From Emmett Till to Pervis Payne — Black Men in America Are Still Killed for Crimes They Didn’t Commit

Innocence Project client Pervis Payne is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 3, in Tennessee.

07.25.20 By Daniele Selby

Updated on Aug. 5, 2020 at 5:00 p.m. ET: On July 30, Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich announced that her office is opposing DNA testing of evidence in Pervis Payne’s case. Weirich also said that evidence presented to Payne’s legal team in 2019 — previously referred to in this article as “hidden evidence” — is actually from another case and was shown to Payne’s team in error. This article has been updated to reflect this new information.

Emmett Till, a young Black boy in Mississippi, turned 14 on July 25, 1955. Almost exactly one month later, he was brutally murdered after being accused of sexually harassing Carolyn Bryant, a white woman, in a grocery store.

Till would have turned 79 today had he not been killed. The two white men accused of his murder were later found “not guilty” by an all-white, all-male jury. Four months after the trial, which took place in a segregated courtroom, the two men admitted to kidnapping and murdering Till in an interview with Look magazine. Because they had already been acquitted, they could not be tried again. Neither ever served time for Till’s death.

Six decades later, Bryant admitted that she had lied and that the parts of her accusation considered most incendiary at the time — that Till had grabbed her and made verbal and physical advances on her — were untrue. Bryant has never faced any legal consequences for her accusations against Till. The FBI opened a reinvestigation into his murder three years ago.

Till’s story of injustice might have been lost to history if his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, hadn’t insisted that the world take notice of her son. When Till’s body was found in the Tallahatchie River days after the teen had been abducted from his great uncle’s house, it was unrecognizable. His great uncle was only able to identify his body — disfigured from being beaten, shredded with barbed wire, shot, and thrown in the river — by his father’s initialed ring, which he still had on his finger.

“Let the people see what they did to my boy,” Till-Mobley said when she saw her son’s body. She insisted on an open casket for his funeral so that the public would have to contend with the heinous crime carried out against her son and so many other Black Americans throughout history.

Related: Read Mamie Till-Mobley’s book “The Death of Innocence”

More than 4,700 people were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968, according to the NAACP. The vast majority were Black, while many of the white victims of lynching were killed for helping Black people, advocating for their rights, or for speaking up against the lynching of Black people.

Though Till’s story has not been forgotten, such racism and inequality persist today and contribute to injustice in the legal system and beyond. From the Scottsoboro Boys, who were wrongly convicted of raping two white women, to the “Exonerated Five” to Christopher Cooper, the man a white woman falsely told police had threatened her life in May, Black and brown men in America have continued to be perceived as dangerous, violent, and hypersexual. The harmful and racist stereotypes of Black men as predators has contributed to Black men being incarcerated at higher rates and to wrongful conviction.

“Let the people see what they did to my boy.”

These are the same kind of racist stereotypes that the prosecution in Pervis Payne’s case evoked at trial to convict him of murder. Payne, who has an intellectual disability, has spent 32 years facing execution in Tennessee for a crime he has always said he did not commit — and DNA testing of evidence in his case could help prove this. The Innocence Project jointly filed a petition for DNA testing on July 22.

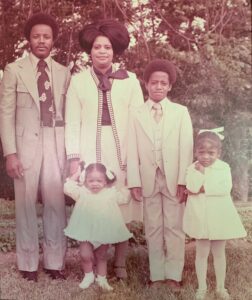

Pervis Payne (second from right) with his family. (Photo: Courtesy of the Payne family).

Payne was convicted for the 1987 murder of Charisse Christopher and her child in Millington, Tennessee. The prosecution argued that Payne had been searching for sex after using drugs and looking at a Playboy magazine, and that he attacked Christopher after he made an advance on her and she rejected him. But no evidence supports this theory.

Though Payne’s mother begged law enforcement to administer a drug test to her son to prove that he had not been using drugs, they refused. Payne had no history of drug use, no criminal record, and was not known to be violent. In fact, those who know him describe him as a kind and respectful man, who liked to make his family laugh and help out at his father’s church.

Read more: 8 Things You Need to Know About Pervis Payne’s Case

But the prosecution painted a very different picture, making Payne out to be a violent and hypersexual drug user. And, at trial, the prosecutor repeatedly pointed out the victim’s “white skin” when referring to parts of her body, a poignant reminder of her whiteness in a county ranked among the 25 counties with the most recorded lynchings between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

In the late 1800s, claims that Black men had raped or made sexual advances on white women were frequently cited to justify their lynchings. Historians say that in reality many rape accusation claims were false and were often used as cover for consensual relationships that were, at the time, extremely taboo. And racist beliefs were so deep-seated among white communities, that “Whites could not countenance the idea of a white woman desiring sex with a [Black person], thus any physical relationship between a white woman and a [B]lack man had, by definition, to be an unwanted assault,” writes historian Philip Dray.

The perception of Black men as a danger to white women in particular, contributing to false accusations like the ones lobbied against Till and the Scottsboro Boys, is deeply rooted in this history and the legacy of slavery. In Louisiana, for instance, rape was only considered a crime when the victim was a white woman, according to the American Bar Association, and capital punishment was a mandatory punishment for rape and attempted rape only when the alleged attacker was a slave (and Black).

Payne had no history of drug use, no criminal record, and was not known to be violent.

In Alabama, the court allowed juries to consider a defendant’s race and to rely on social stereotypes about that race — like the prevalent belief at the time that Black men are prone to raping women — to infer the defendant’s intent to commit a crime.

Today, Black men are twice as likely to be arrested for a sex offense and three times more likely to be accused of rape than white men, the Appeal reported. That’s not because they are committing such crimes at higher rates than people of other races or ethnicities, but because they are more often suspected and accused of such crimes due to racial biases.

Pervis Payne in Riverbend Maximum Security institution in Tennessee. (Photo: Courtesy of PervisPayne.Org).

All too often, Black men are presumed guilty by law enforcement and the public, contributing to wrongful convictions and harsher sentences when found guilty. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people. And studies show that Black men are sentenced to death far more often when accused of committing a crime against a white person. Since 1976, nearly 300 Black people accused of murdering white people have been executed — about 14 times the number of white people executed for murdering white people, the Death Penalty Information Center reported.

Payne, a Black man, is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 3, for the murder of Christopher, a white woman. But DNA testing that could be completed within 60 days, could prove what he’s been saying for three decades: He’s innocent.

His life, like Till’s, should not be unjustly taken.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

August 12, 2020 at 9:16 am

August 4, 2020 at 8:27 pm

Please do the

DNA testing…it is the right and just thing to do!!!

I know that God is going intervene on his behalf because this is unjust and this man should be set free and DNA testing should have been used to prove his innocence. This has been going on two long , innocence black men convicted of crime that they did not commit, and society going along with killing of black men for no reason.