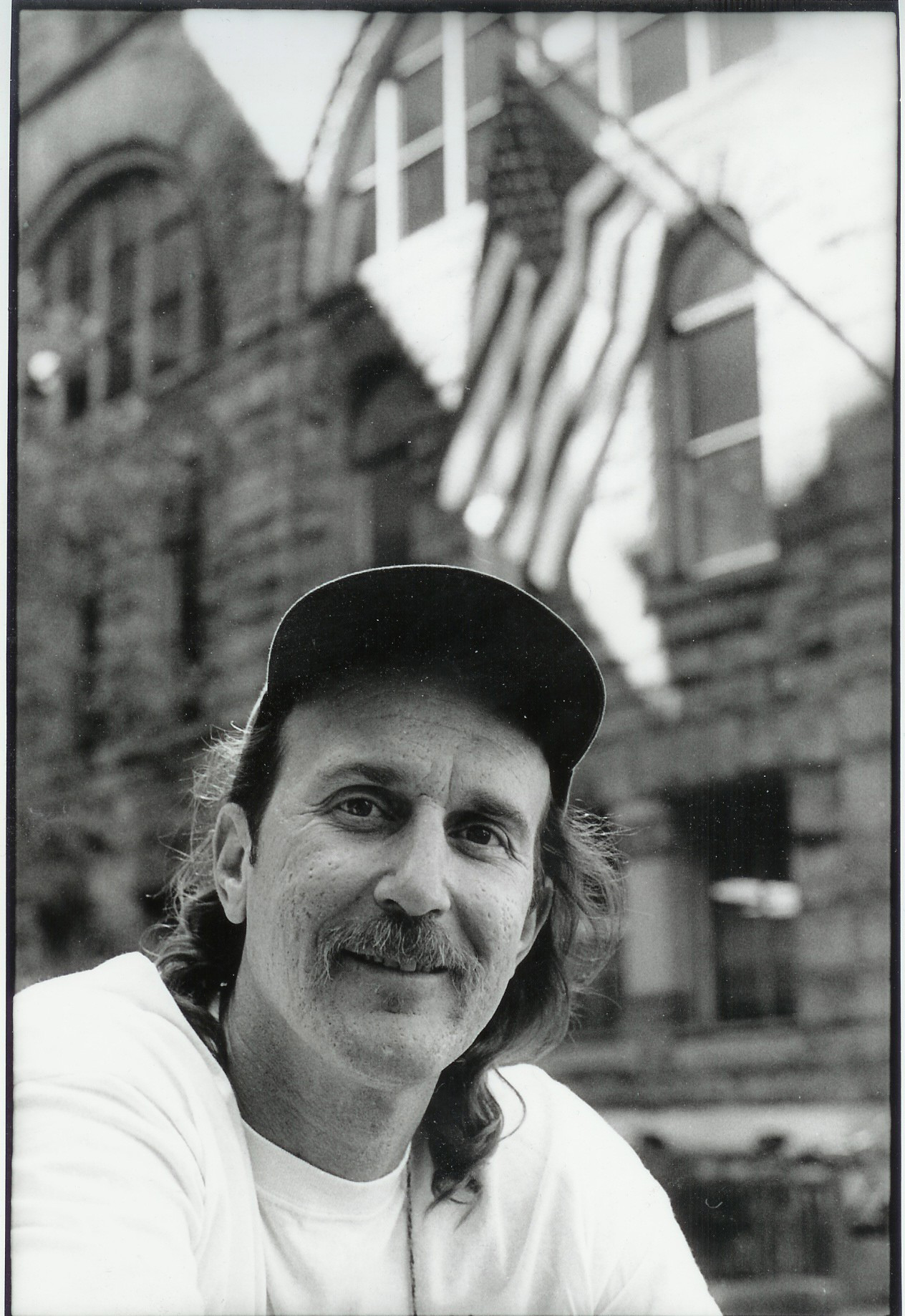

Brewer, who is featured in Netflix’s new documentary series “The Innocence Files,” spent 15 years in prison, seven of those years on death row, for a crime he did not commit. In 2008, he and Levon Brooks, a man convicted of a very similar crime that also took place in Noxubee County two years before Jackson’s murder, were exonerated together with the help of the Innocence Project.

26

people have been wrongfully convicted based on bite mark evidence (The Innocence Project)

Bite marks played a key role in the wrongful convictions of both Brewer and Brooks. At least 24 other people have been wrongfully convicted, arrested, or charged based on the use of bite mark evidence, but there are likely many more innocent people behind bars because of the use of this discredited science. Here’s everything you should know about bite mark evidence.

Bite mark analysis has never been validated

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences released a groundbreaking report detailing problems with many forensic techniques in use in criminal proceedings. The report raised issues about the “substantial rates of erroneous results” in forensic disciplines including bite marks, and highlights its lack of scientific validation.

Six years after this report, Drs. Iain Pretty and Adam Freeman, the former president of the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO), alarmed by an uptick in wrongful convictions based on bite mark analysis, set out to determine whether they could establish the reliability of their work. They carried out a study which asked ABFO-certified dentists to use a “decision tree” to analyze sets of bite marks — some from their own case files. Among other basic questions, they were asked to determine whether they were looking at a “bite mark,” something “suggestive of a bite mark,” something that was “not a bite mark,” or whether they had insufficient information to make a determination.

In all but a few cases, participants could not agree on whether or not they were looking at a bite mark.

“That was so horrifying. If experts can’t agree on the answer to that initial question: Is this or is this not a bite mark? That should trouble anybody,” Dr. Freeman emphasized.

After years of practicing bite mark analysis, Dr. Freeman decided that day to stop. Unlike Dr. West, who consistently used definitive language in proclaiming injuries to be bite marks on multiple occasions, Dr. Freeman said he never once felt comfortable enough to testify about the probability of a bite mark “match” in any case.

“If experts can’t agree on the answer to that initial question ... That should trouble anybody.”

“If experts can’t agree on the answer to that initial question ... That should trouble anybody.”

Dr. Adam Freeman Former President of the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO)

Dr. Freeman continues to work as a dentist and forensic odontologist, examining teeth and dental records to help identify bodies in cases such as mass disasters, and testifying in court about the lack of scientific validity underlying bite mark evidence. He also appears in “The Innocence Files.”

But Dr. Freeman hasn’t been the only one to reject the use of bite mark analysis. Dr. Pretty, Dr. Cynthia Brzozowski and many other forensic dentists have also come to reject the discipline as unreliable.

Additionally, the Texas Forensic Science Commission called for an end to the use of bite mark testimony in criminal trials in 2016, after conducting a six-month investigation into its usage and determining that it “does not meet the standards of forensic science.” The move came after the Texas Court of Appeals vacated the murder conviction of Steven Chaney, whose wrongful conviction was based nearly entirely on bite mark evidence. Still, bite mark evidence continues to be admissible in courts across the country.

The problem with bite marks

Human dentition — the way in which our teeth are arranged — has not been proved to be unique to each individual. But, more fundamentally, the problem with using bite marks on bodies to identify perpetrators of crimes is that skin is a terrible recording medium for a bite mark.

In the Brewer case, Dr. West not only wrote in his report that the marks on the victims’ bodies were human bite marks, but that he was sure that they belonged to Brewer. As explained in “The Innocence Files,” the marks were likely left by crawfish that bit Jackson’s body after she was left in the creek.

It’s hard to determine the source of marks on a body because “what we’re looking at isn’t actually a bite mark indentation, we’re looking at the bruise that’s left over,” Dr. Freeman explained. “And a bruise doesn’t exactly approximate the teeth that made it because bruises are diffuse areas of blood under the skin … and some people bump into things and bruise easily, and others don’t.”

He added that skin is elastic, and this elasticity varies depending on how much fat a person has in their body or how old they are. Skin also holds tension and releases in different ways as you move, which would affect the impression teeth might leave on a person.

This means that if the same person bit two different people, the impressions or bruises they would leave wouldn’t necessarily match. And the way that these factors impact bite marks have never been studied among living people and likely never will be.

“You’re never going to get approval to do a study where you say, I’m going to bite 1,000 people and some of those people are going to have cancer or diabetes or sickle cell anemia, some of those people are going to be Black and white and Greek,” Dr. Freeman said.

1 in 4

people exonerated since 1989 were wrongfully convicted based on false or misleading forensic evidence. (National Registry of Exonerations)

Why is bite mark evidence still being used?

“The scientific evidence is really clear that bite mark evidence can never be used,” Innocence Project strategic litigation staff attorney Dana Delger said. “But what we see in bite mark cases — what we see in discredited science cases generally — is that there’s an extreme mismatch between the law and science, and how they work together in the law.”

Courts generally look back on the previous decisions of other courts for reference when determining how to apply law, Delger explained.

“The notion is that the law shouldn’t really change very much — if that was the law yesterday, then it should be the law today, and it’ll be the law tomorrow — but that isn’t how science works at all,” she said.

Science changes rapidly with new information and research, but laws do not. That is one of the major hurdles in keeping bite mark comparison evidence out of criminal proceedings. And despite the rising chorus of voices in the scientific community and beyond calling out the unvalidated use of bite marks, some continue to believe in bite mark evidence and the ABFO still supports its use.

“That kind of recalcitrance can make it really hard to fight the battles we need to fight to exonerate our clients,” Delger said.

Eddie Lee Howard is one of these clients. Howard was convicted of the 1992 rape and murder of an 84-year-old woman in Mississippi. Though he always maintained his innocence, he was convicted in 1994 and sentenced to death.

Howard’s conviction was largely based on the testimony of Hayne and Dr. West — the same so-called experts who testified in Brewer’s case. Initially, Hayne did not report seeing bite marks on the body. However, after then-district attorney Forrest Allgood — also the prosecutor in Brewer and Brooks’ cases — identified Howard as the primary suspect in the case, Hayne said he had seen marks that could be bite marks. The victim’s body, which had already been buried at this point, was then exhumed and examined by Dr. West, who proclaimed that the marks were indeed bite marks and that they matched Howard.

“The scientific evidence is really clear that bite mark evidence can never be used.”

“The scientific evidence is really clear that bite mark evidence can never be used.”

Dana Delger Innocence Project Strategic Litigation Staff Attorney

Just two years later, Dr. West became the first person to be suspended from the ABFO, and by 2006 he was forced to resign from the American Board of Forensic Pathology. Still, that same year, in response to an appeal, the Mississippi Supreme Court wrote of Dr. West’s testimony in Howard’s case: “Just because Dr. West has been wrong a lot, does not mean, without something more, that he was wrong here.”

But the Innocence Project and the Mississippi Innocence Project continued to push for DNA testing of crime scene evidence. Tests done on the knife used in the crime and the victim’s nightgown in 2014 provided further evidence of Howard’s innocence. Yet, he remains on death row today for a crime he did not commit because wrongful convictions are so difficult to overturn. The Innocence Project is still fighting for justice on Howard’s behalf, and his appeal is currently being considered by the Mississippi Supreme Court.

Nearly a quarter of the 2,601 people who have been exonerated since 1989 were wrongfully convicted based on false or misleading forensic evidence, like bite marks, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

How to end to the use of bite mark evidence

By adopting changed science statutes, states can pave the way for people wrongfully convicted based on bite mark evidence to seek justice. Such statutes create a path for innocent people to bring their cases back into court when the science used to convict them has changed or, as in the case of bite marks, been invalidated.

So far, six states — California, Connecticut, Michigan, Nevada, Texas and Wyoming — have adopted “change in science” statutes or court rulings to set this precedent after the Innocence Project and members of the Innocence Network lobbied for these crucial reforms. And you, too, can play a role in advancing justice by advocating for these legislative changes when such bills are being considered by your lawmakers.

While changed science statutes enable people who are wrongfully convicted to come back to court to have their cases reviewed, they don’t prevent people from being wrongfully convicted based on flawed forensic science in the first place.

Though the science behind bite marks has been debunked, it continues to be used in courts. And when presented as scientific evidence by so-called experts in court, bite marks seem to offer jurors a false sense of certainty.

Part of the problem, Delger said, is that most lawyers — defense attorneys and prosecutors — and judges aren’t versed in the science behind the evidence. But they should be.

“If you want to not only change what’s happening with bite marks, but to stop the next bite marks from getting into court, that requires judges to be extremely skeptical and thorough when they are considering the admission of scientific evidence,” Delger said.

“The stories of the men and women that have been exonerated, who were convicted based on what we now know to be faulty evidence, tell us that that is something we have an obligation to do — to really get in and understand the science so we can know whether we’re using something good or bad.”

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.