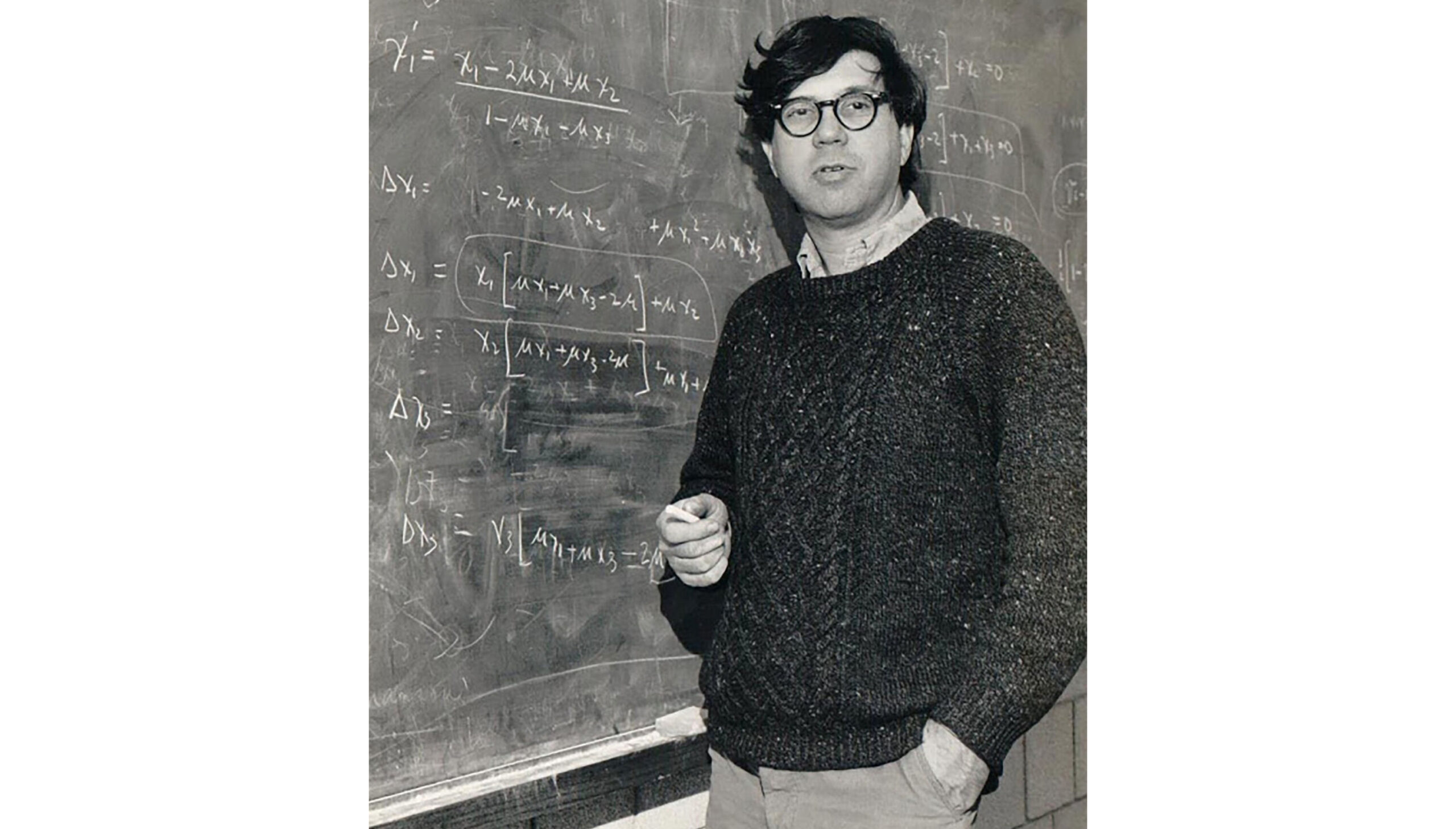

Remembering Dick Lewontin, Brilliant Biologist, Mathematician, Geneticist, and Mentor

Dick was for me, ultimately, a mentor on the meaning of a life well lived. I will miss him.

07.23.21 By Peter Neufeld

Richard (Dick) Lewontin died at his home in Cambridge, Mass., on July 4, 2021, at the age of 92. He was a biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and, for me and hundreds more, an incomparable mentor.

I met Dick in 1990, when he began mentoring Barry Scheck and me in genetics generally, and specifically population genetics and statistics to help us understand both the power and the limitations of this revolutionary DNA technology. As the years went by, we learned about so much more from him — the limitations of science, how science can be distorted for political purposes, and the primacy of one’s moral core.

When we met, Dick was the world’s premier thinker in the field of population genetics. Population genetics is a subspecialty of genetics which seeks to understand how and why genetic differences change over time within and between populations. In addition to his groundbreaking research, which, using DNA, debunked myths about racial variation and racial superiority, he was also a polymath and a Renaissance scholar. He wrote treatises in Italian, columns for the New York Review of Books on all matters of politics and human thought (frequently penned in a single draft), used 18th century opera as a metaphor for scientific discovery, helped run a music festival in southern Vermont, and served as a volunteer firefighter. When the architectural iconoclast, Buckminister Fuller developed the geodesic dome in the 1950’s, he relied on Dick’s math skills to determine for each size dome, the appropriate dimensions of the fabricating triangles.

He was a staunch and principled activist against the American war in Vietnam — a stance that caused him to resign from the prestigious National Academy of Science for their refusal to take a stand against the secret military research that led to the discovery of the toxic chemicals that the U.S. military used against the Vietnamese people and their countryside.

Barry and I first arrived at the outer chamber of this esteemed scientist’s lab, having just read of his countless accomplishments. And yet, upon welcoming two lawyers who were fundamentally illiterate in matters of science, Dick could not have been more genuinely kind, gracious, and obviously concerned about racism and economic disparities in our country. He was, in particular, concerned about the failings of our criminal legal system and wanted to help, even if helping meant taking time away from his other important obligations to educate two luddites. Dick did not shirk from this task.

Scientific impact on the innocence movement

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s — the early days of forensic DNA testing — only a few genetic markers (out of the thousands that had been identified) were used to create a partial profile of a piece of biological evidence recovered from a crime scene. This profile was compared to a reference profile from a person accused of committing the crime. If the profiles were different, the accused person would be excluded. If they were indistinguishable at the few genetic locations compared, they could be considered a “match” warranting further analysis. With the field of forensic DNA still emerging, we needed to understand the significance of such profiles being indistinguishable.

At the time, because so few markers were used, no profiles were truly unique. And without a scientifically valid estimate of how often a specific profile occurs in a population, a “match” is meaningless. For instance, a two-marker match could be as common as blue eyes and blond hair or as rare as a 7’2” albino. Two profiles could “match” either because they had the same source or due to coincidence. But, if a profile could be shown to occur very rarely in a population, then the “match” would be a much more likely indication that the crime scene evidence had come from a suspect.

In our search for a valid method for estimating the rareness of a DNA profile in a population, Barry and I were led to Dick.

At first, we’d meet in his inner office where piles of books and pictures would be laid out on the floor where we sat. Dick would stand and walk from pile to pile, picking up texts, illustrations, and graphs. Step by step, he took us through the history of our collective knowledge of human evolution up to his paradigm-shifting discovery about the degree of genetic diversity among humans (and, for that matter, among all species).

Prior to Dick’s work in the early 1970’s, policy makers and scientists believed Asians, Africans, and Caucasians had been isolated from each other for so long, that they must have developed many different genetic mutations that generally distinguished one “race” from another. These misconceptions fueled many radicalized and racist views of the world’s populations and became the “go to” myth to “explain” disparities in education, housing, health, and wealth for decades.

But Dick’s work, interpreting vast quantities of data, and his brilliance in genetics and mathematics brought him to a different conclusion — on the basic genetic level, so-called “racial” and “ethnic” groups are remarkably similar. And his conclusion has been further corroborated by other scientists repeatedly over the last four decades.

Despite superficial differences like skin pigment, facial features, and hair texture, there is much greater variation among people of shared ancestry than between populations of differing ancestry. In fact, roughly 85% of human genetic variability occurs within populations in which people have shared ancestry, while only 7% of variation distinguishes these populations from one another. Ultimately, Dick explained, for our forensic purposes, there was a dearth of data at the time and that a scientifically valid estimate of the frequency of any forensic DNA profile could not yet be assigned.

Dick became our lead witness at an admissibility hearing in 1990. Barry and I had never encountered an expert witness with greater focus and a natural ability to create on the spot metaphors especially designed for the individual judge to explain complicated scientific and statistical principles. During the prosecutor’s cross-examination, Dick never looked at the questioner, instead maintaining his gaze and conversation with the judge.

As we all know, politics often intrudes into judicial decision-making. The federal magistrate ruled for the government. Had he not, it would have set back the FBI’s DNA lab for at least a decade. Notwithstanding the magistrate’s decision, when the National Academies of Sciences (NAS) report establishing reliable practices for forensic DNA typing was published in 1992 — the same year the Innocence Project was founded — the scientists accepted most of Dick’s criticisms of the FBI’s separate databases for “African Americans,” “Caucasians,” and “Hispanics.”. The FBI was so alarmed by this unexpected development that, two years later, at their urging, a second NAS report was issued and offered a roadmap for estimating population frequencies for forensic DNA profiles, much more to their liking. Dick’s work in those early days and his critiques of the emerging forensic DNA field, helped shape DNA testing and impacted thinking about “race” as a biological construct, for future generations.

After our first few classes with Dick, our meetings moved to a more public room in his lab — we sat at an old conference table presided over by a stuffed moose head, evidently a throwaway from the zoology museum next door. Students, as well as famous scientists from all over the world, would wander in and out. The conversation would temporarily move away from criminal justice to his scientific critiques of sexism, the myopia of biological determinism, and the misuse of the label “genius.” Dick believed that there are no geniuses, only works of genius, and provided a number of examples and funny anecdotes of Nobel prize winners, revolutionary leaders, and inventors touted as geniuses, but who were, in other aspects of their lives, “dummies.”

Dick always believed in the utility of the Innocence Project. In addition to making financial contributions, he constantly urged us to expand our work. He reminded us that with the compelling voices of our exonerees, we could bring attention to wrongful conviction and achieve victories in social justice long denied to others.

For two decades, I continued to visit Dick and his life partner, Mary Jane, whenever I was in Boston for work. Our encounters ceased about 10 years ago when he explained to me that his own cognition was slipping. But his impact on the field of forensic DNA, the innocence movement, and myself are still deeply felt. He was for me, ultimately, a mentor on the meaning of a life well lived. I will miss him.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.