An Autistic Man Faces Execution: Misdiagnosis, Misjudgment, and a Life on the Line

Robert Roberson, diagnosed with autism after his conviction, faces execution on Oct. 16 due to misjudgments about his demeanor during his daughter’s medical crisis.

08.14.25 By Alyxaundria Sanford

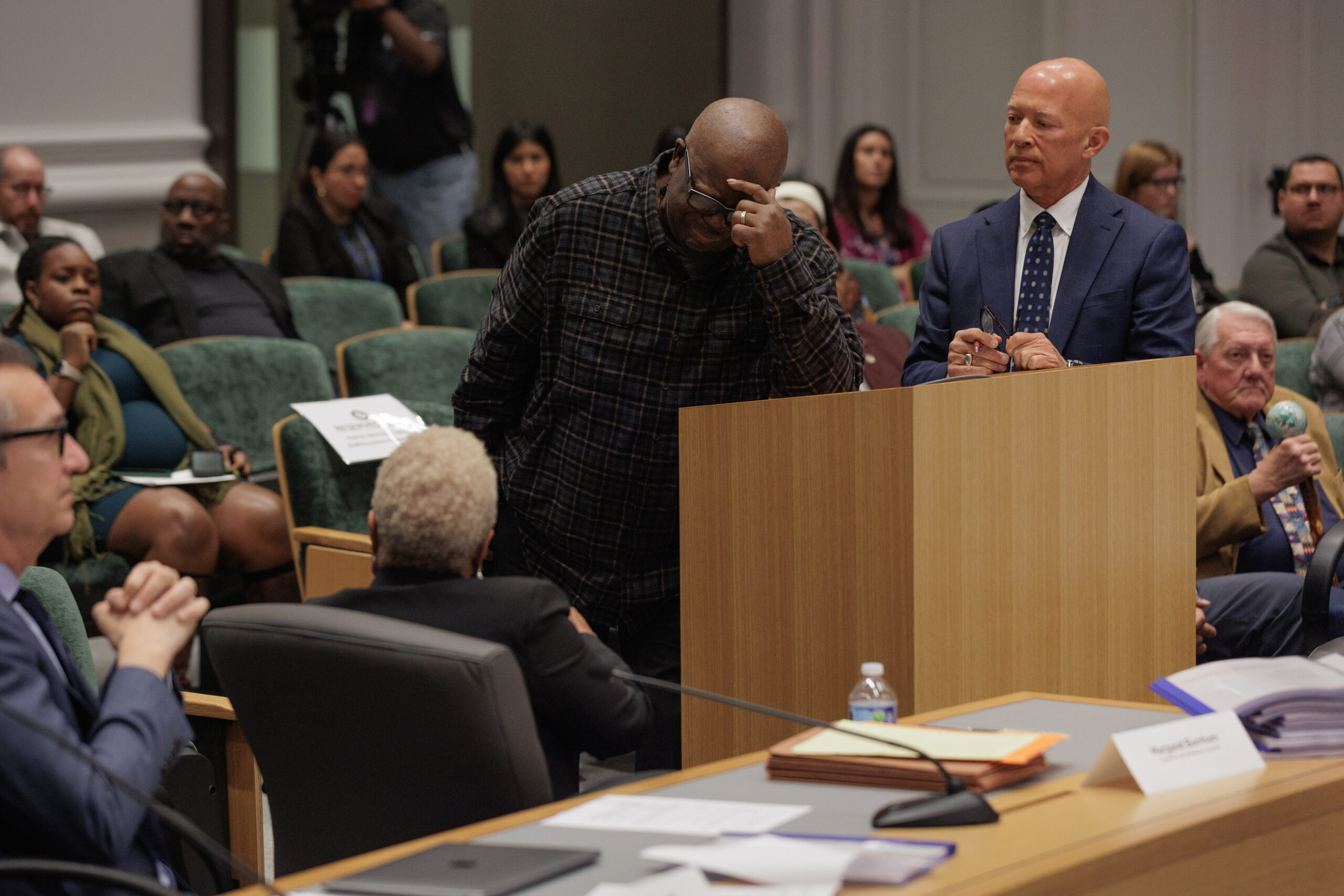

When Robert Roberson brought his unresponsive daughter to the hospital, medical staff became suspicious of his flat affect and interpreted his response to his daughter’s condition as lacking emotion. Former Detective Brian Wharton, who later led the investigation of the child’s death, testified that Mr. Roberson seemed “not right” because he did not display the expected emotional reactions, like anger or sadness, like a “typical” parent.

Mr. Roberson’s lack of visible emotion, or his “flat affect,” is a typical trait of autism. During the 2003 trial for the death of his chronically ill 2-year-old daughter, Nikki, his affect, along with other autism-related behaviors he displayed during the course of the investigation, was used to paint him as cold and remorseless. In fact, he was a loving, dedicated father who simply could not express emotion as neurotypical, or non-autistic, people do. It was not until 2018 — well after he was wrongly convicted — that Mr. Roberson was evaluated and officially diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Watch this powerful New York Times video where former Detective Brian Wharton, who once testified against Mr. Roberson, visits him in prison and now believes in his innocence:

To date, Mr. Roberson has spent 22 years on death row. Convicted on the basis of a now discredited shaken baby syndrome hypothesis, he faces execution in Texas, yet again, on Oct. 16, for a crime that never occurred. His case illustrates how the criminal legal system’s failure to understand autistic behavior can contribute to devastating, life-threatening consequences.

“Robert’s disability directly contributed to his wrongful conviction when investigators assumed his flat demeanor during pronounced stress (a manifestation of his Autism) was a sign of culpability,” Mr. Roberson’s attorneys wrote in their Sept. 17, 2024 clemency petition.

Mr. Roberson was almost wrongfully executed on Oct. 17, 2024, but a bipartisan group of Texas lawmakers intervened. Last month, Mr. Roberson’s legal team filed an emergency motion to stay the execution and requested oral arguments to prove his innocence.

If Mr. Roberson’s execution is not stayed, he will be the first person executed in the United States for a conviction obtained using the now widely debunked shaken baby syndrome hypothesis.

People diagnosed with ASD are seven times more likely to have encounters with the criminal legal system than those without the disorder. They face significant risks of wrongful conviction for crimes they didn’t commit — or that never happened — due to inadequate legal representation, communication challenges, and law enforcement bias.

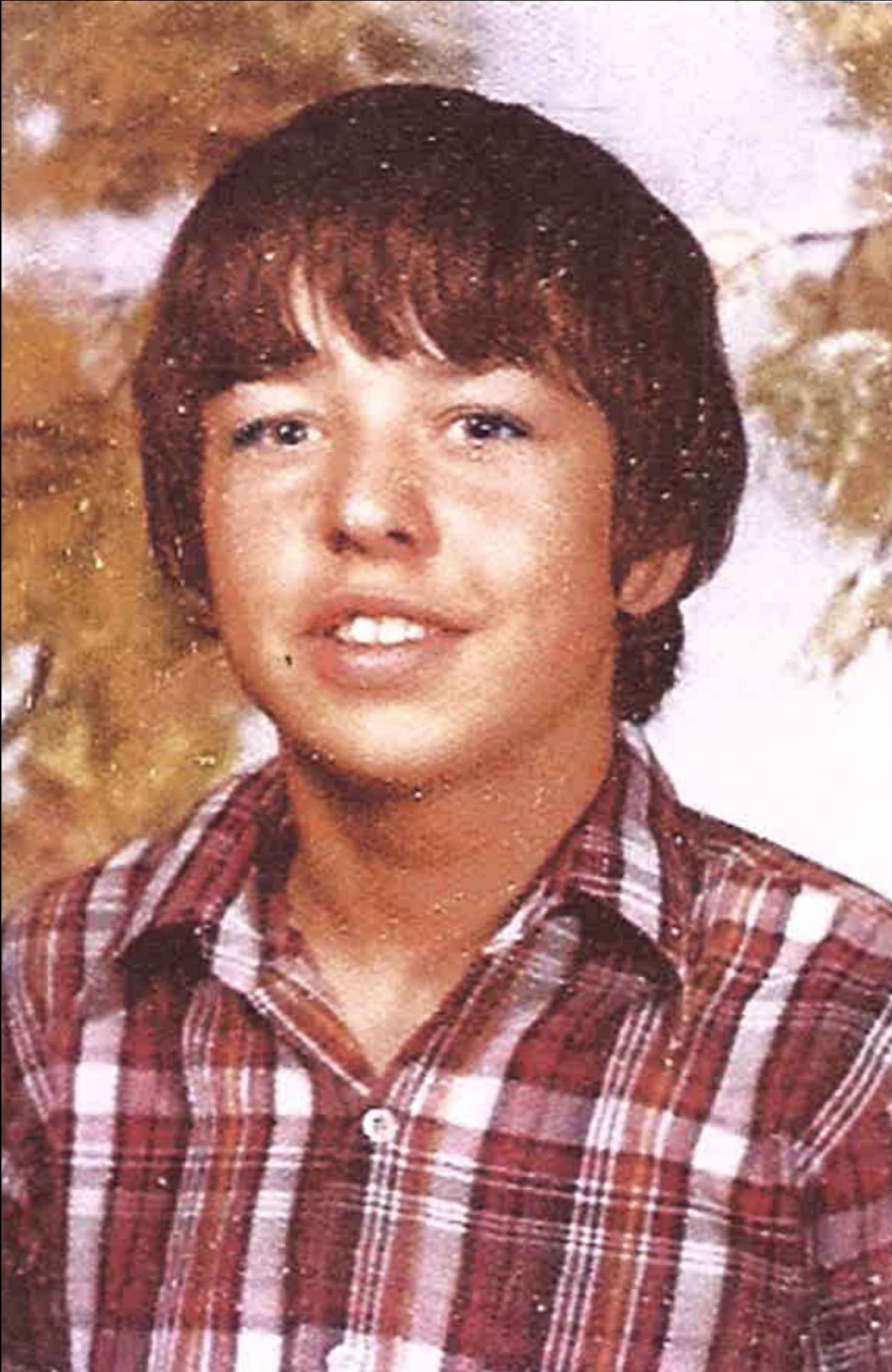

Robert Roberson as a child. (Image courtesy of the Roberson family)

According to Dr. Natalie Montfort, a psychologist who works with people with autism, ASD traits, such as a lack of eye contact, fixation on routine, and nonchalant demeanor expressed during traumatic events are often misunderstood or mistaken for signs of guilt.

In a Houston Chronicle op-ed, Dr. Montfort also argued that Mr. Roberson’s experience growing up in poverty and attending under-resourced schools exacerbated his struggles. He was diagnosed as a “special needs” child, receiving Medicaid assistance for delayed speech and other developmental challenges, but his autism went undiagnosed for the majority of his life even though “his pronounced impairments have been evident his whole life.”

“It’s all too common for people to slip through the cracks this way — particularly people who grow up in poverty and with unstable family circumstances, as Roberson did,” Dr. Montfort wrote.

The failure of medical staff to recognize or respond appropriately to Mr. Roberson’s disability directly led to his wrongful conviction. When medical staff decided it was suspicious that Mr. Roberson was not showing “enough” emotion and was struggling to explain Nikki’s complex medical condition — which he, a former special needs student with a ninth grade education, did not understand — they assumed his presentation meant Nikki had been abused and immediately called the police. She was then transferred to another hospital, where a child abuse expert concluded, without review of her medical records, that the only possible explanation for her condition was shaken baby syndrome, a now-discredited theory that largely formed the basis of Mr. Roberson’s conviction.

Having settled on that theory, police failed to investigate further the child’s medical history that would have revealed a raft of underlying conditions and contributing factors, including chronic pneumonia. Detective Wharton, who now believes Mr. Roberson is innocent, acknowledged that, at the time of the investigation, he “deferred” to medical experts and “followed their lead in explaining what then seemed inexplicable.” But he has come to recognize that the shaken baby hypothesis they relied on to short-circuit the investigation has not withstood the test of time.

“This kind of evidence is complex. And misinformation about the physical evidence developed both at trial and in post-conviction has abounded. Under these circumstances, the district court’s stated rationale for scheduling Robert’s execution now—to ‘move things along’—seems incompatible with the truth-seeking function the public expects in matters of life or death. A stay is necessary to remove the artificial and arbitrary time pressure created by scheduling an innocent man’s execution while he has appeals pending,” stated Gretchen Sween, Mr. Roberson’s attorney.

The state must recognize that Mr. Roberson’s conviction was built on a gross misinterpretation of his behavior and outdated, discredited medical science. It is time to halt this execution and ensure that Texas does not kill an innocent, disabled man for a crime that never occurred.

WATCH: Robert Roberson, Autism & Injustice Panel Discussion

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

October 14, 2024 at 2:27 pm

Thats not fair!! They should let him go because he is innocent and should have freedom!