What to Expect from ‘The Innocence Files,’ Netflix’s New Documentary Series

Special Feature 04.15.20 By Innocence Staff

How do you prove someone is innocent of a crime after they’ve been convicted? How does an innocent person even end up in prison in the first place? “The Innocence Files,” a Netflix original documentary series, delves into these questions, focusing on the cases of eight wrongfully convicted people — Kennedy Brewer, Levon Brooks, Keith Harward, Franky Carrillo, Thomas Haynesworth, Chester Hollman II, Kenneth Wyniemko and Alfred Dewayne Brown — across the U.S.

In nine episodes, the series pulls back the curtain on the work of the Innocence Project, the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, Northern California Innocence Project and The WMU-Cooley Innocence Project at the Thomas M. Cooley School of Law, and the uphill battle their clients face in pursuit of the truth and justice.

“The Innocence Files” dives deep into three major causes of wrongful conviction: the use of flawed forensic science, in this case the debunked “science” of bite mark evidence; the misuse of eyewitness identification; and prosecutorial misconduct. The series’ three parts — The Evidence, The Witness and The Prosecution — devotes three episodes to each topic. The series also explores the roles that race and racism play within the criminal justice system.

“This is truly important television. Each episode reveals – step-by-step – how the American criminal justice system gets it wrong,” Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, Innocence Project co-founders and special counsel told Variety ahead of the series’ release.

“These stories feature people whose freedom was stolen because of governments’ reliance on junk science, discredited and suggestive eyewitness identification procedures, and prosecutors who engage in misconduct to win at any cost,” Neufeld and Scheck, consulting executives on the series, said.

“The Innocence Files” is executive produced and directed by Academy Award nominee Liz Garbus and Academy Award winners Alex Gibney and Roger Ross Williams. Academy Award nominee Jed Rothstein, Emmy Award winner Andy Grieve and Sarah Dowland also direct episodes.

“This is truly important television.”

“This is truly important television.”

Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck Innocence Project Founders

Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck. (Courtesy of the Innocence Project)

Rendering of a jawbone. (Wikimedia Commons)

Part One — The Evidence

The use of bite mark evidence came to public attention after it was used to convict notorious serial killer Ted Bundy. However, though the analysis of bite mark evidence has been portrayed as a valid science in film and on television, a groundbreaking study by the National Academy of Sciences in 2009 debunked its use as a means of positively identifying perpetrators of crimes.

Yet dozens of exonerees were wrongfully convicted based on the use of bite mark evidence, including Levon Brooks, Kennedy Brewer and Keith Harward.

“In almost half our cases, forensic science was misapplied and misused in the initial conviction,” Neufeld says in “The Innocence Files.”

The documentary series not only tells the stories of each exoneree’s personal fight for justice, but also takes a critical look at this once accepted “science” and the forensic odontologists responsible for perpetuating its use, resulting in innocent people being put behind bars.

Among those “experts” is Dr. Michael West, whose “analysis” of bite mark evidence and testimony has contributed to the wrongful conviction of at least half a dozen people. The forensic odontologist expert testimony all but sealed the fate of both Brooks and Brewer. Brooks was convicted of murdering a 3-year-old girl in Noxubee County, Mississippi, in 1990, while Brewer was convicted for a murder following the same pattern two years later.

“Noxubee County didn’t look no further than me — just me,” Brewer says in “The Innocence Files.”

“Then Michael West came in and had me bite down and that was it.” Brewer was sentenced to death.

“Noxubee County didn’t look no further than me — just me.”

“Noxubee County didn’t look no further than me — just me.”

Kennedy Brewer Exonerated after 15 years of wrongful conviction

Kennedy Brewer. (Courtesy of Netflix)

But the extremely similar nature of the two crimes raised questions about whether or not Brooks, who always maintained his innocence, had been wrongfully convicted, and whether or not the bite marks on the victims were human bite marks at all. Innocent black people, like Brewer and Brooks, are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than white people, the National Registry of Exonerations reported.

The Innocence Project took up both their cases and, as a result, Brooks and Brewer, strangers, became uniquely bonded through their fight for justice. While Black people make up just 13% of the U.S. population, they account for 42% of people on death row, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s data, and more than half of the 166 people on death row who have been exonerated since 1973, more than half were black. The Innocence Project team, including attorneys Chris Fabricant, Dana Delger and Vanessa Potkin, all featured in “The Innocence Files,” continues to fight to free people wrongfully convicted based on bite mark evidence and more.

Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer in Noxubee County, Mississippi, in 2015. (Photo: Isabelle Armand)

At least 26 people convicted based on bite mark evidence have since been exonerated.

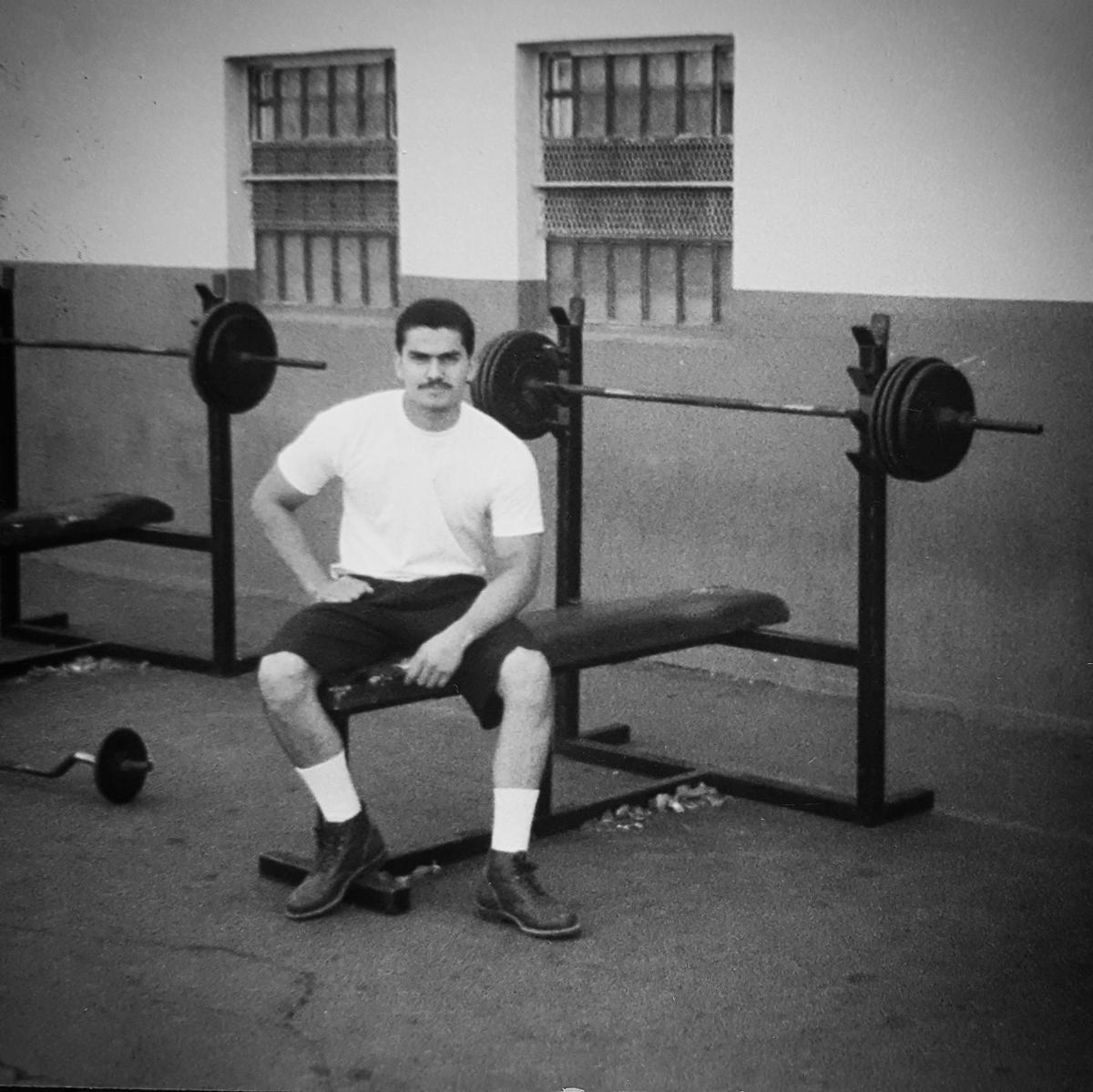

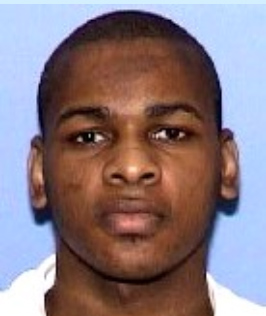

Franky Carrillo in prison. (Courtesy of Franky Carrillo)

Part Two — The Witness

When Franky Carrillo was arrested in 1991 and accused of murder, he had no doubt that this misunderstanding would soon be cleared up. He was innocent.

“In the mind of a 16-year-old boy, it really was no fear, because I knew that although I was cuffed, that I had done nothing wrong,” Carrillo says in “The Innocence Files.” But that soon changed.

Multiple witnesses from a rival gang in Carrillo’s neighborhood in Lynwood, California, identified him as the shooter. However, at trial, the witnesses all gave varying testimony throwing into question whether or not they’d actually gotten a good look at the shooter, resulting in a hung jury and a mistrial.

At Carrillo’s second trial, the same witnesses gave testimonies that matched one another much more closely, and despite the fact that one key witness recanted his statement and said that he had been pressured to testify against him, Carrillo was convicted at age 17 based solely on eyewitness testimony and given a life sentence.

“I felt invisible,” Carrillo says in the documentary. “No one was acknowledging me. No one was asking me specifically what had happened.”

“I felt invisible ... No one was asking me specifically what had happened.”

“I felt invisible ... No one was asking me specifically what had happened.”

Franky Carrillo Exonerated after 19 years of wrongful conviction

Franky Carrillo. (Courtesy of Franky Carrillo)

In 2003, Ellen Eggers, a deputy state public defender took on Carrillo’s case and connected him with the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) and the law firm of Morrison & Foerster, which handled his case pro bono.

Over the next eight years, they worked to clear his name. Ultimately, all the witnesses in Carrillo’s case recanted their statements, admitting that they had been manipulated into identifying Carrillo by police officers or influenced by the suggestion of another witness. In 2011, Carrillo was released and exonerated.

His case shows the influential role a witness’ testimony can have in a case — even ones where witnesses are mistaken or have been coerced into giving false testimony.

Thomas Haynesworth hugging his mother on the day he was released from prison on parole on March 21, 2011. (Courtesy of Netflix)

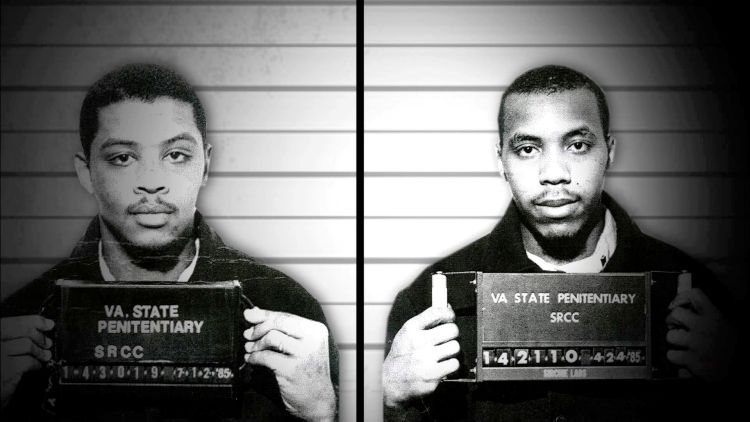

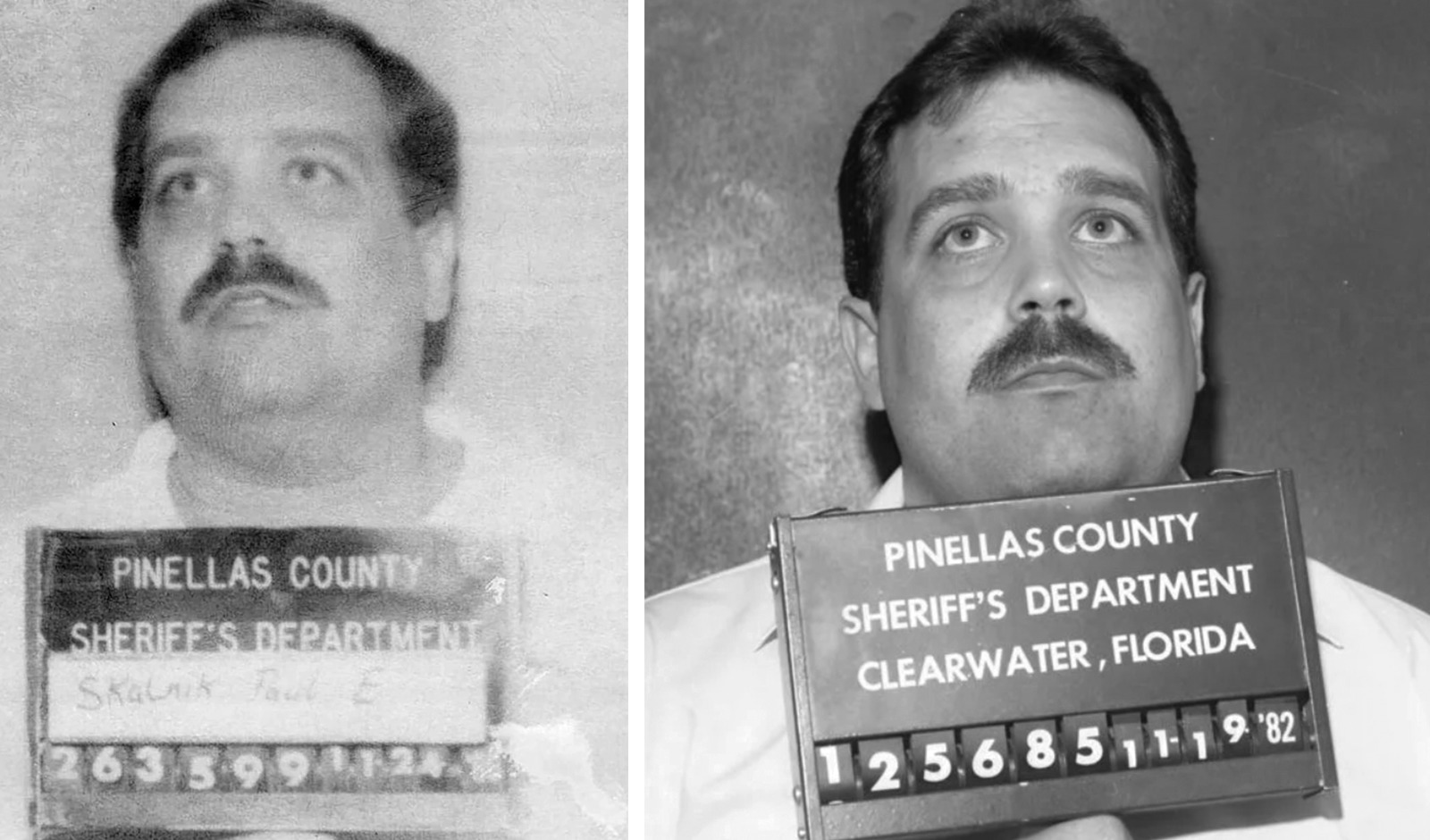

Like Carrillo, Thomas Haynesworth, was also wrongfully convicted in Virginia based on eyewitness testimony, though in Haynesworth’s case, the victim of the crime he was accused of mistakenly identified him as her attacker. Wrongful convictions like these are not uncommon.

Leon Davis (left), the actual perpetrator of the crime for which Thomas Haynesworth (right) was sent to prison. (Virginia State Penitentiary)

Mistaken eyewitness identifications have contributed to approximately nearly 70% of the 368 wrongful convictions that have been overturned by DNA evidence in the U.S. Though eyewitnesses have traditionally been used to help identify perpetrators of crimes, there is growing proof that such testimony can be unreliable and influenced by poor practices used by law enforcement when assembling line ups, such as assembling a line up of photographs in which only one person matches the witness’ description of the perpetrator.

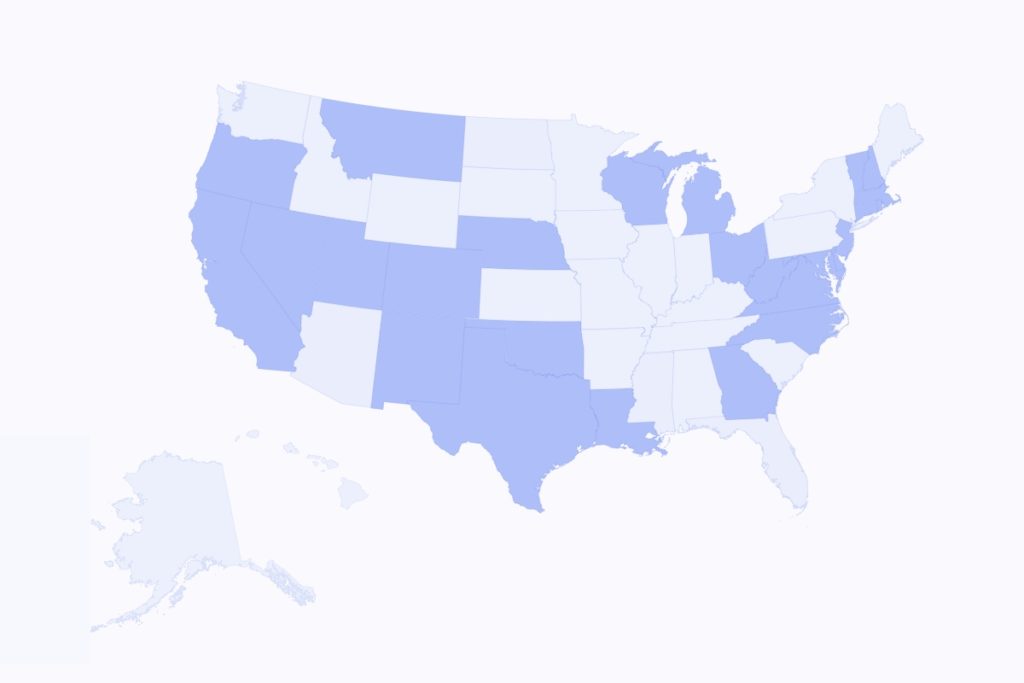

So far, 25 states have implemented reforms to help address this, like using “double-blind” line ups in which neither the administrator of the line up nor the eyewitness knows which person in the line up is the suspect.

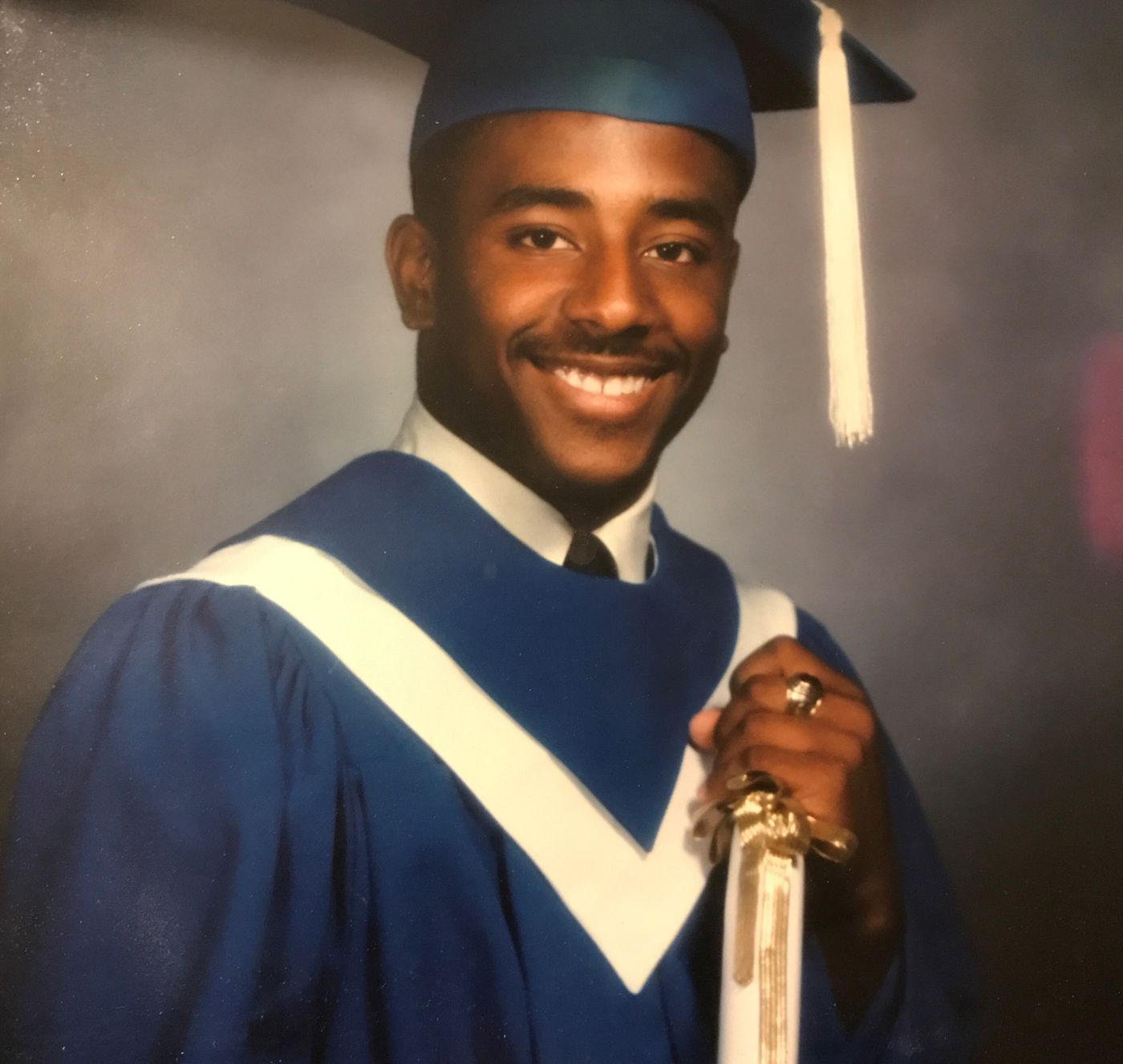

Chester Hollman’s high school graduation portrait. (Courtesy of the Hollman family)

Part Three — The Prosecution

Pennsylvania Innocence Project client Chester Hollman III was just 21 when the Philadelphia police pulled him over in the early morning hours of August 20, 1991. A 24-year-old graduate student had just been murdered nearby and Hollman’s vehicle fit the description of the car a witness had spotted leaving the scene. Hollman said he knew nothing about the crime, and maintained his innocence.

Though nothing other than the model of his car and a statement from Andre Dawkins — a man living with a substance use disorder and schizophrenia — tied Hollman to the crime, at that point, the police pursued him as a primary suspect. They were determined to close the case, whether or not they had the right person.

“The tactic that they used was just: Arrest, convict, move on to the next,” Hollman says in “The Innocence Files.”

“They were doing everything they could to close the case without trying to seek out the actual truth … I happened to be in the mix of it,” he said.

“They were doing everything they could to close the case without trying to seek out the actual truth. I happened to be in the mix of it.”

“They were doing everything they could to close the case without trying to seek out the actual truth. I happened to be in the mix of it.”

Chester Hollman Exonerated after 25 years of wrongful conviction

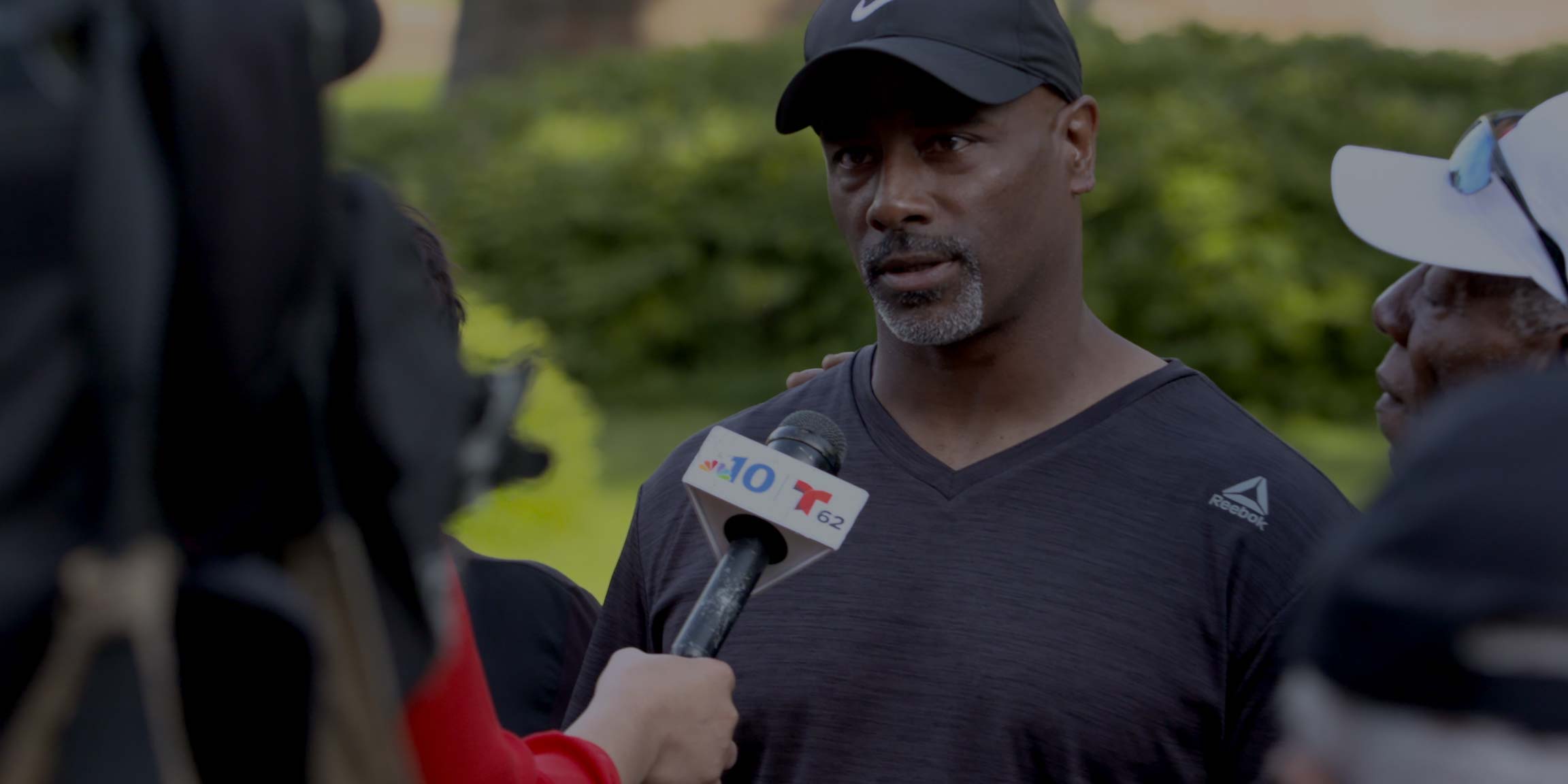

Chester Hollman after his release. (Courtesy of Netflix)

Hollman was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for a crime he did not commit. The police and prosecutorial misconduct ended up costing Hollman 28 years of his life. But Hollman is just one of three people featured in “The Innocence Files” whose case was fraught with misconduct.

Kenneth Wyniemko. (Courtesy of Netflix)

Kenneth Wyniemko says in the documentary that police officer Thomas Ostin called him his “million dollar man” when he arrested him because that’s how much money he would need to spend to get out of prison. Wyniemko was ultimately convicted of robbery and rape in 1994, though nothing seemed to point to him. He spent nearly a decade in prison in Michigan for a crime he didn’t commit due to prosecutorial misconduct in his case and the use of an unreliable jailhouse informant. He was exonerated with the help of the WMU-Cooley Innocence Project at the Thomas M. Cooley Law School and pro bono counsel Gail Pamukov.

More than half of the 2,588 people who have been exonerated since 1989 were convicted in cases involving some kind of official misconduct, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. And 185 people who were convicted in cases that used unreliable jailhouse informants have since been exonerated.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.