This Man’s Lies Sent 4 People to Death Row and Dozens to Prison — Here’s What You Need to Know

12.16.19 By Daniele Selby

The New York Times Magazine and ProPublica recently published an astonishing story detailing the sometimes fatal consequences of one man’s decades of deceit and criminal behavior.

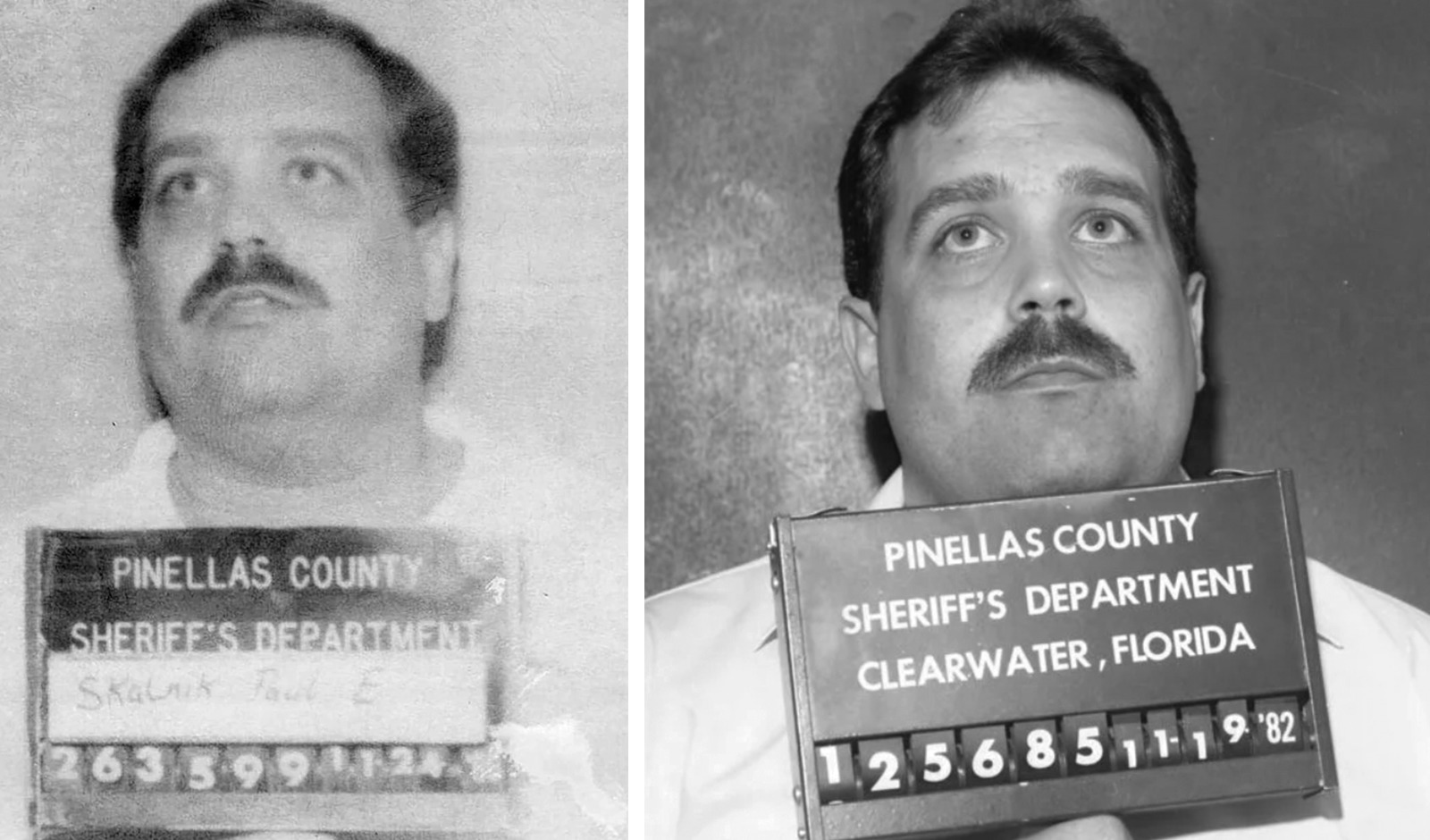

The man, Paul Skalnik, is responsible for testifying in dozens of cases leading to convictions or plea deals. And in four instances, his testimony helped send people to death row in Florida.

Jailhouse informant testimony is one of the leading contributing factors of wrongful convictions in the country.

James Dailey, who Skalnik claims confessed to him in 1986 while they were both held in Pinellas County Jail in Florida, was scheduled to be executed last month. Dailey, who maintains his innocence, was granted a limited stay of execution in October, but remains on death row.

In all these cases, Skalnik — who himself has a criminal record that includes charges of fraud, grand theft, and child sexual abuse — acted as a jailhouse informant. Over and over again, Skalnik claimed that men had directly confessed to committing serious crimes to him while in jail together, or alleged that he had overheard their admissions of guilt. Often, the men about whom Skalnik claimed to have intimate knowledge said they had never met him nor had any significant interaction with him.

Still, Skalnik would offer this information to prosecutors and law enforcement officials, who then put him on the witness stand, despite his history of fraud. Skalnik did so with the expectation that he would be rewarded with leniency or a reduction of his own sentence. And while those rewards were not always explicitly promised, Skalnik was rarely disappointed.

“This system circumvents the due process rights of the accused.”

Between 1981 and 1987, Skalnik provided information to officials or testified in at least 37 cases in Pinellas County, Florida, the New York Times reported. In exchange, Skalnik received such benefits as having a molestation charge dismissed and being granted parole halfway into a five-year sentence, even though the Department of Corrections deemed him to be at “high risk of further unlawful behavior.”

The practice of using, and rewarding, jailhouse informants is a well-established one. And Skalnik is far from the only person to have given unreliable testimony to improve his own circumstances.

Here’s everything you need to know about jailhouse informant testimony and how it harms our justice system.

Why is jailhouse informant testimony unreliable?

The use of jailhouse informant testimony in exchange for benefits, like those Skalnik received, creates a strong incentive for incarcerated people to lie. People may testify against a defendant with the understanding that they will later be rewarded, sometimes financially, but more typically through dismissed or reduced charges, special privileges while incarcerated, or with other forms of leniency within the criminal justice system. Because the incentive to lie is so great, jailhouse informant testimony is at risk of being unreliable.

Why don’t more people know about the incentives jailhouse informants can receive?

The jailhouse informant system is a largely secretive one, and people often lack understanding about how this incentivized system works. In some cases, jailhouse informants are not given explicit cooperation deals, so they can testify that they are not receiving any benefits in exchange for their testimony and cooperation. However, they may expect to be rewarded in the future.

“Benefits that are given to the informant in exchange for his or her testimony aren’t always delivered until after the trial in which he or she participates as an informant, and so those benefits aren’t always disclosed,” explains Rebecca Brown, Innocence Project director of policy. “This system circumvents the due process rights of the accused.”

How many people have been wrongfully convicted as a result of unreliable jailhouse informant testimony?

Jailhouse informant testimony is one of the leading contributing factors of wrongful convictions in the country. Since information about the rewards that jailhouse informants receive isn’t always recorded or easily accessible, the extent of their use can be difficult to track.

But the use of unreliable jailhouse informant testimony is the leading cause of wrongful convictions in cases where the death penalty is being considered, according to a study by Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions. Almost a quarter of people who have been exonerated while on death row were convicted by prosecutors who relied on a jailhouse informant.

Jailhouse informant testimony has also played a role in almost 20% of the 367 cases in which the accused was later exonerated by DNA evidence. More than 150 people who have been exonerated in the last three decades were falsely convicted in cases involving jailhouse informants, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

What can we do to reform the use of unreliable jailhouse informant testimony?

“A growing number of states are adopting safeguards to protect against false jailhouse witness testimony,” said Brown.

These safeguards include implementing pre-trial hearings for judges to screen out unreliable testimony and requiring prosecutors to track the use of jailhouse informants and the benefits they receive. Measures are also being adopted to ensure the defense receives prompt and complete information about these witnesses so they can be properly cross-examined.

“I would never be able to say on the stand that I believed the information he gave me was true and credible.”

“Anecdotally, we know that in those jurisdictions employing tracking systems, prosecutors often choose not to use them since their credibility is so questionable once these factors are assessed,” she explains.

After decades of providing testimony as a jailhouse informant, Skalnik’s luck ran out. He was arrested in 2015 for failing to register as a sex offender. He also had dozens of fake IDs and other faked documents in his possession. But this time, when Skalnik offered to provide “useful” information from inside jail, law enforcement turned him down.

“I would never be able to say on the stand that I believed the information he gave me was true and credible,” James Ferris, an investigator with the Panola County Sheriff’s Department, told the New York Times.

Still, Skalnik has largely managed to avoid serving substantial time, despite committing crimes that could carry a life sentence.

Several states are currently considering legislation to protect against the use of false jailhouse informant testimony.

If you live in Colorado, Kansas, Massachusetts, or Oklahoma, sign your name to support these reforms for a stronger justice system.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

September 10, 2020 at 4:12 pm

April 29, 2020 at 10:58 pm

This was a terrific series. I hope it reaches a huge audience. It’s a subject that gets way too little attention. Thank you for doing the enormous amount of work that goes into proving a person’s innocence. I only hope we can make the necessary changes in our tragically flawed criminal justice system. Hopefully this series will bring it to the forefront.

I wrote a chapter in my book about this crook. We were classmates at New Mexico Military Institute. The book is Special Crimes – Memoirs of a D.A. Investigator. He’s Chapter 5, The Scoundrel.