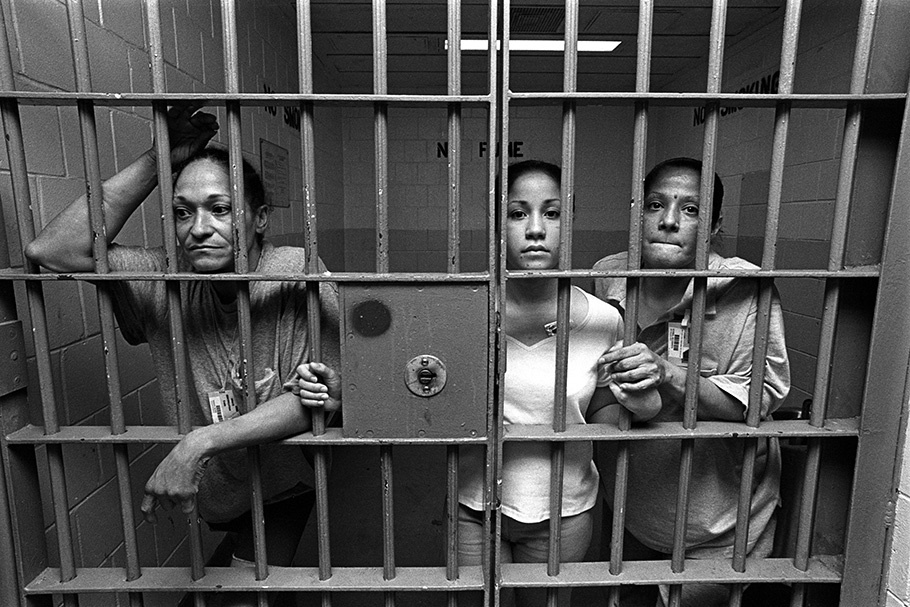

The power of teaching race and wrongful conviction to women in prison

04.06.16 By Alicia Maule

Innocence Project Digital Communications Manager, Alicia Maule, sat down with Edwin Grimsley, a Senior Case Analyst, to discuss his experience teaching a class at a women’s correction facility in New Jersey. For the last 9 years, Edwin has investigated hundreds of cases of innocence from people incarcerated as a member of our Intake & Evaluation department. He has also lead efforts on research in race and wrongful convictions, specifically on issues related to black youth, wrongful convictions and racial jury biases. Take a look at highlights from the conversation:

What was the call for you to go to Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for women?

I was brought on to talk about my research on race and wrongful conviction, specifically jury biases, to a class on “Race and Crime” taught by my friend Elizabeth Webster, a doctorate student at Rutgers University. The class is in the midst of reading Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson and a report by The Equal Justice Initiative from 2010 about illegal discrimination in jury selection, and discussing all-white juries, and what that means to the fairness of jury decisions.

What does your research say about women who are wrongfully convicted?

Wrongful convictions largely come from violent crimes, and men are far more likely to be convicted of violent crimes. Yet, according to research, in 63% of the cases of females exonerated, women were convicted of crimes that never even occurred. This probably factors into why women are less represented among the exonerated.

Black women—and women of color, generally—are underrepresented in wrongful convictions in comparison to black men who are overrepresented (they make up 61% of the DNA exonerations). According to Sentencing Project data, in 2010, Black women were three times more likely to be incarcerated than white women, yet we see a reverse in proven wrongful conviction cases, as white woman are twice as likely to be exonerated.

Are women of color not getting the resources they need to prove their innocence? What do you think can lend itself to that underrepresentation?

For non-DNA cases there’s a lack of resources in general. People of color, in general, lack the resources to fight their case.

Tell me about the women in the class—how did they react to your studies?

It was amazing because people who are close to prison have more vested interest in changing the system. When I was talking to them about racial biases, they were outraged, wanted change, and they came up with creative solutions to get around jury biases.

Most of my talk was about all-white jury biases; many research studies show they are extremely biased against black defendants. I read them excerpts from Calvin Johnson’s book Exit the Freedom, specifically about his jury process. They connected with it because they can hark back to their own trials—it’s real to them. You can really feel the power of the criminal system and what it means to people who are affected by it.

How often have you heard about a course on race and wrongful conviction in prison?

It depends on the prison system. It’s great for people. One woman in the class was talking about coming out soon and having enough credits to get her bachelor’s degree soon upon release. We’ve had exonerees who’ve come out with associate degrees and later a bachelor’s. It’s a real benefit to study in prison. Not all prisons and states have that. It’s rare to see a wrongful conviction class or talk about race and crime. I had to get pre-clearance on all the materials I brought. It’s powerful for people in prison to read other stories of others in prison. A lot of the students want to help others when they come out.

How did they react to you as an Innocence Project staff member?

It broke the ice immediately. They were amazed at the number of requests we receive (51,000 letters from 1993-2015) from people in prison and the kind of investigative and legal work that goes into getting someone out. It’s hard, even for us, to exonerate innocent people. The connection with our work—they really felt because they understood and knew other inmates who were innocent.

What motivates them to keep working on their cases?

This course motivated them and other courses and studies. Many of them are done with their appeals after years of fighting; they’ve accepted their sentences and convictions. I was impressed by how much they’re looking forward to the future—what jobs they are going to get and how they can help make the system better. Most of them were so positive.

What was a surprise that came out of the conversation?

How much they gained from reading Bryan Stevenson’s book Just Mercy, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, and the research studies on racial biases; they really wanted to learn more. They knew a lot about inequities in the system. I didn’t think they’d want to talk about it from a research and a solutions perspective.

From a numbers perspective, there are just more men in prison. Do they feel like people care about incarcerated women and that they’re listened to? Did they express any sentiment of being overshadowed by a male-dominated industry?

They wanted to talk more about gender and its intersection with race. It doesn’t get covered enough. Even in wrongful conviction work there isn’t enough work dedicated to women. The factors for women are more complicated, and there are gender biases that deserve exploration.

What’s next for you, Edwin, regarding women in prison?

This talk inspired me to think more about bringing gender issues into my race and wrongful conviction work. We all have to step outside of ourselves to understand biases and to think creatively. It’s powerful when we can hear about other people’s stories and provide solutions.

(Photo of Edwin Grimsley)

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.