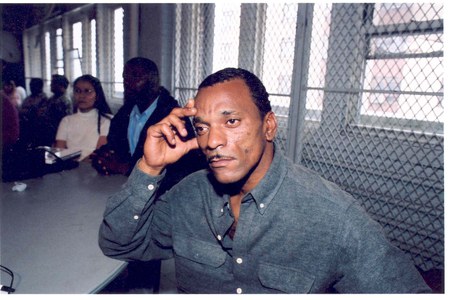

Kevin Byrd

The Crime

On the morning of Jan. 14, 1985, a 25-year-old, pregnant woman was raped at knifepoint in her bed as her two-year-old daughter slept beside her. The encounter lasted about 20 minutes, after which the attacker, a stranger, cut her phone line and fled the scene. The woman gave police a detailed description of the man who raped her, including clothing, facial features, age and height. She also described him as a white male with an unusual brown skin color, a “honey brown color.”

The Investigation

Nearly four months later, the woman was grocery shopping when she spotted Kevin Byrd, a Black man, and told her husband that he was the man who raped her. Despite the inconsistency between her description of the assailant as white and Mr. Byrd being Black, Mr. Byrd was arrested based on her identification.

The Trial

The case against Mr. Byrd was shaky, in part due to poor detective work by the police department whose white officers did not communicate well with the woman, who was Black. The main evidence against Mr. Byrd at trial were the woman’s identification and improper forensic testing. An analyst from the Houston Police Department Crime Lab testified that semen was detected on swabs from the rape kit, and that no blood type could be determined from the swabs. The analyst incorrectly concluded that this result meant the attacker was a non-secretor (a person whose blood type can not be detected in bodily fluids like semen). In fact, it is possible that the attacker was a secretor and that the test simply didn’t discern his blood type. Both Mr. Byrd and the victim were non-secretors, and the analyst testified that only 15-20 percent of people are non-secretors, improperly narrowing the field of possible perpetrators.

When the evidence being tested is a mixed stain of semen from the perpetrator and vaginal secretions from the victim — and testing does not detect blood group substance or enzymes foreign to the victim – no potential semen donor can be excluded because the victim’s blood group markers could be “masking” the perpetrator’s. Under such circumstances, the failure to inform the jury that 100% of the male population could be included and that none can be excluded is highly misleading.

Mr. Byrd was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. The trial judge was so perturbed by the case that he wrote a letter to the chief of police complaining about the manner in which the investigation was conducted.

The Exoneration

DNA test results were not admissible in Harris County courts until 1989, and at the time of Mr. Byrd’s trial, an examination of semen evidence from the crime concluded only that Mr. Byrd could not be excluded as a possible donor.

In July 1997, after DNA tests on this evidence proved that Mr. Byrd could not have committed the rape, the district attorney, sheriff, and the judge who oversaw the trial wrote a letter to then Governor George W. Bush asking him to pardon Mr. Byrd. Despite incontrovertible proof of Mr. Byrd’s innocence, and amidst criticism that his decision was politically motivated, Governor Bush agreed to pardon him only after a court hearing validated the new evidence. Although Mr. Byrd was released from prison in July, he did not receive a pardon from Governor Bush until October 1997.

Mr. Byrd’s case is particularly disturbing, because it was due to pure luck that he eventually was able to prove his innocence. As the evidence warehouse becomes overcrowded, it is standard procedure in Harris County to throw away evidence in old cases where appellate courts have upheld the conviction. In 1994, the trial exhibit with a semen sample that would later free Mr. Byrd was one of many that were slated to be destroyed. The clerk, however, submitted a list of cases where evidence would be thrown away to the district attorney’s office, so they could cross out cases where they wanted evidence preserved. Perhaps by sheer chance, they drew a line through Mr. Byrd’s case and the evidence was saved. To this day, the prosecutors are unsure why they chose to retain the semen sample, and note that it would have been perfectly acceptable, per their guidelines, to have thrown out this crucial piece of evidence back in 1994.

Mr. Byrd spent more than 12 years in prison before he was able to prove his innocence.

Time Served:

12 years

State: Texas

Charge: Rape

Conviction: Rape

Sentence: Life

Incident Date: 01/14/1985

Conviction Date: 01/01/1985

Exoneration Date: 10/10/1997

Accused Pleaded Guilty: No

Contributing Causes of Conviction: Eyewitness Misidentification, Unvalidated or Improper Forensic Science

Death Penalty Case: No

Race of Exoneree: African American

Race of Victim: African American

Status: Exonerated by DNA

Forensic Science at Issue: Flawed Serology

Year of Exoneration: 1997