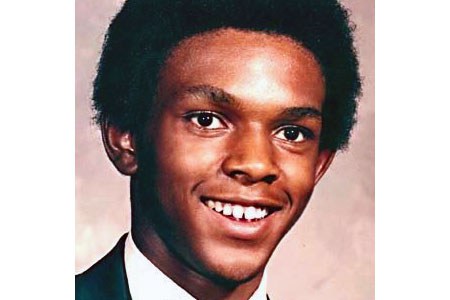

Timothy Cole

Timothy Brian Cole died in a Texas prison in 1999 while serving a 25-year sentence for a rape he didn’t commit. Nearly a decade later, DNA evidence from the crime posthumously exonerated Mr. Cole and implicated another man as the attacker.

The Crime

On March 24, 1985, 24-year-old Texas Tech student Michele Mallin was parking her car in a church parking lot across from her dormitory in Lubbock, Texas, when an African American man approached her and asked her to help him start his car with jumper cables. When she said she didn’t have cables, the man reached in through her window and unlocked the door. The woman screamed and bit the man’s thumb, but then noticed that he had a knife. Holding the knife to her throat, he forced her to lay down in the car while he moved into the driver’s seat.

He drove to a vacant field outside of town, where he forced her to perform oral sex and then vaginally raped her. The attacker then drove the car back to Lubbock, where he took $2 in cash, a ring and a watch from Ms. Mallin and left on foot. Ms. Mallin then called police and reported the attack.

The Investigation

Ms. Mallin, who is white, described the attacker to police as a young African American man wearing a yellow shirt and sandals, but didn’t give many other details. She said the attacker had smoked cigarettes throughout the attack.

Police believed at the time that Ms. Mallin’s attacker may have been an unknown serial rapist known at the time as the “Tech Rapist” and suspected in four other attacks, and nine officers began conducting surveillance around campus. Composite sketches based on the descriptions from the victims appeared in the Texas Tech campus newspaper.

Mr. Cole was a 26-year-old Army veteran studying business at Texas Tech in 1985. On the night Ms. Mallin was raped, he had studied at home, where his brother was hosting a card game.

Two weeks after Ms. Mallin was attacked, Mr. Cole went to a pizza restaurant near the Texas Tech campus. The restaurant was also just a few blocks from the scene of the attack, and Mr. Cole spoke with a female detective outside of the restaurant. This conversation made him a suspect, and a detective went to Mr. Cole’s house to take a Polaroid photo of him.

Detectives then showed Ms. Mallin a photo lineup including six photographs. Mr. Cole’s was the only Polaroid; the other five were mug shots. Mr. Cole was looking at the camera in his photo while the subjects in the five mug shots were facing to the side. According to police, Ms. Mallin was immediately sure that Mr. Cole was her attacker, saying: “That’s him.”

The next day, police conducted an in-person lineup with Mr. Cole and four prisoners. Ms. Mallin again identified Mr. Cole, but victims from the similar December and January rapes also viewed the lineup and did not identify him as the attacker.

Based on Ms. Mallin’s identification, Cole was arrested and charged with aggravated sexual assault.

The Trial

Mr. Cole was tried by a jury in Lubbock 1986 for the rape of Ms. Mallin a year earlier. He was never charged with committing the other rapes.

Ms. Mallin testified for the state and identified Mr. Cole in court as the perpetrator. A forensic examiner from the Texas Department of Public Safety testified that an analyst in his lab had examined the rape kit collected from Ms. Mallin at the hospital after the attack. He said the tests had determined that sperm was present on the swabs from Ms. Mallin’s body. Serology testing found evidence of a Type A secretor on the swabs, and the analyst told the jury that both Ms. Mallin and Mr. Cole had type A blood. Ms. Mallin is a secretor, he said, meaning her blood type can be determined from bodily fluids other than blood. Mr. Cole’s secretor status was unknown.

The analyst also testified that his lab had compared foreign pubic hairs collected from Ms. Mallin’s underwear and body during her hospital examination. He testified that the hairs had similar characteristics to Mr. Cole’s pubic hair, but said the analyst conducting the tests could not make a firm conclusion.

Because there is not adequate empirical data on the frequency of various class characteristics in human hair, the analyst’s assertion that hairs are similar is inherently prejudicial and lacks probative value.

Mr. Cole’s attorney presented an alibi defense — that Mr. Cole was studying at home, where his brother was playing cards with several friends, on the night of the crime. His brother and friends testified that Mr. Cole had been at the apartment at the time of the attack. Mr. Cole also presented evidence that he had severe asthma and did not smoke cigarettes.

Mr. Cole’s attorney attempted to enter evidence that similar attacks had continued to occur in the months after Mr. Cole’s arrest, but the judge refused to allow most mentions of the uncharged crimes before the jury. Mr. Cole also attempted to present evidence that a very similar attack had occurred one month before the assault for which Mr. Cole was charged, and that fingerprints from Ms. Mallin’s car in that case did not match Mr. Cole’s fingerprints. The judge also did not allow this evidence before the jury.

After six hours of deliberation, the jury convicted Mr. Cole. The next day, he was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

The Exoneration

Mr. Cole’s initial appeals were denied. In 1995, after the statute of limitations on the 1985 rape had expired, a Texas prisoner named Jerry Wayne Johnson wrote to police and prosecutors in Lubbock County that he had committed the rape for which Mr. Cole had been convicted. Mr. Johnson was serving a 99-year sentence after convictions for two sexual assaults with similar characteristics to Mr. Cole’s conviction.

Mr. Johnson’s letters were not acknowledged. Mr. Cole died in 1999 without ever learning that Mr Johnson was attempting to confess to the crime. The year after Mr. Cole died, Mr. Johnson wrote again to a supervising judge. This time, the case was moved to a different judge and rejected without comment. Eventually, however, Mr. Johnson’s confessions reached the Innocence Project of Texas and Mr. Cole’s family. Attorneys at the Innocence Project of Texas sought posthumous DNA testing in the case and Lubbock prosecutors cooperated. DNA testing conducted on semen from the crime scene excluded Mr. Cole and implicated Mr. Johnson as the attacker. Mr. Cole was cleared by DNA tests in 2008, and at a hearing in February 2009, Mr. Johnson again confessed to the crime before a judge, Mr. Cole’s family, and Ms. Mallin. The Innocence Project joined with the Innocence Project of Texas as co-counsel on the case, and a Texas judge officially exonerated Mr. Cole at an unprecedented posthumous hearing on April 7. 2009. Texas Gov. Rick Perry pardoned Mr. Cole on March 1, 2010.

Since Mr. Cole’s posthumous exoneration, the state of Texas has passed the Timothy Cole Act, increasing compensation paid to exonerees to $80,000 per year served, expanding services offered to the exonerated after their release and adding compensation for the family of an exoneree if cleared after death. The state also created the Timothy Cole Advisory Panel on Wrongful Convictions in 2009 to study the prevention of wrongful convictions across the state.

Ms. Mallin now speaks and writes about the case to raise awareness about misidentifications and wrongful convictions. “I was positive at the time that it was him,” she said at a speech at the Georgetown University Law Center. “I was shocked when I found out it wasn’t him. I joined Tim’s family in working to exonerate him because it was the right thing to do. Timothy didn’t deserve what he got.”

Time Served:

13 years

State: Texas

Charge: Aggravated Sexual Assault

Conviction: Aggravated Sexual Assault

Sentence: 25 years

Incident Date: 03/24/1985

Conviction Date: 09/17/1986

Exoneration Date: 04/09/2009

Accused Pleaded Guilty: No

Contributing Causes of Conviction: Eyewitness Misidentification, Unvalidated or Improper Forensic Science

Death Penalty Case: No

Race of Exoneree: African American

Race of Victim: Caucasian

Status: Exonerated by DNA

Alternative Perpetrator Identified: Yes

Type of Crime: Sex Crimes

Forensic Science at Issue: Hair Analysis

Year of Exoneration: 2009