Freedom at a Cost: The Devastating Case of Corey Williams

06.06.18 By Innocence Staff

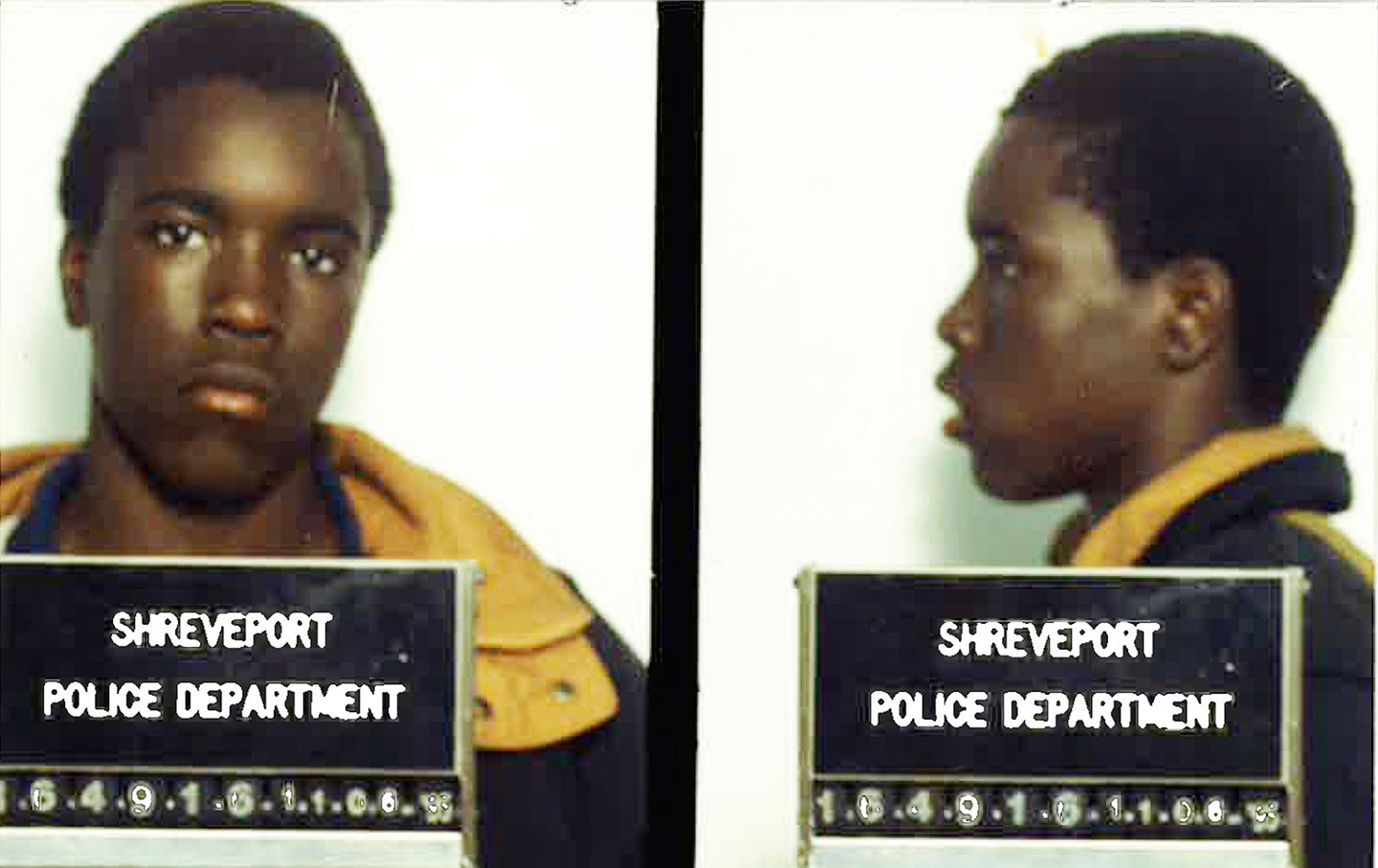

On Monday, The Nation published an article that explores the devastating case of Corey Williams. In January 1998, Williams was in his neighborhood in Shreveport, Louisiana, when a pizza delivery driver was fatally shot. Williams—a black 16-year-old with a severe intellectual disability—ran home after he learned of the shooting. When police located Williams and brought him in for questioning, he was interrogated for 12 hours before he ultimately confessed to the murder.

In October 2000, Williams was convicted and sentenced to death, even though no physical evidence tied Williams to the crime and he insisted his confession was false. He was later resentenced to life in prison after a judge ruled that Williams was intellectually disabled and thus not qualified for the death penalty.

Related: Why Do Innocent People Confess?

In May 2018, the Caddo Parish District Attorney’s Office offered to release Williams in exchange for a manslaughter plea. Believing this was the best possible outcome for Williams, his attorneys agreed to the deal. Although accepting the plea ensured Williams’ freedom, it also guaranteed that Williams would suffer the collateral consequences of having a murder conviction on his record, namely, Williams would not be eligible to receive compensation for the 20 years he wrongly spent in prison.

Although accepting the plea ensured Williams’ freedom, it also guaranteed that Williams would suffer the collateral consequences of having a murder conviction on his record.

Still, the question remains: how did Williams—a 16-year-old with an intellectual disability—get sentenced to death for a crime he did not commit? According to The Nation, the answer was in the prosecution’s hands all along.

Hugo Holland, a Caddo Parish assistant district attorney, was responsible for Williams’ conviction. Before Williams, Holland had tried dozens of death-penalty cases and put at least 10 people, most of whom were men of color, on death row. Years later, half of Holland’s death-penalty convictions were overturned, and two are awaiting appeals. In three of those cases, including Williams’, Holland was accused of withholding evidence.

Related: Take the Quiz: What Do You Know about Prosecutorial Misconduct?

Holland was fired as a Caddo Parish assistant district attorney in 2012, but he quickly found a well-paying job as a prosecutor-for-hire and as a lobbyist for Caddo Parish.

The Nation contacted Holland via email for comment on Williams’ case. Not aware Williams had been released on a plea deal, he responded: “We didn’t conceal anything. That’s horseshit. Didn’t know he was out. He shouldn’t be. He is a murderer.”

In 2015, Williams’ attorneys obtained evidence that prosecutors had hidden for nearly 20 years: tapes of interviews with witnesses to the crime. At trial, Williams’ defense attorneys were unaware of the tapes’ existence, so they relied on “summaries” of the witness statements. These “summaries” seemed to have been changed to make Williams appear guilty.

Related: Brady v. Maryland

Upon listening to the tapes, Williams’ lawyers learned that multiple eyewitnesses, including the original investigating officers, believed in Williams’ innocence. An interview with another witness suggested that Chris Moore—the prosecutor’s star witness against Williams and the person whose gun was used to shoot the victim—was guilty, not Williams.

When Williams’ lawyers appealed his case for the second time to the U.S. Supreme Court, they argued that without the tapes, they were unable to present an “effective” defense at trial.

According to The Nation, the deal Caddo Parish offered Williams is not uncommon. “The Manslaughter settlement,” writes The Nation, “allows everyone involved to save face: no one accepts responsibility, and Williams is released.” It’s understandable why Williams took the deal: proving his innocence could have taken years, and he suffered sustained abuse in prison due to his intellectual disability.

“As for Hugo Holland,” concludes The Nation, “he continues to collect his paycheck, a prosecutor not in the least chastened by his errors, but, rather, emboldened that he was almost able to get away with murder.”

And while Holland continues about his daily business, Williams is out-of-prison, having lost 20 years of his life, without financial resources or work experience—but with a manslaughter conviction on his record.

And while Holland continues about his daily business, Williams is out-of-prison, having lost 20 years of his life, without financial resources or work experience—but with a manslaughter conviction on his record.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.