Black History Month: Different Lives; Shared Vision

02.27.15

By Robyn Trent Jefferson and Rebecca Brown

In recognition of Black History Month in February, the Innocence Blog will feature a nearly month-long series that will examine the intersection of the nation’s evolving criminal justice system, especially around wrongful convictions, and the lives of black people in 21st Century America. The series will feature personal and professional stories and perspectives by legal and law enforcement experts, as well as people at the forefront of changing post-conviction laws for the wrongfully convicted in the United States. Please visit the Innocence Blog this month to read guest posts from all the contributing authors.

As colleagues at the Innocence Project, we both work towards a common goal of preventing miscarriages of justice, often along racial lines. While we have often had some shared observations, we have not always had shared experiences even though, as we soon realized, we both attended—albeit at different times—the same public schools in Montclair, New Jersey. Hailed for diversity and racial balance in its school system, this suburban enclave has also come under fire over the years for touting its integrated schools while maintaining segregated classrooms. After all, the courts only first imposed desegregation in 1968.

As two children who lived in Montclair, race was always a central part of our existence, prompting discussions about whether living there influenced our desire to work at the Innocence Project.

Robyn:

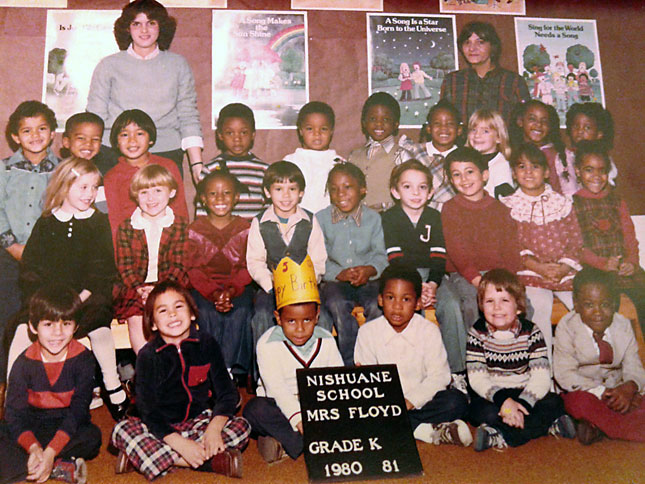

Robyn’s Kindergarten class

Pride is what I first think about when I reflect on my journey through the Montclair Public Schools system. As a black child, I was proud that I was following the path of family members and, in fact, had some of the same teachers that taught my parents at Montclair High School.

From my youth, I can recall advocating for what was right, often being the referee between classmates, siblings and neighborhood friends in settling disputes. In middle school, as my interest in the justice system grew, I began to notice that consequences for “bad” behavior in school differed greatly, depending on the race of the actor. By the time I got to high school, these differences were clearly marked.

As we grew older, some of the “disputes” became more serious, oftentimes, resulting in public humiliation and a likely dance with the legal system, a financial burden for many poor families, many of which were black.

Although we were 15 years apart, during both mine and Rebecca’s tenures, the district faced many of the same issues that it had been cycling through since its inception. Transformations from neighborhood schools to busing to magnet schools were the root of almost continuous disharmony in the district some called “Integration Eden.” Sadly, the disparate treatment in the schools continues today. These [negative] transformations have only served to inspire me in my work and overall mission to eradicate racial inequity.

Rebecca:

Rebecca’s Kindergarten class

I began attending Montclair public schools in 1979 as a white four-year-old. My clipped memories of the early days seemed happy enough. I had the fortune of experiencing (or misremembering?) the integrated classroom. But I also share with Robyn memories of disparate treatment along racial lines, which grew starker as I grew older. When I was very young, it was less palpable. It was something I just felt but couldn’t describe—seemingly shorter tempers for non-white kids’ misbehavior and overheard stories of a police presence in only some corners of the community.

By the time I was in high school, I had moved to New York City and friends from early childhood and my new New York friends were suddenly coming into contact with the criminal justice system for the first time. Shoving matches were now labeled assaults. Normal teen angst became disorderly conduct. And rarely were my white friends getting picked up on either side of the Hudson River.

The dissimilar treatment of my black friends suddenly became more pronounced and observable. I believe my time in Montclair helped to sensitize me to these disparities but I am also painfully aware that observing these differences is very different from living them. It is why I deeply reject any assertions that we live in a “post-racial” society. In the same way that an “integrated” school inevitably exposes and reflects an unaddressed legacy of discrimination, so, too, does the American criminal justice system.

___________________

For both of us, racial integration defined our early lives. While we benefited from diverse classrooms, we were also privy to early observations of the disparate treatment our classmates received. As we grew past our elementary school days, we would see that painful incongruence repeated in many institutions and settings, perhaps most obviously in the criminal justice system

In a sense, we carry both the triumphs of the civil rights era as well as the goals that are yet to be realized. Truly a bitter and sweet load, our friendship and shared work is a testament to the fact that the dream of racial justice is a collective one, and one that we hope can be realized more fully together.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here. Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.